Citizen Scientists Are Helping Find Alien Planets in NASA's TESS Data

Citizen science finds some exoplanets that computers couldn't.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — When it comes to finding exoplanets, more computing power isn't always the answer.

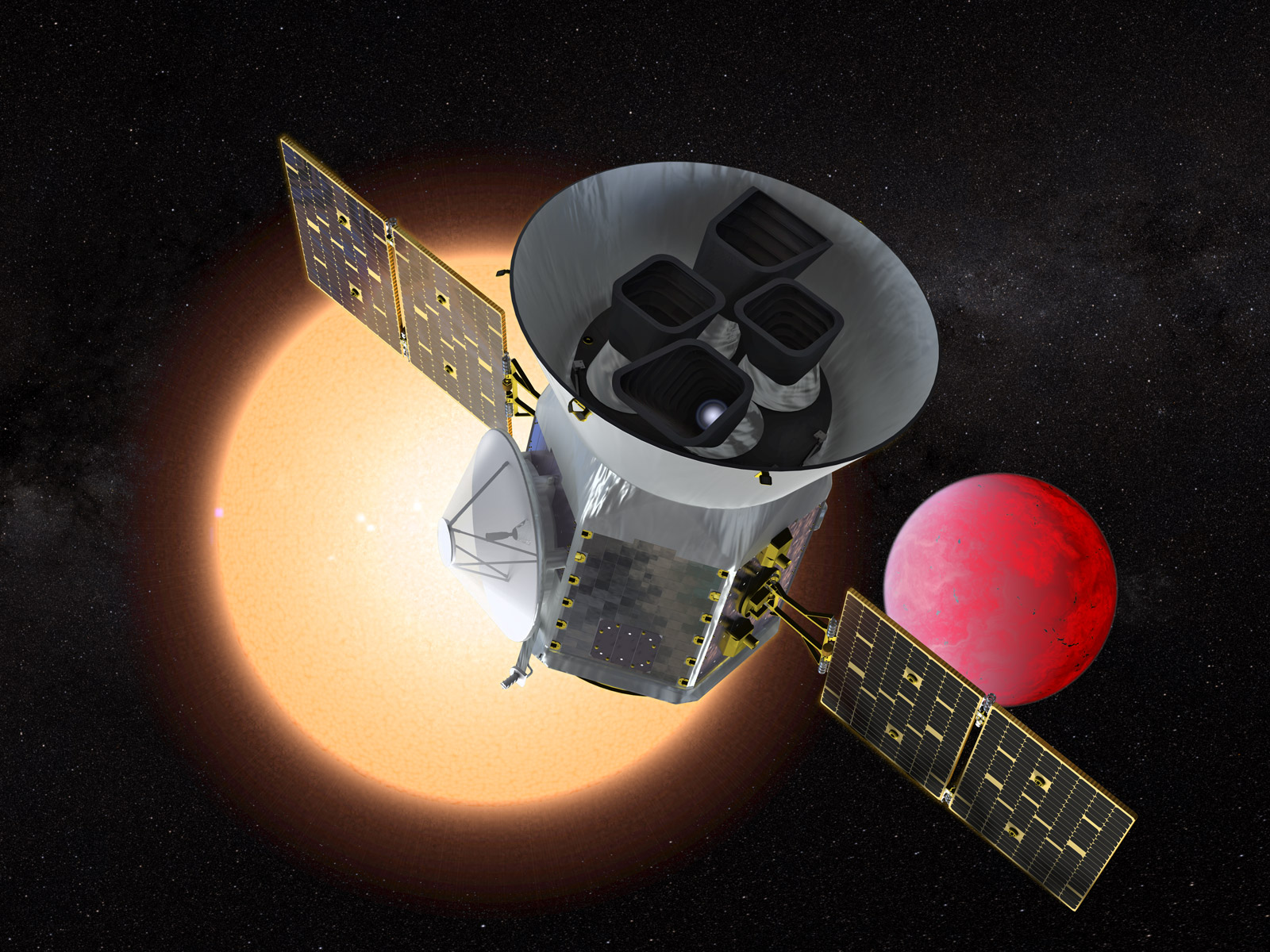

In a talk given here at the TESS Science Conference at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on July 30, Nora Eisner introduced the audience to the positive impact citizen science has already had on the search for exoplanets. This effort has used data gathered by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), via a project Eisner helms called Planet Hunters TESS.

It might seem more efficient to rely on computers to sort through the reams of data coming from TESS as it makes its way into its second year of operations. But Eisner told Space.com that human computers have an advantage in finding easy-to-miss planets.

Related: NASA's TESS Exoplanet-Hunting Mission in Pictures

"There are certain types of transits that machines and algorithms just miss," Eisner, an astrophysics doctoral student and exoplanet researcher, told Space.com. ("Transits" are the passages of planets across their stars' faces, which cause small brightness dips that TESS hunts.)

"Most algorithms have a two- or even three-transit detection threshold," she added. "That basically limits what we're finding to shorter-period planets. [But] there's lots of single-transit events, and machines aren't particularly good at finding those, whereas human eyes are really good [at it]. Humans are equally likely to be able to identify a single-transit event as they are to be able to identify a multitransit event."

Eisner said that planet hunters need no prior knowledge of space science. Program participants can be as young as grade schoolers and are found across the world. After joining, participants go through a short training program that introduces them to the key scientific concepts — namely, how to look for the dips in a light curve that suggest that a transiting exoplanet may have crossed a star's face.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

After that, it’s off to the races, and boy do they race, said Eisner.

"We get through data very, very quickly," she said. "I think we had a million classifications within the first week."

To make a classification, Eisner said, eight to 15 volunteers must check a light curve for the presence of a transit. For light curves identified by volunteers as possible transit events, the Planet Hunters TESS team makes a ranked list, going from most likely to least likely. The team uses machine learning to create a significance for each transit-like event. From that list, Eisner said, the Planet Hunters TESS science team looks at the top 500 for further verification.

In TESS's first year of operations, the over 12,000 registered volunteers (and even more unregistered ones) made 9 million classifications, Eisner said.

While these kinds of results are exciting, citizen-science approaches to data collection have certainly garnered skepticism in the past, from both scientists and nonscientists. But what helped Planet Hunters TESS succeed, Eisner told Space.com, is the legacy of science and nonscience community participation laid out by TESS's predecessor, NASA's prolific planet-hunting Kepler space telescope.

"Everyone's been so supportive," said Eisner. "I think that it also helps that this has already previously been done. The initial Planet Hunters, which ran with the Kepler data, was really successful. They actually identified lots and lots of candidate [exoplanets]. And I think, especially with this, because stars are so varied, it's so good to have people looking at [the data]."

You can learn more about Planet Hunters TESS at the organization's website.

- The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)

- TESS: NASA's Search for Earth-Like Planets

- Alien Planet Quiz: Are You an Exoplanet Expert?

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Sarah is a D.C.-based independent science journalist interested in the philosophical questions of science and technology and how research intersects with our daily lives. Her work has appeared in Popular Mechanics, IEEE Spectrum, Inverse, and Nature, among other outlets, and covers topics ranging from AI to particle physics and space travel. She has a master's degree in science journalism from Boston University.