A Tale of Two Apollo 'Goodwill' Moon Rocks: One a Marvel, the Other Missing

Precious lunar samples have curious histories.

OTTAWA, CANADA — During the Apollo program, NASA gave moon rocks to its allies — and various countries have since misplaced them.

A number of moon rocks gifted in the wake of the Apollo 11 and Apollo 17 missions (which took place in 1969 and 1972, respectively) are … well, somewhere. The Canadian Museum of Nature recently put its Apollo 17 rock out for display, but the location of the country's Apollo 11 rock (which is not under the museum's jurisdiction) remains unknown.

The museum argues that the Apollo 11 rock probably isn't missing per se, but is likely misplaced — perhaps sitting in a filing cabinet somewhere after it was handed over to Canadian politicians in 1970.

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing

This is not a situation unique to Canada. Space.com partner site collectSPACE, in consultation with former NASA Office of Inspector General Special Agent Joseph Gutheinz, who is now a professor at the University of Phoenix, has been trying to track down many of these moon rocks around the globe since 2002. These efforts and progress to date for gifts from Apollo 11 and Apollo 17 are listed on individual collectSPACE pages.

"Once gifted, each of the goodwill moon-rock samples became the property of the recipient entity and therefore was no longer subject to being tracked by NASA," collectSPACE explained. "All other lunar samples' locations are well documented by the U.S. space agency to this day."

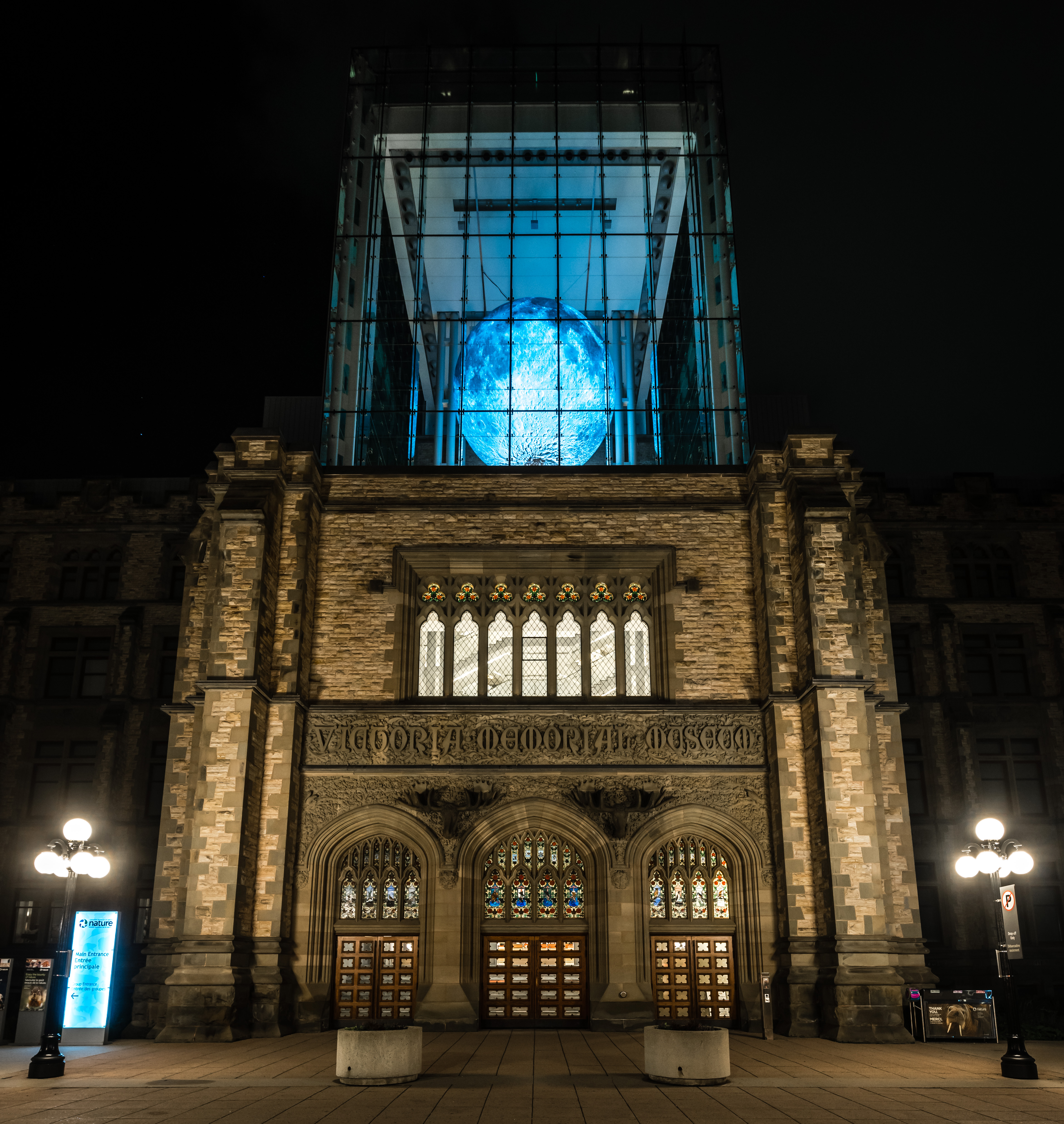

While the whereabouts of the Apollo 11 rock in Canada remains unknown, the Apollo 17 rock was displayed for the public just in time for the national holiday, Canada Day, on July 1, and shortly before the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing on July 20. The memento has been on brief display in the past. This time around, it will be visible to the public in the nature museum downtown until at least Oct. 25.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

