A Wild 'Interstellar Probe' Mission Idea Is Gaining Momentum

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

New ideas for a robotic interstellar mission are percolating.

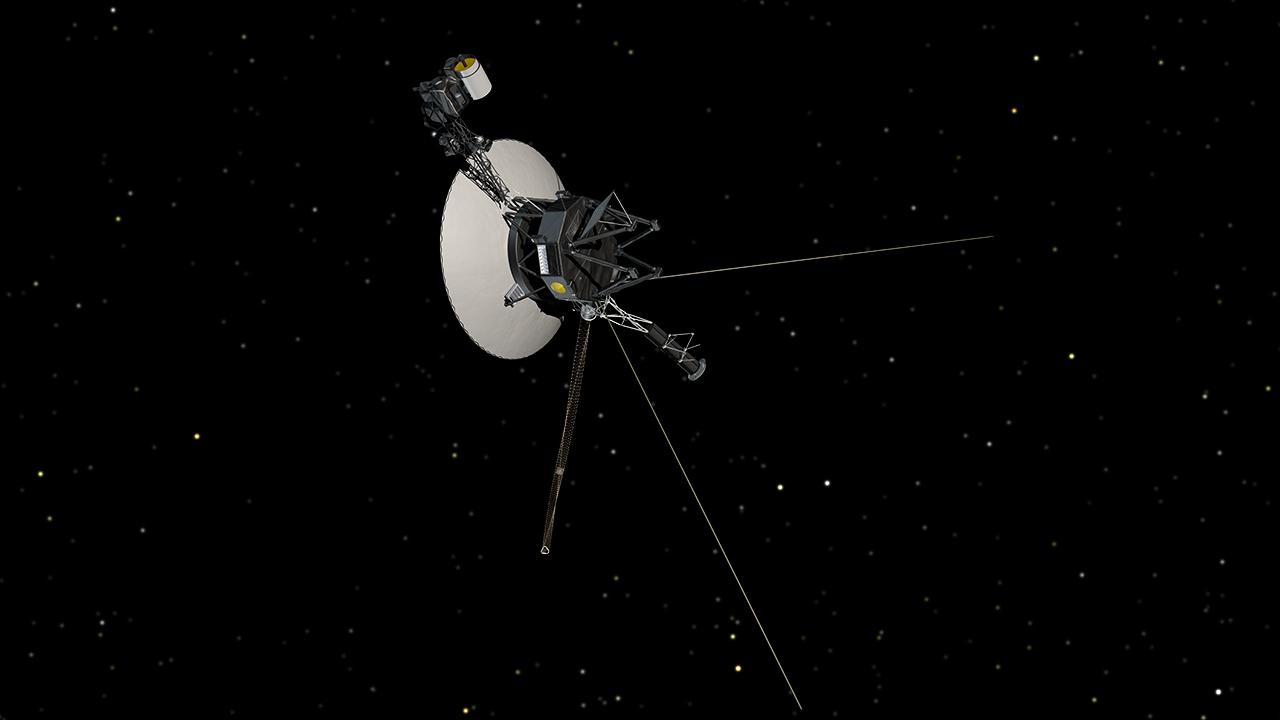

Ambitious science and strategic plans are being formulated for the fastest flight ever to interstellar space — almost six times faster than NASA's record-holding Voyager 1 spacecraft, which launched in 1977 and went interstellar in 2012.

With the goal of reaching 90 billion miles (145 billion kilometers) from the sun, the proposed robotic explorer would push the limits of engineering know-how and space technology, advocates say. [Gallery: Visions of Interstellar Starship Travel]

