Spring skywatching: Big Dipper and a 'big' little moon reign in the night sky this month

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

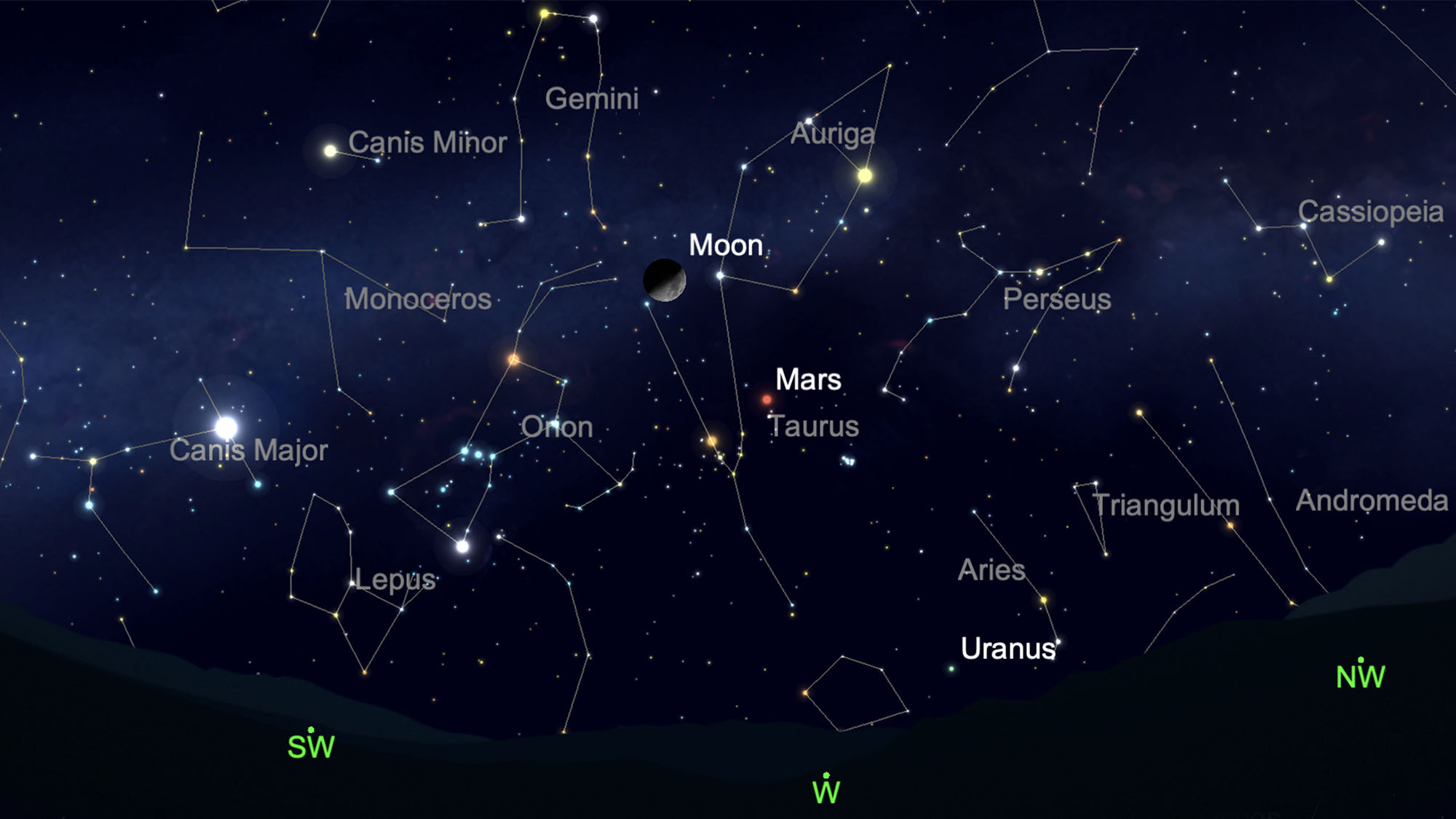

March evenings tend to offer more moderate temperatures for those wishing to observe the winter constellations in relative comfort.

