Why Smashing Asteroids to Save Earth Likely Won't Work

If humanity ever truly felt our existence threatened by an asteroid, one potential recourse would be to smash the looming space rock into pieces — but new research suggests that that approach may be less likely to succeed than people hope.

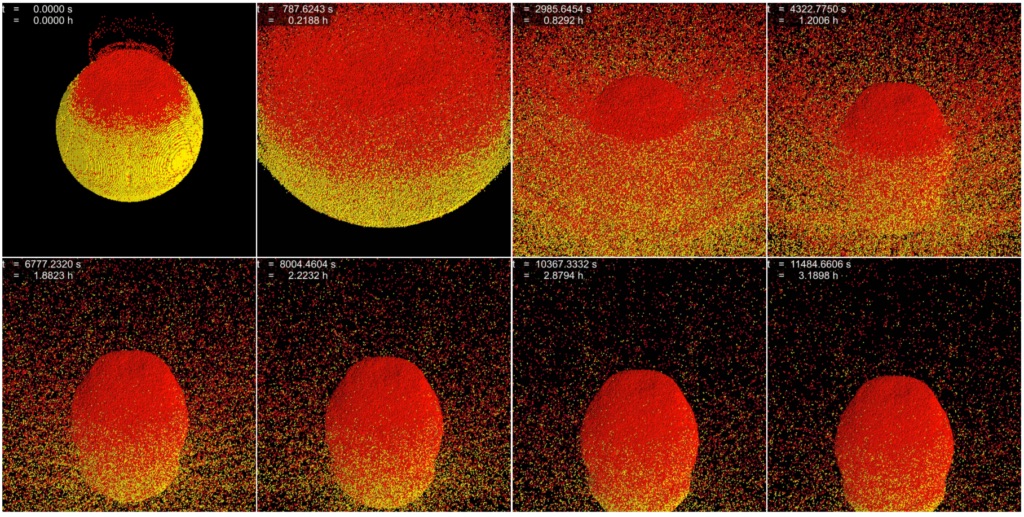

The research suggests that an asteroid wouldn't break apart as drastically as previous models suggested, and that in the aftermath of the attempted destruction, the asteroid's gravity would be strong enough to pull the fragments back together.

"It may sound like science fiction but a great deal of research considers asteroid collisions," lead author Charles El Mir, a recent doctoral graduate at Johns Hopkins University, said in a university statement. "For example, if there's an asteroid coming at Earth, are we better off breaking it into small pieces, or nudging it to go a different direction? And if the latter, how much force should we hit it with to move it away without causing it to break? These are actual questions under consideration."

Answering those questions, unsurprisingly, would be easier if we knew more about asteroids — the authors wrote that even when it comes to asteroids that scientists have density estimates for, they typically aren't sure what their interior structure is. Nevertheless, simulations let them model asteroids with a broad range

The results bode well for asteroids, at least. "We used to believe that the larger the object, the more easily it would break, because bigger objects are more likely to have flaws," El Mir said. "Our findings, however, show that asteroids are stronger than we used to think and require more energy to be completely shattered."

Of course, asteroids aren't just potential threats — they also intrigue scientists because they are leftover rubble from the formation of the solar system, and some hope that they could become resources for companies seeking to mine their water and metals.

The research is described in a paper published in the March issue of the journal Icarus.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- 7 Great Movies Featuring Earth-Threatening Asteroids

- Asteroid Science: How 'Armageddon' Got It Wrong

- Humanity Will Slam a Spacecraft into an Asteroid in a Few Years to Help Save Us All

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.