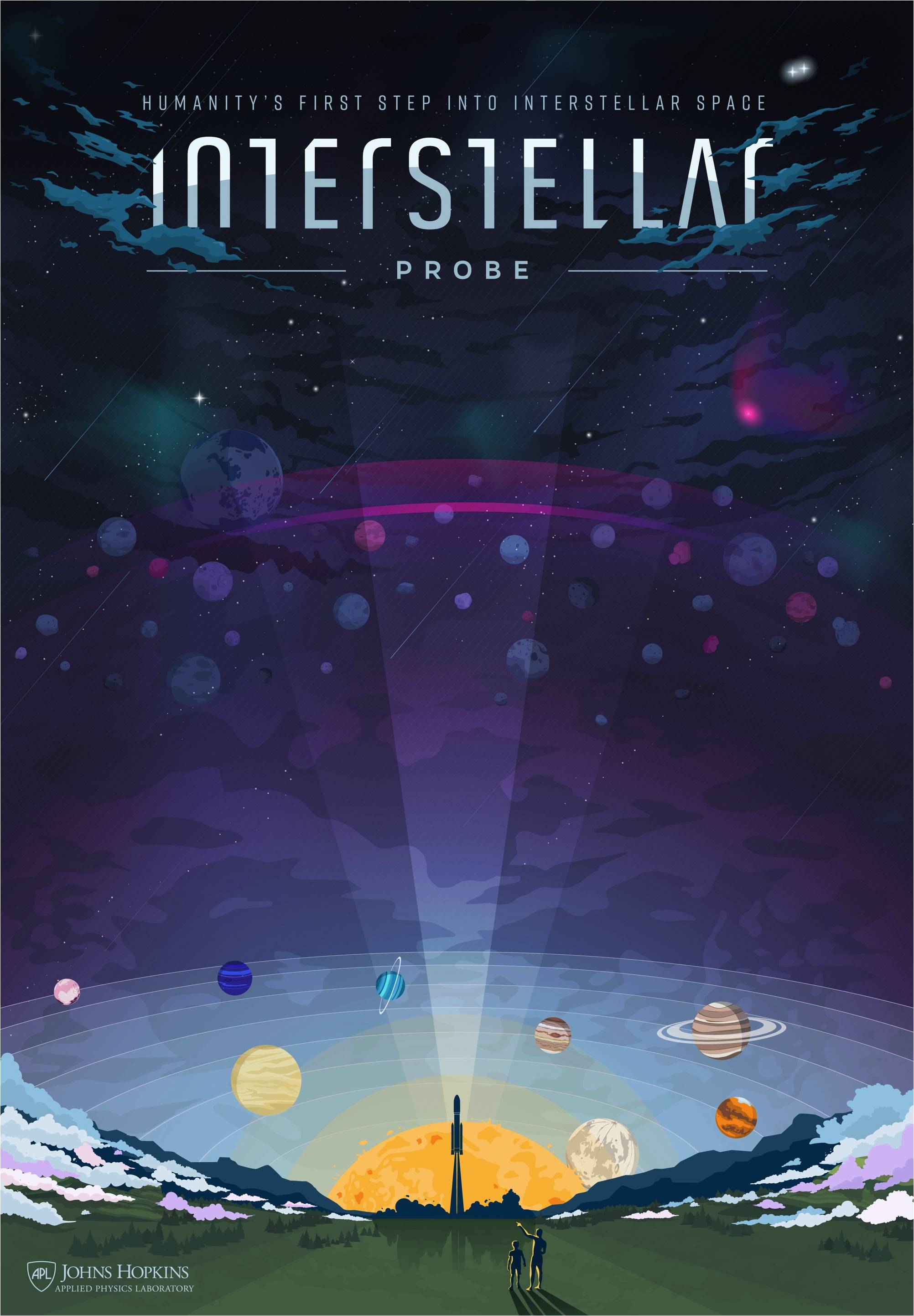

The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, is leading an international look at this prospect with a team of scientists and engineers studying a mission to the virtually unexplored space beyond our sun's sphere of influence.

"Overall, I think the study is progressing well and will provide some good and solid input for the next Decadal Survey round," said APL's Ralph McNutt, Interstellar Probe study leader and principal investigator. The Decadal Survey is based on studies led by the U.S. National Academies to provide a science community consensus on new undertakings in NASA space science and exploration.

First step

McNutt was lead author of an influential paper, "Near-Term Interstellar Probe: First Step," given at the 69th International Astronautical Congress held in October 2018 in Bremen, Germany.

The subjects of interstellar travel, interstellar probes and interstellar "precursor" missions are not new, the paper explained, "but have lacked traction with policymakers and the scientific community at large because of the states of both scientific knowledge and engineering realities."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Moreover, the paper's authors explained that the next step in reaching to the stars will require the recognition of engineering limits, scientific trades and scientific compromises, "but this is new neither in science nor exploration. Such a step would be an 'Interstellar Probe.' The time for that step has come."