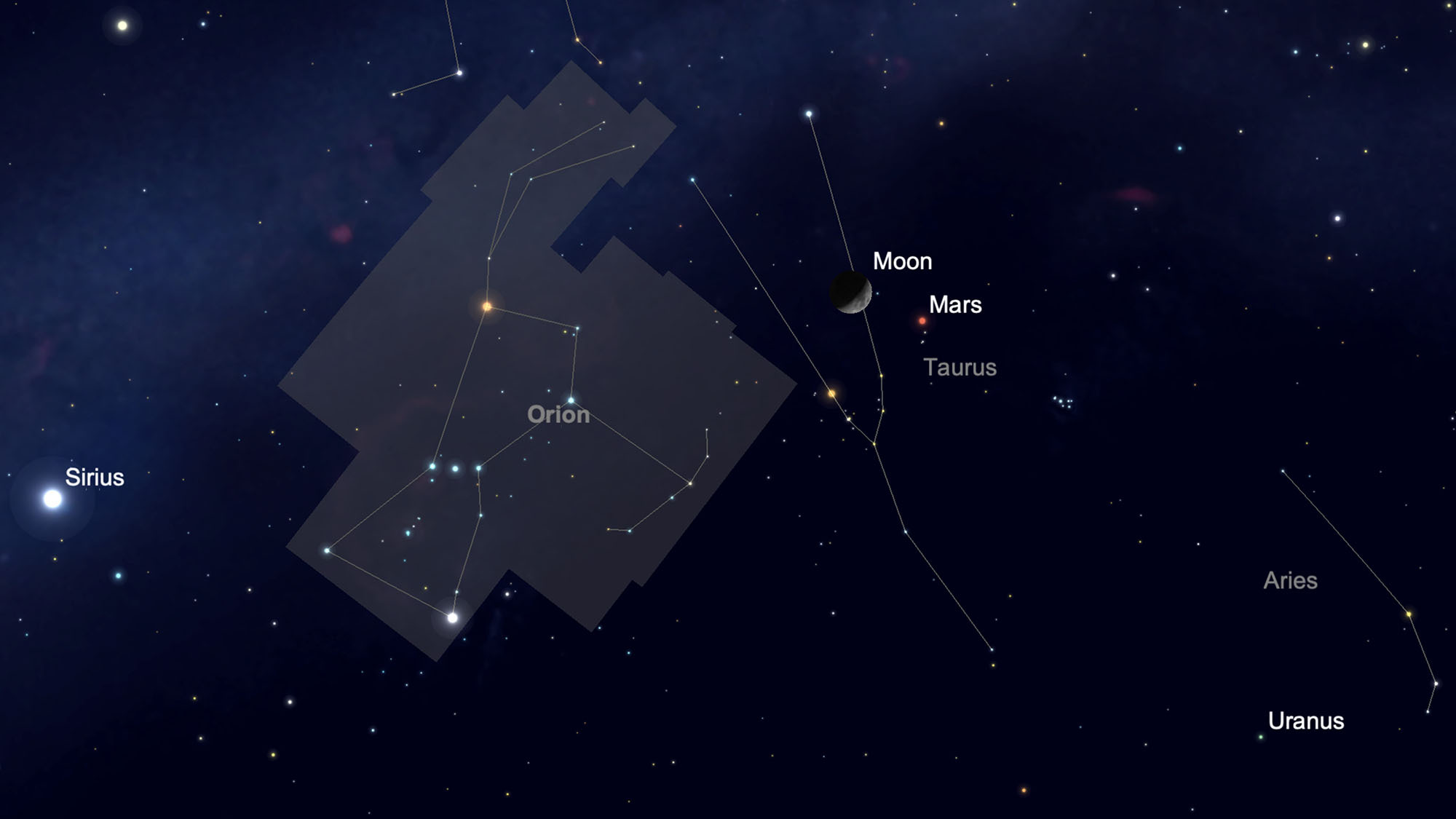

During the latter half of this month, Orion, the hunter and his dazzling entourage have moved into the western half of the sky by around 9 p.m. local daylight time, yet they are all still very well situated.

