Astronaut requirements changing rapidly with private spaceflyers, long-duration missions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Being an astronaut of the 2020s will be completely different than it was for any astronaut that came before, a panel of spaceflyers told the virtual International Astronautical Congress Wednesday (Oct. 14).

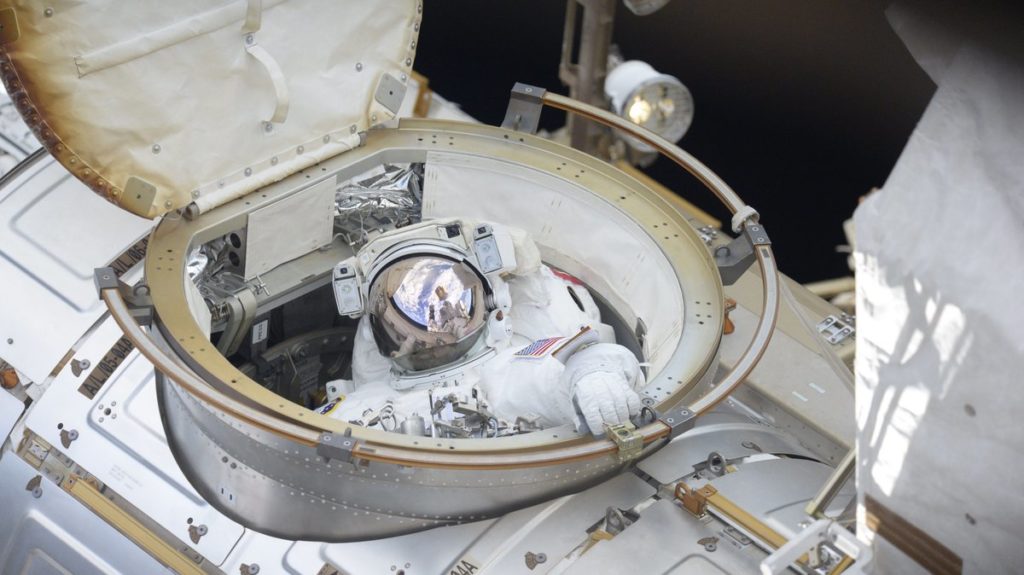

The spaceflight environment is rapidly changing due to several different factors. The International Space Station (ISS) is pushing harder into commercialization and will soon be welcoming more and larger space agency crews on commercial crew vehicles while bringing in a few private astronauts.

Meanwhile, NASA and its international partners are preparing for the next phase of human spaceflight missions after the ISS, which they hope will include moon landings in 2024 and eventual astronaut excursions to Mars. Also in the next few years, private companies such as Virgin Galactic hope to send paying astronauts on suborbital flights, in a bid to open up space to more people besides professional astronauts.

Related: How commercializing the International Space Station can help astronauts get to the moon and Mars

This is all quite a different environment from when the ISS housed the first long-duration crew in October 2000, which was 20 years ago this month. The demands of astronauts are quickly changing and evolving as the science progresses, even between missions, former NASA astronaut Cady Coleman said.

"It was very exciting to see [NASA astronaut] Kate Rubins' launch with her Russian crew eight hours ago," Coleman said, referring to the launch of Expedition 64 earlier Wednesday (Oct. 14) from Baikonur, Kazakhstan towards the International Space Station.

Rubins is best known for being the first astronaut to sequence DNA in space, and she will be pushing the science even further since her last excursion in 2016. Coleman said during Rubins' last mission, Rubins grew heart muscle cells, and you could see the cells beating under a microscope. In this mission, Rubins and the team of scientists on Earth will grow small pieces of tissue with strain gauges to see what happens to the heart muscle when it's in space, Coleman added.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It makes me think of kind of what's really happened in 20 years on the space station, in science," said Coleman, who flew two space shuttle missions and the long-duration Expedition 27 mission. On one of her shuttle missions, STS-73, she said it was "a preparation for how we [were] going to do science experiments on that space station. How would the scientist see their data? What's practical? What's not practical? What can astronauts do? What can scientists do? I'm very proud of that work."

It's not only the science that has changed; it is also the skill set of astronauts. The first generation of astronauts that tested out orbital missions and moon landings in the 1960s were largely drawn from military test pilots, while scientist-astronauts began participating in Apollo, Skylab and space shuttle missions in the 1970s and 1980s. Since then, we have mostly seen scientists and military-trained astronauts in space, although the requirements continued to change over the decades.

Two-time European Space Agency spaceflyer Pedro Duque, who visited the ISS in 1998 and 2003, said that during his busy years training as an astronaut, he found it hard to imagine being anywhere else. But in 2018, he became the Minister of Science, Innovation and Universities for the Spanish government and said his astronaut skills are still helping him every day in this position.

"I believe that by working as an astronaut you learn, and that is useful for many things in life," he said. "You learn to work with very intelligent people and let them do their job while you do yours. You understand how you can be in a position that people listen to you, but then you will learn how to use this wisely — or not. And [you] try to lead by example, and by conviction, and this is something that I have tried to use in my whole life, in all the positions have been."

NASA astronaut Ricky Arnold flew a space shuttle mission and the long-duration Expedition 55 mission in 2009 and 2018, respectively. It was an era when training in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) became especially important as astronauts learned more generic "expeditionary behavior" for long-duration missions, he said, rather than focusing on a few small specific skills.

The newer shift in astronaut training, he added, is getting ready for the proliferation of new spacecraft — including SpaceX's Crew Dragon, Boeing's Starliner and NASA's Orion spacecraft. This will add on to the Russian Soyuz spacecraft that currently ferries astronauts to space. "There is the potential for four different vehicles you have to figure out how to fly," Arnold said, "and it'll be interesting to see what the training team does with the next class of astronauts that will come on."

Related: More than 12,000 apply to become an astronaut for NASA's 'Artemis Generation'

The skillset will change even further when private astronauts come on board the ISS or work on other spacecraft, said Michael López-Alegría, who flew three space shuttle missions and the long-duration Expedition 14 in the 1990s and 2000s.

López-Alegría flew previously with spaceflight participant Anousheh Ansari and said he was impressed with her skillset in blogging, a new idea when they went to space together on a Soyuz in 2006. More new ideas will be forthcoming as different types of people make it to space, he added.

"We're entering a new realm where you don't have to be a professional astronaut to fly to space; it's the era of democratizing that access," López-Alegría said. "It's very difficult right now, because the seats are few. And as a result, they're quite expensive to go. But I'm quite confident that these prices will come down, just like [for aviation] in the 1920s and 1930s. Commercial aviation was only something that was reachable by the very, very wealthy."

While López-Alegría is retired from NASA, he's going back to the space station in another format. He joined Axiom Space as director of business development in 2017, working with a company that is building a private module for the space station as it dreams of creating independent space stations in the near future. López-Alegría will be making a return to the ISS on an Axiom Crew Dragon mission in 2021, according to Space.com partner collectSPACE.

When pressed about who else will be on that mission during the panel discussion, though, López-Alegría said he "cannot really confirm or deny what's happening." But he did say Axiom plans to fly a private mission in the fourth quarter of 2021, providing the company passes approvals with its contracts. "Until such time, we're not ready to discuss who the other crew members will be. But I can tell you it's going to be the first public-private commercial mission," he added.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.