Sun's Wind Is Lowest Ever Recorded

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A wind of charged particles that stream constantly fromthe sun is at its lowest level ever recorded in the 50 years since spacecrafthave made the measurement possible.

The Ulyssesspacecraft observed the weak solar winds, the constant, high-speed streamof particles that races from the sun, during a quiet period in the sun'sactivity. The solar weather cycle affects Earth and other planets in the solarsystem.

"We know that the sun has been this cool before,this inactive before," said Nancy Crooker, a physicist at BostonUniversity in Boston, Mass., during a NASA teleconference on Tuesday. "Butthat was prior to the Space Age, so we didn't have actual physical measurementsuntil now."

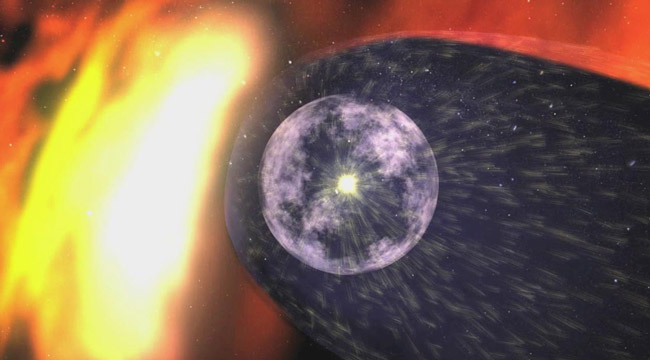

The solar wind's charged particles blow out from the sunat a blistering 1 million mph, sweeping away background radiation and collidingwith incoming galactic cosmic rays from distant stars. It effectively enclosesour solar system in a protective bubble called the heliosphere.

For Ulysses, the finding is a swan song. The probe, whichis dying, has spent the past 17 years watching the solar wind rise and fallduring the sun's 11-year cycle of activity. Fast and steady solar winds camefrom the upper latitudes, while more unpredictable, slower solar winds blewfrom the sun's equator.

But during the sun's latest quiet period, the spacecraftfound that the overall solar wind is 20 to 25 percent weaker, in terms ofpressure and density, than during the previous solar minimum. Weaker solarwinds mean a smaller and leakier heliosphere bubble, a protective sheath thatsurrounds the entire solar system. That means more background cosmic radiationgets through.

The danger to Earth from galacticcosmic rays remains rare in any case. However, future missions to the moonor Mars would probably try to plan the best times to travel outside ofEarth's own protective magnetosphere bubble. Astronauts on the InternationalSpace Station and the space shuttle remain safely within Earth's magnetosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When the sun is active,charged solar particles present risks to astronauts and even satellites.

"During a solar minimum there's relatively littlesolar radiation, so the primary risk is more from galactic cosmic rays,"said Dave McComas, a Ulysses scientist at the Southwest Research Institute inSan Antonion, Texas.

Current studies suggest that astronauts should undertakelong-duration missions during solar maximums, when increased solar activitystill poses a risk but also shields better against the constant threat ofgalactic cosmic rays, McComas added.

The solar wind's effects are also felt at the edge of thesolar system, where the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes have entered the heliosphere'souter envelope layer. Voyager 2 arrived at the solar system edge later thanVoyager 1, yet found that that boundary to be almost a billion miles closer ? apossible sign of the shrinking protective bubble.

The wanderings of Ulysses are drawing to a close with itslatest observations of the sun. The spacecraft can only look forward to an icy space tombonce its radioisotope thermoelectric generators fail to provide enough heat tokeep the onboard hydrazine fuel from freezing.

However, scientists expressed nothing but satisfactionwith the joint NASA-European Space Agency mission, which has lasted four timeslonger than the spacecraft's expected lifetime.

"For the first time we've got a spacecraft thatflies over the poles of the sun," said Ed Smith, a Ulysses scientist atthe Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "That allows us to seechanges in the heliosphere in three dimensions, or four if you counttime."

At least one lingering question still stands out —whether the current weak solar winds represent an isolated phase or a longerterm trend in future solar cycles.

- Video ? Ulysses RIP

- Video Player: Sun Storms

- The Best Images of the Sun

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.