The end may be near for ice-hunting Artemis 1 moon cubesat

There apparently isn't much time left to save NASA's LunaH-Map cubesat.

The tiny probe was one of 10 cubesats that launched as ride-along payloads last November on Artemis 1, the first-ever mission of NASA's moon-bound Artemis pogram.

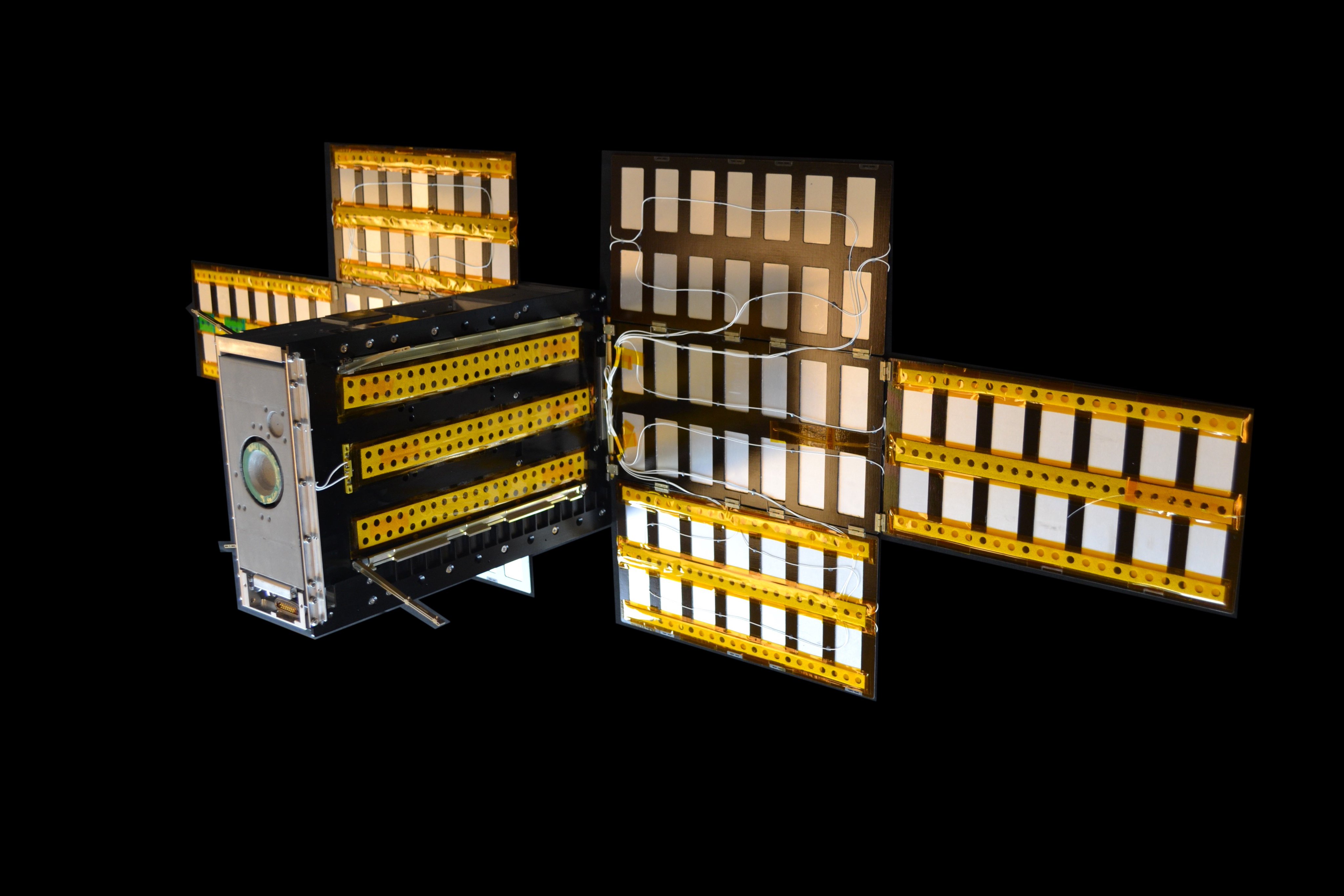

LunaH-Map aimed to map the abundance and distribution of water ice near the south pole of the moon. But the spacecraft failed to perform a crucial engine burn five days after liftoff and didn't get into lunar orbit as planned.

Mission team members soon traced the problem to a stuck valve in the cubesat's propulsion system. They've been trying to troubleshoot it ever since, but those efforts may wrap up soon.

"If we cannot ignite the [propulsion] system, we are likely to end operations at the end of May," LunaH-Map principal investigator Craig Hardgrove, of Arizona State University, said on Monday (May 1) at the Interplanetary Small Satellite Conference, according to SpaceNews.

Related: The 10 greatest images from NASA's Artemis 1 moon mission

The Artemis 1 cubesats were integrated into a stage adapter on NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) megarocket in the fall of 2021, as SpaceNews noted. But the mission didn't get off the ground until the following November, thanks to technical issues and bad weather.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That delay may be the ultimate cause of the problem that afflicted LunaH-Map, Hardgrove said.

"We had informed NASA that this propulsion system was not built to withstand a long launch delay, longer than four or five months," he said on Monday, according to SpaceNews.

LunaH-Map wasn't the only Artemis 1 cubesat to have a rocky road after liftoff. For example, Japan's OMOTENASHI spacecraft suffered a communications problem that prevented it from dropping a tiny lander on the moon. And NEA Scout, which aimed to solar-sail its way to a near-Earth asteroid and then study the space rock up close, never phoned home after the Nov. 16 launch.

But the mission teams of all the Artemis 1 cubesats should hold their heads up high, Hardgrove said.

"Characterizing any of them as a failure is not fair," he said, according to SpaceNews. "They've all developed a substantial amount of technology."

Artemis 1 succeeded overall, sending an uncrewed Orion capsule to lunar orbit and back. NASA is now gearing up for Artemis 2, which will launch four astronauts around the moon in late 2024, if all goes according to plan. Artemis 3, which will put boots down near the lunar south pole, is scheduled to follow a year or so later.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.