If we want to find life on Saturn's moon Enceladus, we need to rule out Earthly hitchhikers

The icy moon's promise is also its vulnerability.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Want to find life in an exotic corner of the solar system like Saturn's icy moon Enceladus? First, you have to make sure you don't get all excited about a detection only to realize you've just discovered hitchhiking germs from Earth.

To avoid that letdown, planetary scientists think carefully about how to avoid contaminating any instruments designed to look for traces of life on other worlds or moons.

That's true even of missions that will likely never fly.

So when Shannon MacKenzie, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, and her colleagues began work on a mission concept study for a life-detection mission to Enceladus, they knew they needed to be careful about what their hypothetical spacecraft was bringing from Earth in order to make the project realistic. The study was one of three arranged to give an independent report that sets priorities for NASA a concrete sense of what sort of science an outer solar system-bound spacecraft could do with a few billion dollars.

Related: Photos: Enceladus, Saturn's cold, bright moon

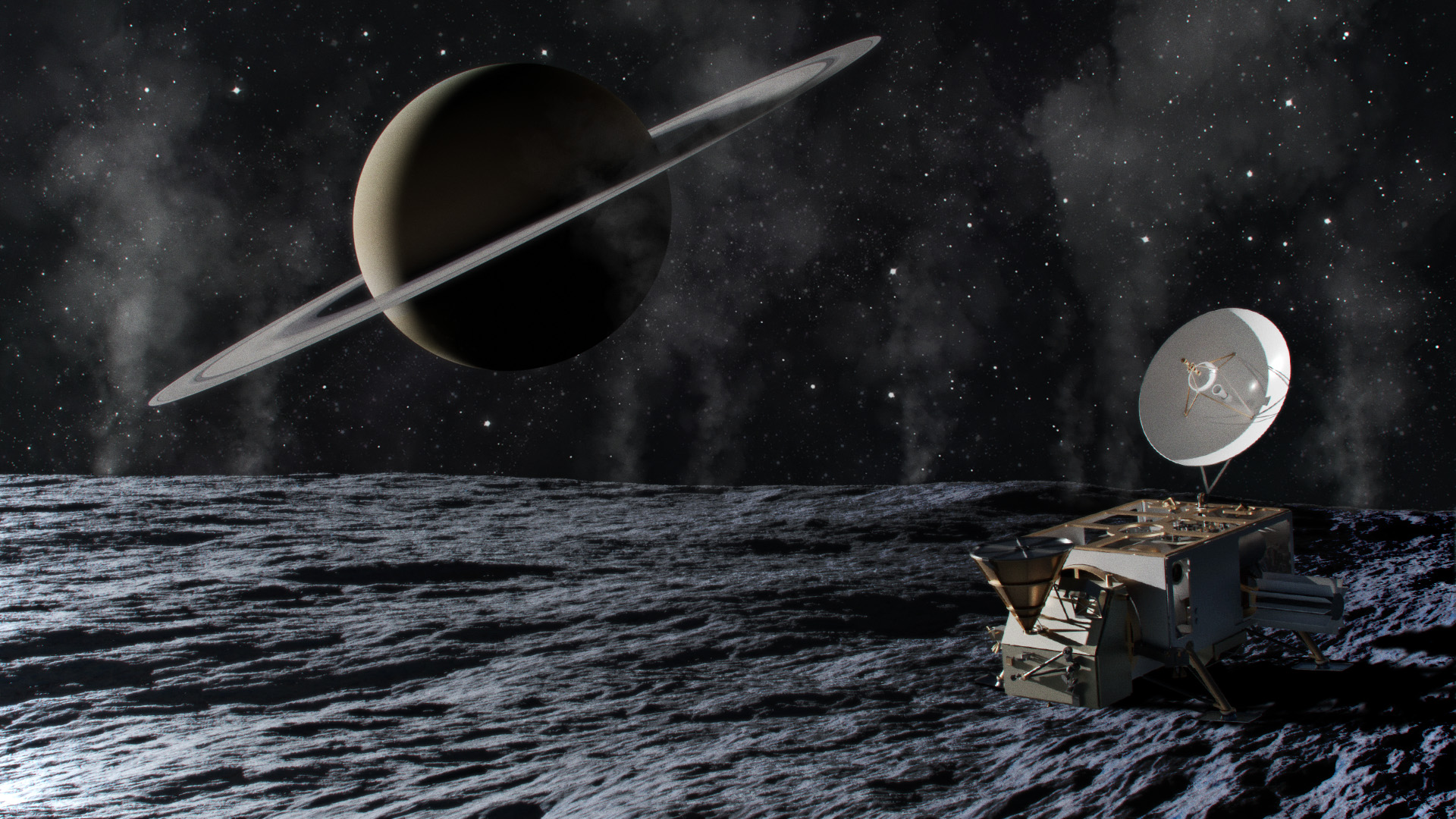

MacKenzie led the team that designed a mission concept nicknamed Enceladus Orbilander, a single spacecraft that could first orbit Saturn's moon, then land on its icy shell, all while looking for signs of life. During both mission phases, the team needed to consider the guidelines of planetary protection, which are meant to reduce the possibility of a spacecraft going to a habitable environment and seeding terrestrial life there.

To meet those guidelines, MacKenzie told Space.com, the team needed to think through three aspects of the spacecraft's operations: how to maintain a safe altitude during the orbital phase; how to avoid crash-landing at a delicate spot on the icy crust; and what would happen to the spacecraft after it finished its mission.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