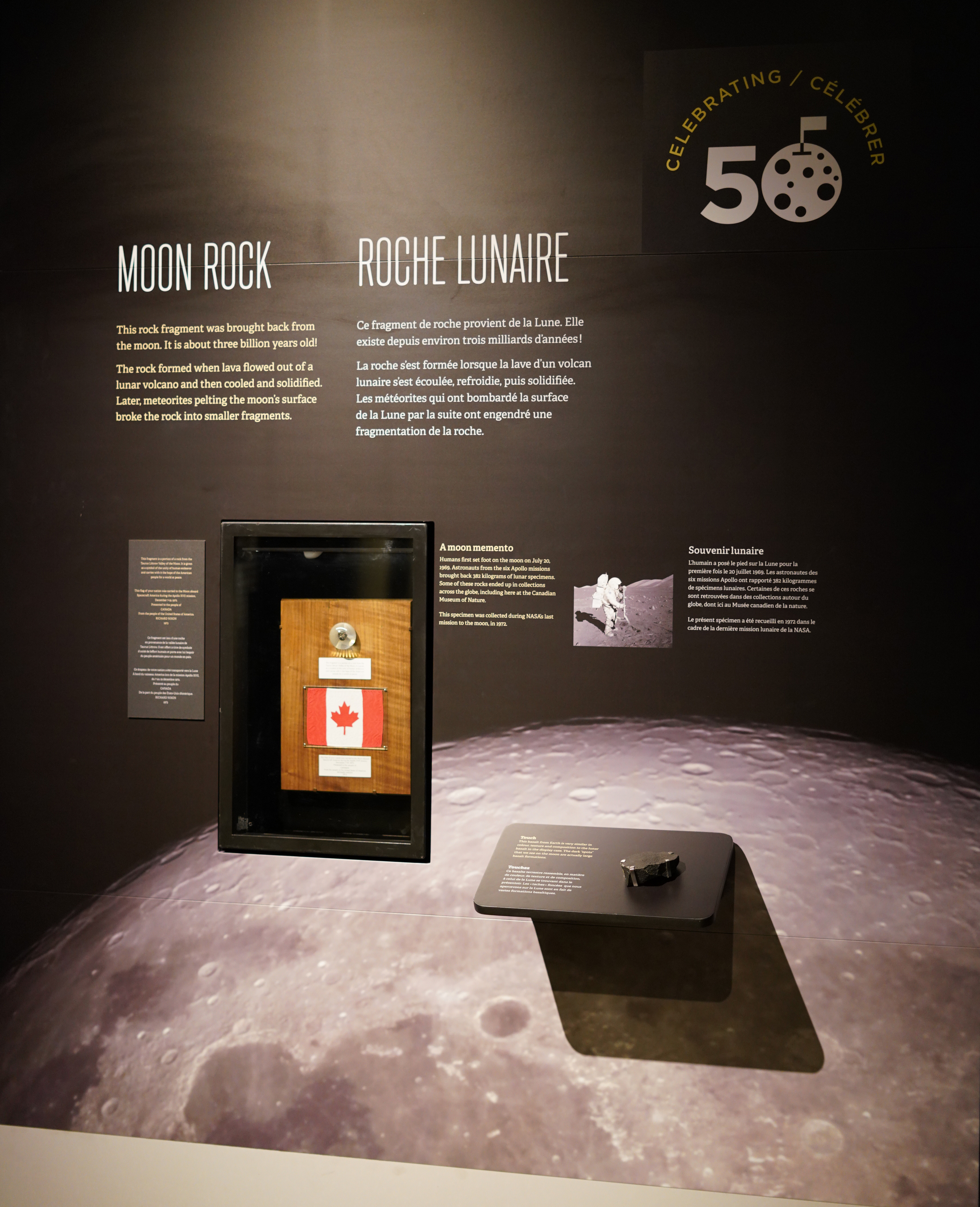

"It's a Lucite ball with the moon rock in it, and there's a wooden plaque with a Canadian flag that actually went up to the moon," Erika Anderson told Space.com; she's the museum's curator of mineralogy (a collection which also, incidentally, includes 3,000 meteorites along with this lunar rock). Like all the goodwill rocks presented to other nations, the Canadian Apollo 17 rock is a fragment of sample 70017 brought back during the last human moon mission, and includes a friendly inscription from then-U.S. President Richard Nixon.

Incidentally, the Apollo 17 fragment comes with a backstory, Anderson said. Fourteen-year-old Jaymie Matthews - who is today an exoplanet researcher at the University of British Columbia - attended the launch in December 1972. He went as a youth ambassador after he, by his own account, lied about his age and won a national essay contest open to older teens and young adults.

Months later, Matthews received the precious sample on behalf of Canadians;he handed it over to Canada's head of state, the governor general, who eventually gave it to the museum. Matthews commented in a blog post from 2018 that the rock went missing during the mid-1970s while traveling in an exhibit. Decades later, Matthews added, he Googled several keywords and found a photo of the moon rock in storage at the museum. However, museum spokesperson Laura Sutin told Space.com that the museum has "no record of the [Apollo 17] moon rock ever being in a traveling exhibit, nor going missing."

This isn't the organization's only effort at space exploration awareness this summer. A huge glass-gallery room on an upper floor of the museum — clearly visible from the outside streetscape — is now displaying a large, illuminated moon globe, literally highlighting for visitors the Apollo celebrations – even after dark.

Inside, an exhibit called "Otherworlds: Visions of our Solar System" (on display until Sept. 2) has artist Michael Benson blending art and real data from spacecraft across the universe to create unique landscapes.

- NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

- Reading Apollo 11: The Best New Books About the US Moon Landings

- NASA's Apollo Program History: Our Complete Coverage

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.