For NASA's DART asteroid impactor mission, success will come down to the last 60 minutes

The moonlet the asteroid wants to move will only be visible in its sensors an hour before impact.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Following years of preparation, NASA's asteroid impact mission will have just an hour to finalize its path after seeing its target for the first time, engineers told reporters in a news conference on Sunday (Nov. 21).

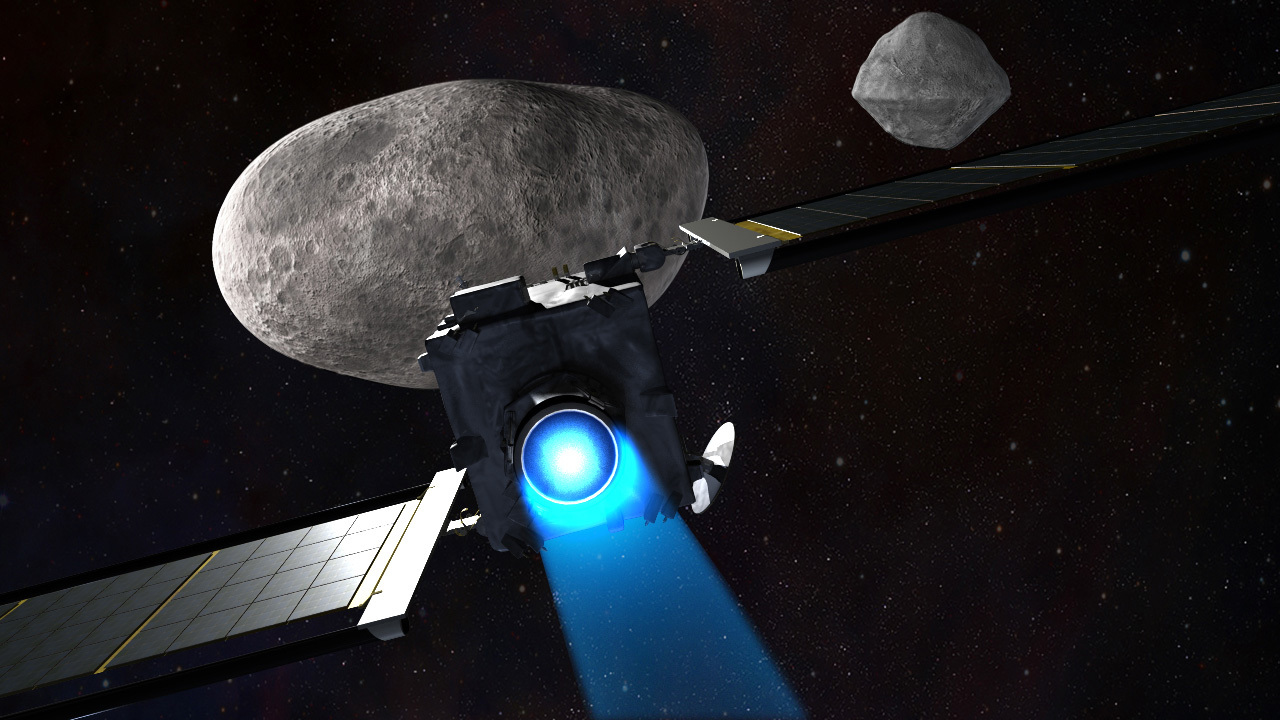

That mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), is scheduled to launch no earlier than 1:20 a.m. EST (0620 GMT) on Wednesday, Nov. 24 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

Should all go to plan, the mission will end in fall 2022 with a dramatic impact on an asteroid moonlet. While DART program scientist Tom Statler told reporters the mission is "fairly simple," in that it carries only one instrument, he acknowledged that the instrument will have a lot to do in its last hour before impact.

Related: NASA's DART will smash into an asteroid, but don't worry. Earth isn't at risk.

DART is an attempt to practice planetary defense technologies before we need to use them for real. Decades of scanning the sky have produced no known threats to Earth, but NASA says it wants to further progress the most mature technology to protect our planet, which is called a kinetic impactor.

The plan calls to slightly shorten the orbit of the moonlet Dimorphos around its parent asteroid, Didymos. NASA and numerous planetary scientists have told Space.com that there is no way the asteroid's path, which is harmless to us now, will be altered to pose a threat to Earth.

DART will carry a single instrument called DRACO, which stands for Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation. DRACO will image Dimorphos and navigate to its target.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the last hour before impact, DRACO will need to begin navigating the spacecraft to Dimorphos when the moonlet is just 1.4 pixels wide in the field of view, Betsy Congdon, DART mechanical systems engineer, said in the same news conference.

Happily, more maneuvers will be possible in the final minutes before impact; by mission end, images should be able to show us the surface at a resolution better than 8 inches (20 centimeters) per pixel, according to NASA. This precision will also improve the spacecraft's ability to navigate; for example, by two minutes out, scientists will precisely know the shape of the asteroid moonlet.

But Congdon said the engineers are well aware of the complexity facing them, not least after years of simulations to get ready. "I mean, it is really hard, right?" acknowledged Congdon, who is with the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). "We have not actually navigated into another body before. So that is really challenging."

Another large constraint on the mission will be time, as Statler noted the mission will be over in only 10 months. By comparison, the 12-year Lucy asteroid mission to visit numerous solar system asteroids (which launched Oct. 16) will still be preparing for its first celestial encounter. "We'll be done before we even get to Lucy's first destination," said Statler, who is with NASA's planetary science division.

Then there is the force of the impact itself. The engineers know how fast the spacecraft will be moving (15,000 mph or 24,000 km/h) and how massive the spacecraft will be when it slams into Dimorphos (1,234 pounds or 560 kilograms), but a big question is how much of the momentum will transfer to the moonlet.

"A lot of this will depend on the nature of Dimorphos itself," Andy Rivkin, DART investigation team lead at APL, told reporters. From ground-based telescopes, he explained, it's impossible to see whether the moon is a loosely held together "rubble pile" or something more solid.

If it's more like rubble, he explained, DART is not expected to make a large push as the space between the rocks would act as a bit of a cushion. But it could have a larger effect on a more solid object. He estimated a more solid object could have perhaps a factor of two or a factor of four more push than something less so.

The hope is the change in orbit, estimated at just a fraction of a millimeter per second, will be visible from ground-based telescopes and from an Italian CubeSat (LICIACube) that will ride to the asteroid with DART. But if not, there is a backup option on the way. The European Space Agency plans to launch a spacecraft called Hera to arrive at the asteroid in 2026 or 2027, after launching in October 2024.

While the focus on the mission is of asteroid defense, getting a glimpse of yet another small world will allow scientists to also continue building their understanding of how our solar system evolved, noted Lori Glaze, director of NASA's planetary science division. Our solar system used to be mainly made up of asteroids and comets billions of years ago before most of them coalesced into the planets and moons we have today.

"The DART science mission, with NASA's other asteroid missions, is helping to shape the planetary science community's understanding of our solar system and asteroids and comets," she said. In particular, DART will shed more light on Didymos' and Dimorphos' physical properties from up close, she said, which in turn can be extrapolated to the thousands of other asteroids we haven't yet visited.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.