An ocean under ice

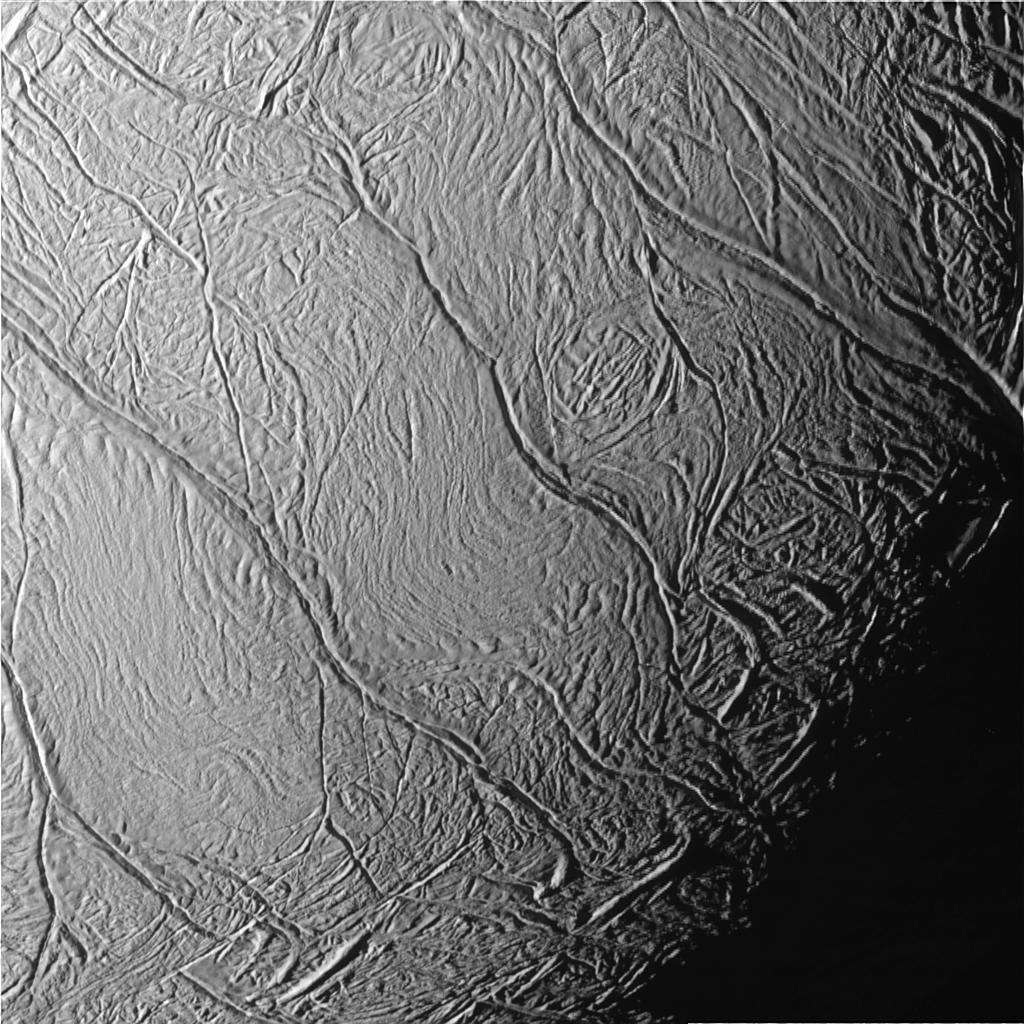

Enceladus' vulnerability, and promise, is its subsurface ocean, which vents out into space through plumes in the moon's southern hemisphere. That ocean is home to organic chemistry, water and energy, the three components that scientists have identified as crucial for life. But throw some terrestrial bugs in that ocean and they could flourish — astrobiologists' nightmare scenario. So whether you're in orbit or on the surface, it's crucial to ensure that the spacecraft stays away from that ocean, MacKenzie said.

"For an orbiter, you want to make sure that you don't accidentally impact the surface at a high velocity and somehow contaminate the ocean," MacKenzie said. "When you are a lander, you don't want to botch the landing and do the same thing."

Then, there's the matter of the mission's ending.

Planetary protection concerns sent the Saturn's last visitor, NASA's Cassini spacecraft, plunging into the planet's atmosphere to melt in its clouds lest the probe contaminate Enceladus or another potentially habitable world. Orbilander's finale would be less dramatic: Since the mission would eventually land on Enceladus, it eliminates the need to deal with an orbiting spacecraft's potential wandering.

But planetary protection does increase the stakes when choosing a landing site. In addition to ensuring that the landing site hosts compelling science data and is safe for the touchdown itself, the team also needs to ensure that the spacecraft could stay there indefinitely without ever coming into contact with the subsurface ocean. That would allow the spacecraft to die in place with no additional planetary protection work necessary.

"We want to make sure that we're not landing in too warm of an area, so we aren't landing directly on the tiger stripes, for example," MacKenzie said, referencing the parallel faults that scar the southern polar region of Enceladus. "Landing in areas where the surface is not as fluffy, like not snowpack, and colder should ensure that we won't melt through."

Fighting contamination