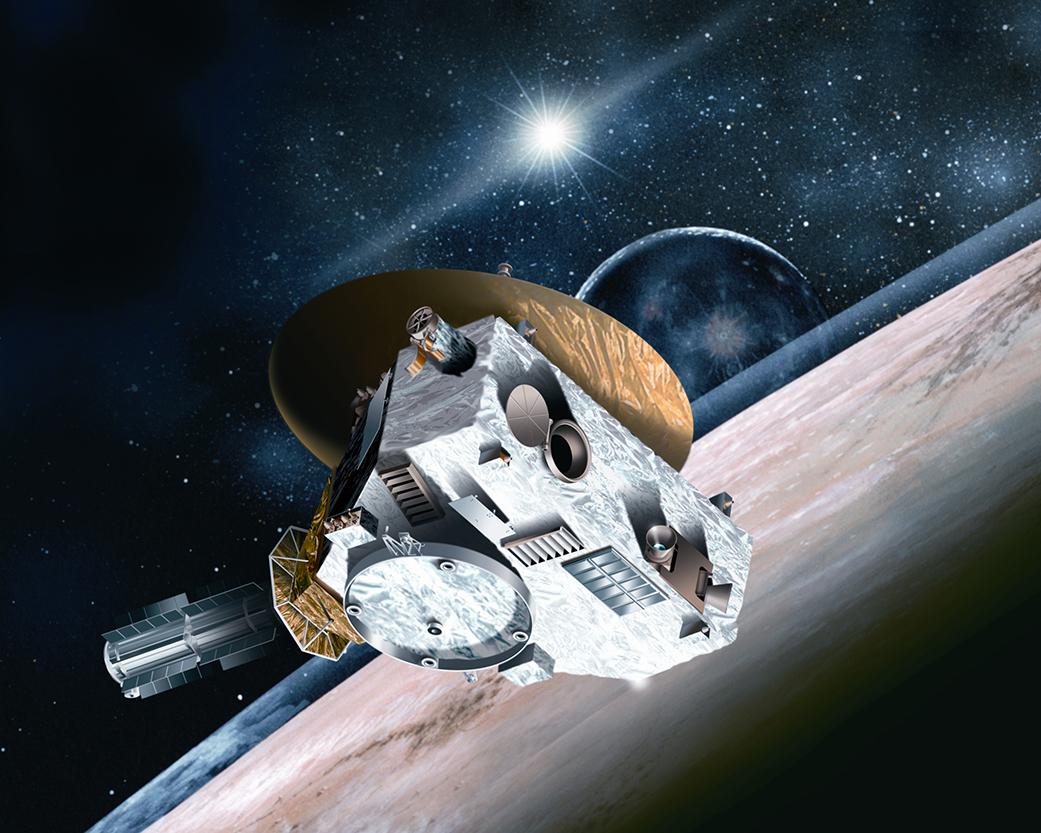

The successful launch of NASA's groundbreaking Parker Solar Probe in August 2018 provides one more step forward for a realistic look at all of the possibilities, McNutt and his colleagues said. In addition, new discoveries in the Kuiper Belt by NASA's New Horizons mission — which flew by Pluto in 2015 and the even more-distant small object Ultima Thule last week — underscore the possibilities of compelling science as motivation for an Interstellar Probe, the researchers said.

Learn by doing

Current thinking about going interstellar begins with an "interstellar precursor" mission — a spacecraft capable of traveling to perhaps 1,000 astronomical units (AU) using current and near-term technology. (One AU is the Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles, or 150 million km).

This approach is a good one, both because of its potential science return and its impact on driving propulsion, communications and sensor technologies forward, said Paul Gilster, writer and editor at the website Centauri Dreams, which discusses ideas for the exploration of deep space, including the interstellar realm.

"We learn by doing, and pushing well beyond the heliopause will teach us what to expect in the local interstellar medium, where future, faster missions will eventually explore inner Oort Cloud objects like Sedna and push on into the Oort itself," Gilster said. (The Oort Cloud, which is home to trillions of comets, lies between about 1,000 and 100,000 AU from the sun.)

The huge reaches of space beyond the heliopause — the bubble blown by the solar wind — are terra incognita, he told Space.com.

"We can't even think of missions to more distant targets without mapping the immediate terrain to learn about hazards that could affect equipment, disrupt communications or even destroy the spacecraft," Gilster said.

An interstellar precursor is a logical successor to New Horizons and the Voyagers that have preceded it, he added.

"It would be our first spacecraft truly designed for exploratory operations in interstellar space and would represent our intention to reach targets that today seem impossible, including one day the nearest stars," Gilster said. [Ultima Thule in Pictures: Flyby Views of 2014 MU69 by New Horizons]

Reasonable candidate

The APL study — which focuses on a mission that could launch before 2030 and reach 1,000 AU in 50 years — is based on the next extension of what we know we can do, propulsion physicist Marc Millis, founder of the Tau Zero Foundation, said.

"It is a reasonable candidate for the next deep-space mission," Millis told Space.com. "It is not, however, a true interstellar mission. It is better referred to as an 'interstellar precursor' mission."

Voyager 1 has traveled about 142 AU during its four decades in space. While the interstellar-precursor probe would explore much more distant realms, it wouldn't get anywhere near another star system, Millis stressed. One thousand AU is about 0.016 light-years, and the closest star to the sun, Proxima Centauri, lies about 4.2 light-years away.

Still, "in addition to the value of its destination-based science, it could be used to assess the challenges of an exoplanet probe," Millis said of the putative mission.

The APL work is one of many interstellar approaches, he added.

"Others aim for more ambitious missions that need varying degrees of technological advancements, from the seemingly simple space sails to the seemingly impossible faster-than-light space warps," Millis said.

Philosophical thoughts

Planning out futuristic interstellar missions also conjures up some deep, philosophical thoughts.

"We need to reach for extreme targets, because exploration has always defined our species," Gilster said. "Our voyages have crafted our aspirations."

A full-on interstellar mission has long been thought impossible, or at least impractical, he added, but we know now that technologies are becoming available that can make it happen.

"A successful mission to another stellar system could show us possibly habitable planets up close and help us put our own human experience in the context of billions of worlds that could support life," Gilster said. "Philosophically, we can't help ourselves. We have to know what's out there, and whether we are alone in the cosmos."

Gilster's bottom line: "A first interstellar mission will drive new breakthroughs in propulsion, with inevitable ramifications for travel in our own solar system as well. Culturally and scientifically, such a mission is inevitable. The only question is when."

Leonard David is author of the forthcoming book, "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" to be published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for SPACE.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.