NASA's New Horizons Ready for Historic Flyby of Ultima Thule in the Kuiper Belt

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft will ring in the new year with an epic flyby at the edge of the solar system, and the stage is set for a truly historic encounter. And it's happening amid a partial government shutdown that initially threw a curveball into how the New Horizons team will share the flyby with the public.

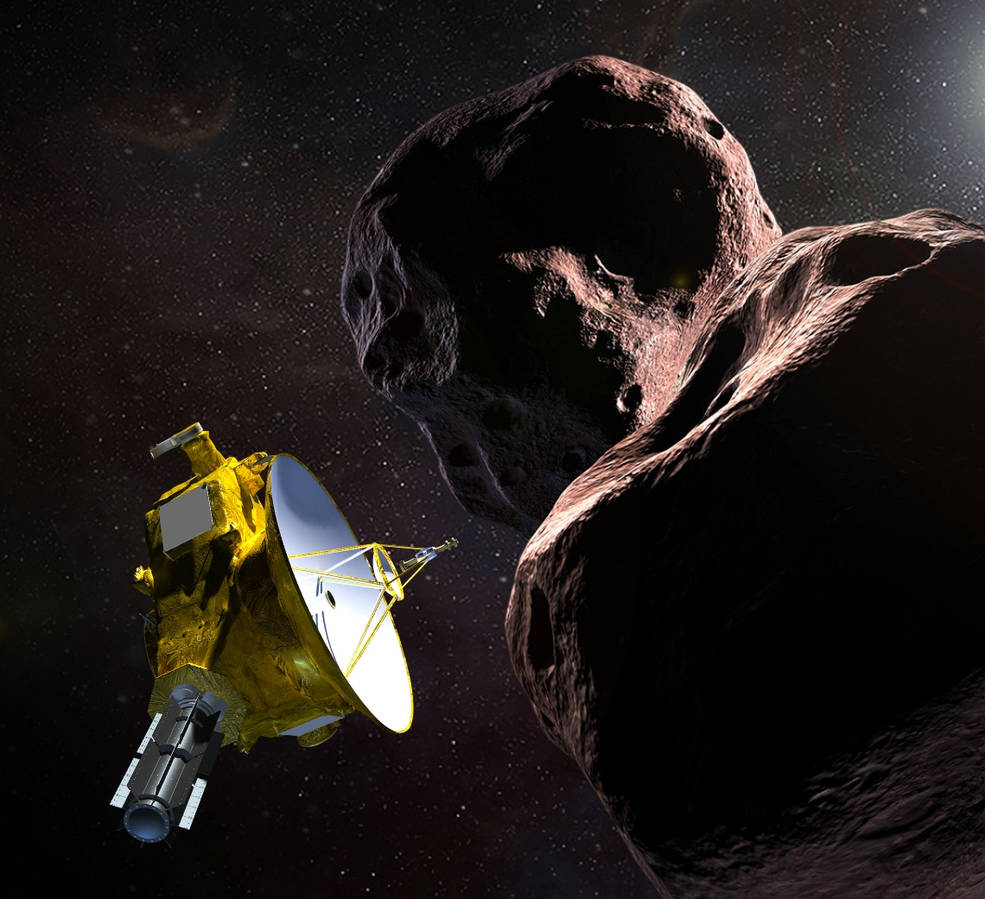

On New Year's Day (Jan. 1), New Horizons will fly by the distant object Ultima Thule in the Kuiper Belt, a realm of icy objects at the edge of the solar system that includes Pluto. The flyby is a second for New Horizons, which flew by Pluto in July of 2015, and will mark the first-of-its-kind close look at a Kuiper Belt object forged during the birth of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago.

"It's electric, across the whole team," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) said in short flyby preview webcast today (Dec. 28) on YouTube and Facebook Live hosted by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel Maryland. JHUAPL oversees the New Horizons mission for NASA. "The people are ready. We can't wait to go exploring."

Because of a partial U.S. government shutdown that began Dec. 22, some of NASA's public outreach feeds were initally silenced. JHUAPL has taken over mission briefings (like today's webcast) and will provide live updates via the JHUAPL YouTube page for flyby events on Monday and Tuesday (Dec. 31 and Jan. 1). You can see a full schedule here.

Today, NASA began carrying the JHUAPL briefings on its NASA.gov/live page and posting Twitter announcements via @NASANewHorizons and other accounts. But the agency's website continues to point visitors to JHUAPL for the latest mission updates and photos.

"The primary effect has been a loss of NASA public affairs, which has made our public engagement much more challenging," Stern told Space.com in an email. But, he added, the mission team isn't distracted. "We're focused."

That focus is key because Stern and the New Horizons team are attempting something that's never been done before: the farthest flyby of an an object in history, a record last set by the same team in 2015 at Pluto.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ultima Thule — officially known as 2014 MU69 — is 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers) from Earth. That's about 1 billion miles beyond Pluto, Stern said in the webcast.

If all goes well, New Horizons will zip by Ultima Thule on New Year's Day at 12:33 a.m. EST (0533 GMT) at a whopping 32,000 mph (51,500 km/h). At its closest point, New Horizons will be 2,200 miles (3,540 km) from Ultima Thule. That's about the distance between Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., with Ultima Thule appearing about as large to New Horizons as the full moon does to observers on Earth, Stern said.

The stakes are high. It takes 6 hours and 8 minutes for a signal to reach Earth from New Horizons. A roundtrip for a signal is just over half a day: 12 hours and 15 minutes. So New Horizons will have to work on its own during the actual rendezvous, just as it did at Pluto.

"Because this is a flyby mission, you only get one chance to get it right," Alice Bowman, mission operations manager for New Horizons, said in the webcast.

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft launched on its initial mission to Pluto in 2006, making a flyby of the dwarf planet on July 14, 2015. A year before that historic encounter, astronomers discovered Ultima Thule, giving the mission team a tantalizing second target to visit.

"Very few teams have had this experience and this privilege of crossing the entirety of our solar system on a mission," Stern said in the webcast. "Really only the Pioneers and the Voyagers that came before us."

Not a lot is known about Ultima Thule. It is much smaller than Pluto, but its exact size and shape are unknown. It may have a reddish tint, but it isn't reflecting light like scientists initially expected, raising eyebrows ahead of Tuesday's flyby.

"We don't have a lot of information on the composition," said mission co-investigator Kelsi Singer of SwRI. "That's one of the things we're really excited to learn."

That reddish tint of Ultima Thule? Scientists aren't sure what causes that either, Singer added.

Stern said any new discoveries from Ultima Thule will help unlock mysteries of the solar system's history.

"This is a time capsule that we've never seen before that's going to take us back four and a half billion years to the birth of the solar system," he added.

Editor's note: This story was updated Dec. 29 to include the correct description of the Kuiper Belt region, which includes Pluto, and the correct flyby speed of 32,000 mph.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.