To those who did not head outside to spend time outdoors with the "mighty hunter" and his retinue during January and February because it was simply too cold, the next few weeks should offer more pleasant observing conditions.

Related: Best night sky events of March 2021 (stargazing maps)

The emergence of the "big bear"

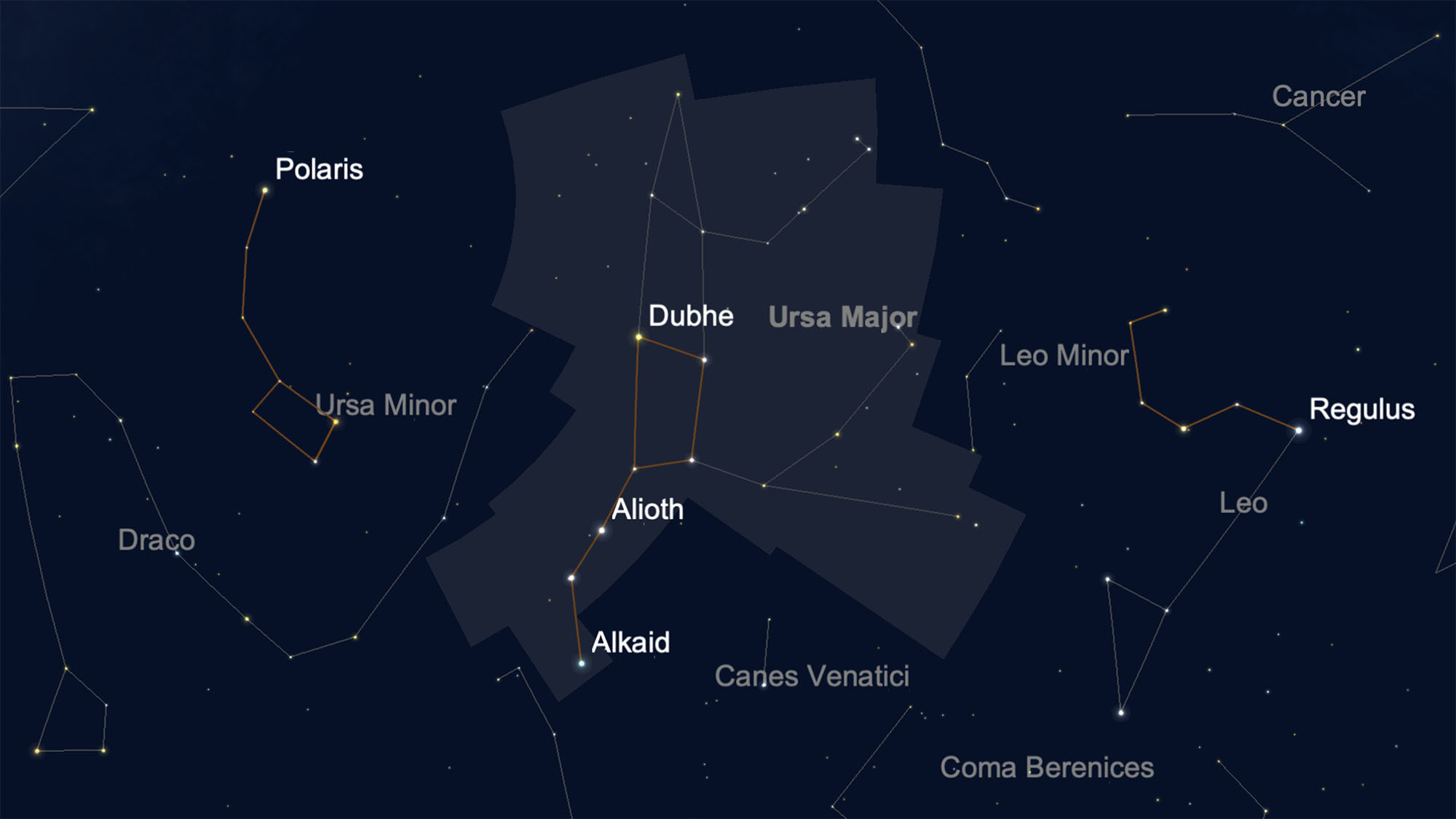

As we begin to lose Orion and company for another season, we regain the Big Dipper as a prominent evening asterism, or star pattern, now soaring high in the northeast. Not a constellation in of itself, the Dipper simply happens to be the most conspicuous part of the constellation Ursa Major, the great bear, which is generally regarded as a spring constellation in the Northern Hemisphere.

In this regard, that certainly makes sense. Most bears go into hibernation by mid-December, when the weather grows cold and the food supply finally dries up. That is when they will retreat to their winter dens. If you look for Ursa major in the night sky right after sunset at that time of year, you'll find most of that constellation — save for the Big Dipper — situated below the northern horizon.

But by mid and late March, male bears begin to emerge and prowl around and so it is with our celestial bear: At nightfall we can find Ursa Major well up in the northeast. And by the beginning of May, our Big Bear can be found directly overhead as darkness falls.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For skywatchers in the Southern Hemisphere, Ursa Major is best seen from the northern latitudes in the autumn months of March through June (when it is springtime in the Northern Hemisphere). From the more southerly parts of the Southern Hemisphere the constellation remains beneath the horizon all year long.

Incidentally, the Big Dipper itself is often called circumpolar — that is, it never rises or sets; it's always above the northern horizon. Yet, its most southerly star Alkaid passes just above the northern horizon only for observers north of 40 degrees 33 minutes north latitude, since its declination is 49 degrees 27 minutes. For those living in New York City, Alkaid barely skims above the horizon at its lowest point. But if you live in Philadelphia, Alkaid briefly drops out of sight below the north-northwest horizon for about an hour before popping back up into view in the north-northeast.

A deceptively big moon

