50 years ago, an Apollo 14 astronaut played golf on the moon. Here's the inside story.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Most golfers really want to avoid sand traps, but NASA astronaut Alan Shepard had no choice but to deal with one when wielding a six-iron head on the moon's dusty surface 50 years ago this month.

Shepard took a few moments during the Apollo 14 landing to show off his hobby during a live broadcast from the lunar surface on Feb. 6, 1971. He took two shots, with the second ball going "miles and mile," he said on-camera.

He was exaggerating, according to new analysis from the United States Golf Association (USGA). Based on data from the crew and a modern-day moon mission, the group found that the first ball traveled 24 yards (22 meters) and the second about 40 yards (37 m). By comparison, a 2019 report using golf tournaments' gender categories shows that an average amateur male golfer on Earth can drive the ball 216 yards (198 m), and an average female golfer 148 yards (135 m), although those distances have increased significantly since Shepard's flight.

Related: Apollo 14: NASA's 'rookie' astronauts bring golf to the moon (photos)

To be fair to Shepard, however, he had more obstacles to contend with than your typical Sunday hobbyist. His golf "club" was actually a modified sample collection device with the head attached to the end. He was also wearing a notoriously stiff spacesuit that forced him to swing with a single arm.

"You can only get a one-handed shot, which really doesn't give you the strength and speed of a normal golf shot on Earth," USGA historian Victoria Nenno told Space.com. "You normally have a lot of turn [at the waist], and strength coming from legs. Unfortunately, Shepard was only able to manage a one-handed shot."

In contrast, Nenno said, Earth-bound golfers have enjoyed technical advances like moisture-wicking technology in clothing, that Shepard would not have had access to in the 1970s, even on his home planet. For that reason, she added she was intrigued to hear of newer, more flexible moon spacesuits NASA is creating for the Artemis program for possible landings in 2024. "It would be very interesting to see how that would affect the shot," Nenno said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

USGA found the lunar golf balls in high-resolution, enhanced scans of the original flight footage of the Apollo 14 mission. The association measured the point between divot and locations where the balls ended up using high-resolution images from orbit taken by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which launched in 2009.

The association used a second technique to confirm the measurements. Some of the images used were photo sequences taken from the lunar module, the astronauts' landing craft, taken to show the entire landing site to geologists on Earth. USGA stitched the photographs into a panorama to demonstrate the location of the divot and the two balls, which (after taking the new photo enhancements into account) were well within view of the landed spacecraft.

The two balls are also visible in Apollo 14 takeoff footage, but only after applying "a complex stacking technique on multiple separate frames," according to a USGA Golf Journal story. This means NASA astronauts Shepard and Ed Mitchell likely couldn't have seen the balls themselves from the spacecraft, either during their time on the ground or when flying away from the moon.

Happily for golf fans, Shepard found room to tuck away his modified club in the lunar module; that was lucky given that astronauts often discarded equipment on the moon to make room for precious rock samples. The rules surrounding giving space artifacts to astronauts were different in the 1970s, so Shepard kept the club before donating it to the USGA Museum in Liberty Corner, New Jersey, roughly an hour west of New York City, in 1974.

Shepard was convinced to part with his precious moon club after the famed singer and entertainer Bing Crosby, a member of the USGA committee in 1972, wrote Shepard saying the museum would be "an ideal repository for the celebrated implement," Nenno said. Shepard and Crosby were already acquainted from playing together at Pebble Beach, California, a well-known golf haven for enthusiasts.

Nenno said the artifact is typically one of the most popular in the museum — not taking into account the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and associated quarantine rules, of course, which have affected tourist destinations worldwide. "The Apollo program represented national pride and hope for the future. The artifact has a lot of those great feelings attached to it; the look of it is unusual and interesting compared to other golf equipment," she explained.

Why "unusual and interesting"? Technically speaking, the golf club was a Wilson Staff Dyna-Power 6-iron head attached to a sampling tool — a five-piece tool loosely held together by string when not fully assembled — that was made of aluminum and Teflon. Golf clubs usually don't come apart as Shepard's moon club did, but Shepard needed the modification to fold it into the cramped quarters of the Apollo lunar lander.

Shepard got the idea for his golf moonshot in 1970, when famed golfer Bob Hope visited NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC, now Johnson Space Center) in Houston, the training hub for astronauts, for a television special. Hope took his golf club everywhere, according to the USGA, and Shepard was inspired to do a quick golf session on the moon to demonstrate the moon's gravitational pull, which is one-sixth that of Earth, according to NASA.

Shepard, the commander of Apollo 14 and a long-time NASA astronaut, used his connections to discreetly ask for help keeping the plan a surprise. Jack Harden, the pro at River Oaks Country Club in Houston, made the clubhead. NASA's technical services division also assisted with the golf "club" construction, which had to meet the same strict safety requirements as other spacecraft payloads.

Shepard also made sure to clear his golf shot with senior management, approaching then-MSC director Bob Gilruth to get buy-in. At first, Shepard recalled in a 1998 NASA oral history, Gilruth said "there was absolutely no way." Shepard, however, explained the golf club's construction to Gilruth and then made the director a promise.