For a mission aspiring to detect signs of life, the bar is a little higher than simply not spreading terrestrial biology to another world. The team also needs to be confident that intriguing detections at Enceladus are actually from Enceladus, not a signal of terrestrial life that came along for the ride.

A key piece of meeting that goal is keeping the spacecraft as clean as possible before launch. But no matter how careful a mission team is, some biological material will make it through.

"You can never get perfectly clean," MacKenzie said. "So doing the best that you can keep clean and then characterizing what contaminants are there makes the results more robust."

MacKenzie and the rest of the Orbilander team also built in a second way to increase their confidence in potential detections of life at Enceladus: plan for the instruments to test themselves, including, for example, with blank samples.

But those techniques are ready to go to the icy moon, she said, and the moon is ready for them. "I think it's a really exciting time to be doing life detection," MacKenzie said. "We have such a good standing on which to ask these kinds of questions at Enceladus."

That's true even though there's no single instrument that scientists can send on Orbilander or any other spacecraft to crack the mysteries of astrobiology, MacKenzie said.

"There's no one life-detection instrument, where you just press a button and then it's, 'Oh, there's life here' or 'Oh, there's not life here,'" she added. "That would be awesome but that doesn't exist. Instead, we have to come up with a couple of different avenues to provide enough evidence to convince ourselves."

The life-detection rationales built into the Orbilander concept rely on six instruments. Although one may be a rush to prepare for a late-2030s launch, the spacecraft should be able to recognize life — if there is life to recognize — without it, MacKenzie.

"This mission is ready, we're ready to do this," MacKenzie said. "We don't need to wait on any kind of magic bullet."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.