Similar, But Different: Huygens Probe Unlocks Another Planet in Our Solar System

With the successful landing of the European Space Agency's Huygens probe on Saturn's moon Titan, we can now bring the number of bodies in the solar system that have been landed on by a spacecraft up to four (or five, if you count the soft-crash-landing of the NEAR spacecraft on the asteroid Eros). The Moon has been the most visited, with robotic landers from the former Soviet Union and from NASA, as well as six successful landings with astronauts in the late 1960's and 1970's. The planet Venus was visited by four successful unmanned landers from the former Soviet Union in the 1970's, and the planet Mars has been visited successfully by a variety of NASA robotic landers starting in the 1970's with the two Viking landers, 1997's Mars Pathfinder, and 2004's Spirit and Opportunity rovers.

So what have we learned from this planetary exploration? While orbiting spacecraft can map the surfaces of planets, and provide big-picture geological context, there's no substitute for actually landing on the surface of another world to get an idea of what it's really like there. Especially for us humans, it's much easier to picture ourselves on the ground of an alien world with pictures taken from the surface than with pictures taken from orbit. You can imagine that you're really there, and sometimes there's just no substitute, scientifically, for a little pretended sightseeing.

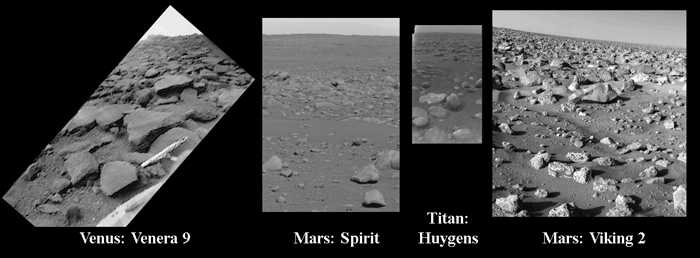

The accompanying image contains landscapes from spacecraft that have landed on three worlds with atmospheres - Venus, Mars, and now Titan. Airless bodies like the Moon have a very different surface environment, which is mainly shaped by eons of impact cratering. On airless worlds, this cratering results in a thick, broken-up surface layer called a regolith that appears as a softened, dusty layer a few meters thick or more.

Planets or satellites with atmospheres, on the other hand, have a whole range of available geological processes that can shape their surfaces. While the surface of the Earth is primarily shaped by liquid water, even in the most arid regions, as well as by the presence of life, drier worlds like Venus and Mars have different landscapes. Even a cold, dry place like Mars, however, shows signs of geological activity produced by liquid water in many places - water is such an effective agent of geological change that even relatively ancient, or rare, occurrences may be preserved and appear dominant. The other major geological factor is wind - even on Mars, with its relatively thin atmosphere, wind has sculpted the surface, smoothing rocks and distributing dust on a global scale.

The surface of Mars is, of course, heterogeneous - different regions of the surface vary distinctly in appearance and predominant geological activity. Think of the views from the recent Spirit and Opportunity landers, for instance. Still, some regions of Mars look strikingly similar, as in the Spirit and Viking 2 lander images shown here. The surface is strewn with rocks, some of which have been smoothed by the action of water or wind over geological time. The rocks are interspersed with patches of smoother sandy soil.

Worlds like Venus are much harder to understand. Venus is a planet predominantly shaped by volcanic activity. While we have only a few views of the surface of Venus under its thick clouds (a similar situation to Titan), the view from Venera 9 is strikingly similar to the views of Mars. Rocks are seen, although they are more angular and less weathered than the rocks visible on Mars, perhaps due to the dense atmosphere which limits surface wind speeds on Venus to a few km/hour. Acid rain may also produce some chemical and mechanical weathering of rocks at the surface. Other regions of the surface of Venus have a smoother, more plate-like appearance, perhaps due to a different sort of volcanic activity.

Perhaps most surprising in our views of worlds with atmospheres is the new view of Titan's surface. Titan, with its thick atmosphere, extremely cold surface temperature, and suspected surface composition of various exotic hydrocarbons, would seem worlds away from the comparatively more Earth-like inner solar system. Yet the surface image from Titan, shown here, reveals a surprisingly familiar-looking surface - blocks of material, thought to be water and/or hydrocarbon ice, are interspersed with regions of darker, smoother-looking material that appears similar to the dust or soil seen between rocks on Mars or Venus. The ice blocks of Titan even appear to have some erosion at their bases that could be due to fluvial processes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It seems unlikely that three worlds that are so different - hot, volcanic Venus, with a surface temperature of over 700 K; cold, dry Mars with a surface temperature of about 200K; and even colder, exotic Titan with a surface temperature of about 94K - could have surfaces that appear so similar. Yet the similarities are striking - the view of Titan's surface could easily be mistaken for the more familiar Mars, or even for Venus! In fact, some dry, arid regions of the Earth itself have a similar appearance.

While our new view of Titan's surface might seem almost disappointingly familiar for such an exotic place, it is perhaps an indication of the commonality of geological processes everywhere in the solar system. This fact should be reassuring - the action of wind and fluids produces similar results whether the temperature is near the melting point of rock or cold enough to freeze most volatile materials. Material is emplaced onto the surface, whether molten rock or molten ice, and then acted upon by liquids and gases over millions of years, causing it to slowly degrade. Apparently, these processes result in a similar appearance, independent of surface temperature or atmospheric thickness.

The analysis of the Huygens results is just beginning, and doubtless we will find many ways in which Titan is completely unlike anywhere else in the solar system. Perhaps it is reassuring, then, that we at least think we understand some of the fundamentals, even if the details are completely unknown and probably exotic. The solar system is a pretty amazing place!

Touchdown on Titan: Huygens Probe Hits its Mark

SPACE.com Special Report: Cassini-Huygens at Saturn and Titan