"The thing that finally convinced Bob was when I said, 'Boss, I’ll make a deal with you. If we have screwed up, if we have had equipment failure, anything has gone wrong on the surface where you are embarrassed or we are embarrassed, I will not do it. I will not be so frivolous,'" said Shepard at the time.

"I want to wait until the very end of the mission, stand in front of the television camera, whack these golf balls with this makeshift club, fold it up, stick it in my pocket, climb up the ladder, and close the door, and we’ve gone," Shepard said. "So he finally said, 'Okay.' And that’s the way it happened."

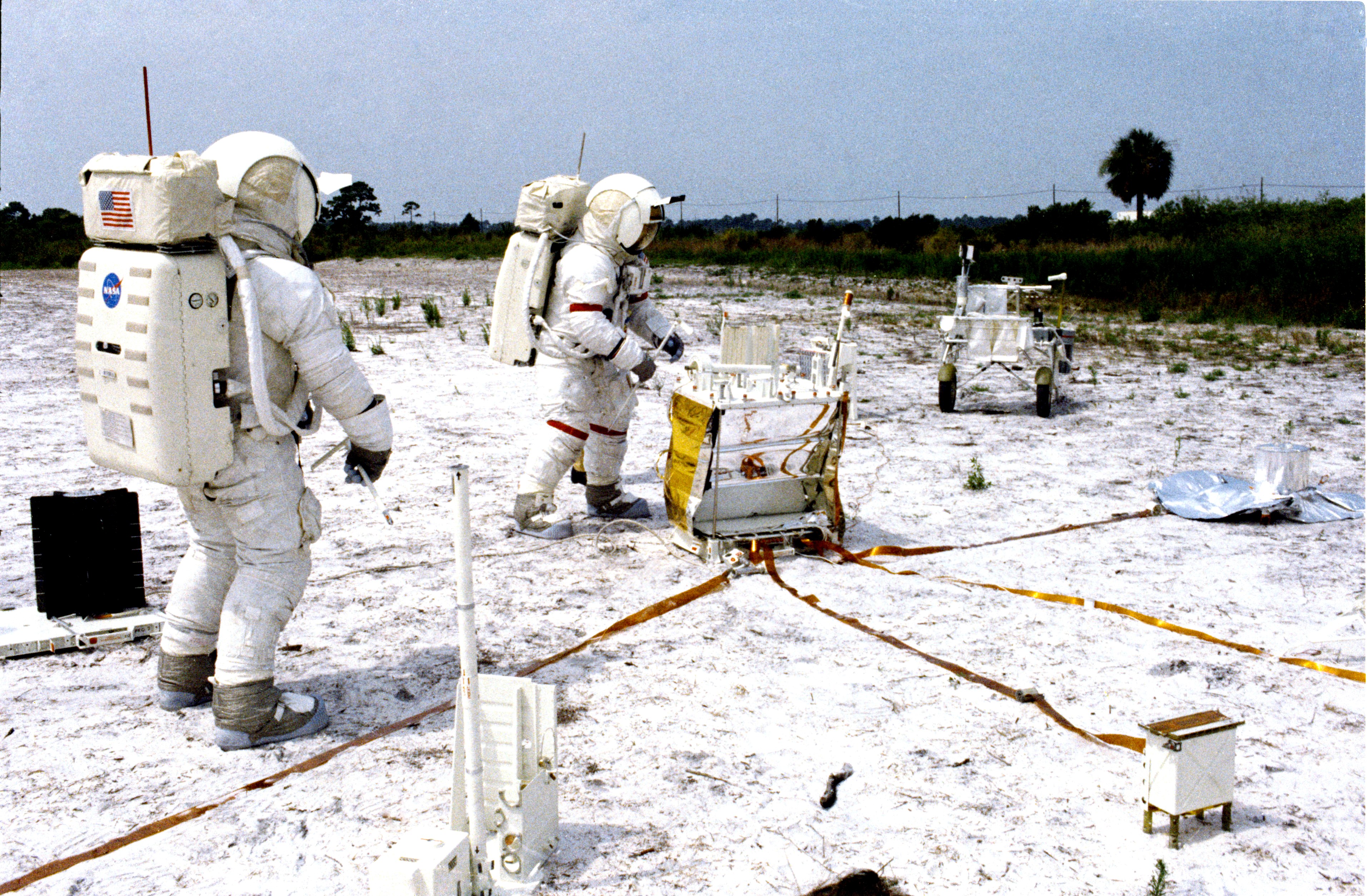

Like any good astronaut, Shepard simulated his golf shot long before making it to the moon. He would regularly haul his more than 200-lb. (90 kilograms) spacesuit to a local bunker to practice his shot while suited up, away from the public eye, just to make sure he could land it, USGA said.

Decades after the historic golf excursion, Shepard still had pride in the accomplishment. "So far I'm the only person to have hit a golf ball on the moon. Probably will be for some time," he told NASA in the February 1998 oral history, a few months before his death at age 74. He marveled at how different an experience was golfing on the lunar surface. "What a neat place to whack a golf ball."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.