When you look at the Big Dipper high in the sky, check out an incredible "moon illusion," which was first pointed out to me by the late popularizer of stars and constellations, George Lovi. Personally, I think Mr. Lovi's moon illusion is even more striking than the classic horizon version which makes the moon appear overly large as it rises or sets.

Try to imagine more than 10 full moons lined up between the Dipper's "Pointer Stars" (Dubhe and Merak). They are a little less than 5.5 degrees apart and the moon itself measures about 0.5 degrees, so there's ample room. But how to convince oneself of this by looking at the Dipper in the sky? Certainly, four moons would fit, maybe five, but 10?

The fact is that when comparing the moon's recollected size with distances between stars in another part of the sky, it is never imagined as only 0.5 degrees across, since for most people it seems to appear at least a degree — or twice as large — as it really is.

This is why it is not advisable to use the moon to measure-off angular distances in the night sky. Last summer, for example, when Comet NEOWISE attracted widespread attention, its tail spanned 10 degrees. Some may have gotten the impression that this implied that — mentally — this comet's appendage would appear as long as 20 full moons spaced from end to end.

Yet, in the sky, for many, the tail likely appeared only half as long!

And here at Space.com, whenever the moon closely approaches a bright star or planet, we always alert prospective observers that both celestial bodies appear closer than what is forecast because of the abnormally large size of the moon. That was the case last October when the moon passed very close to Mars.

Even in the planetarium!

And this remarkable illusion is not just confined to the real sky, but the "pretend universe" of the planetarium as well. When the first such projector was designed by Zeiss (in 1923) and was made to project moon and sun images extending over a 0.5-degree arc on the dome as they appear in the real sky, it was found that they appeared ridiculously too small to be realistic although they were in actuality the correct angular size. And ever since, all planetarium projectors, manufactured in different countries, including here in the United States, always show the moon and the sun twice as large than in the actual sky.

But, nearly a century ago, it must have been a bitter pill to swallow for the Zeiss engineers at Jena, Germany, who always prided themselves on the pinpoint accuracy of their work. Yet here was one of the very few places where accuracy had to be sacrificed for the sake of realism!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.