Asimov's Sword: Excerpt from 'Astounding' History of Science Fiction

Alec Nevala-Lee was born in Castro Valley, California, and graduated from Harvard College with a bachelor's degree in classics. He is the author of three novels, including "The Icon Thief," and his stories have been published in Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Lightspeed Magazine, and The Year's Best Science Fiction. His nonfiction has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The Daily Beast, Salon, Longreads, The Rumpus, and the San Francisco Bay Guardian. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oak Park, Illinois.

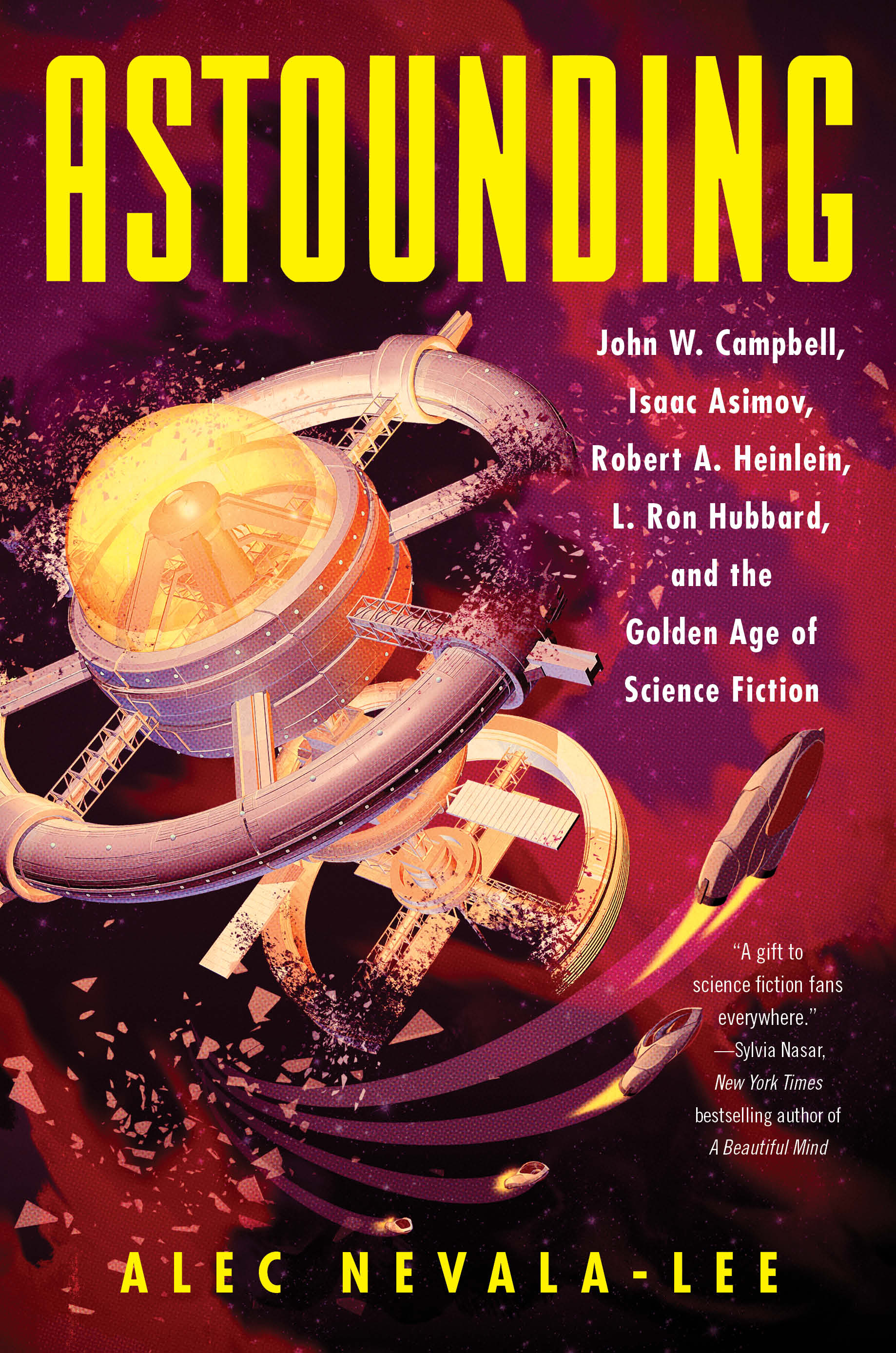

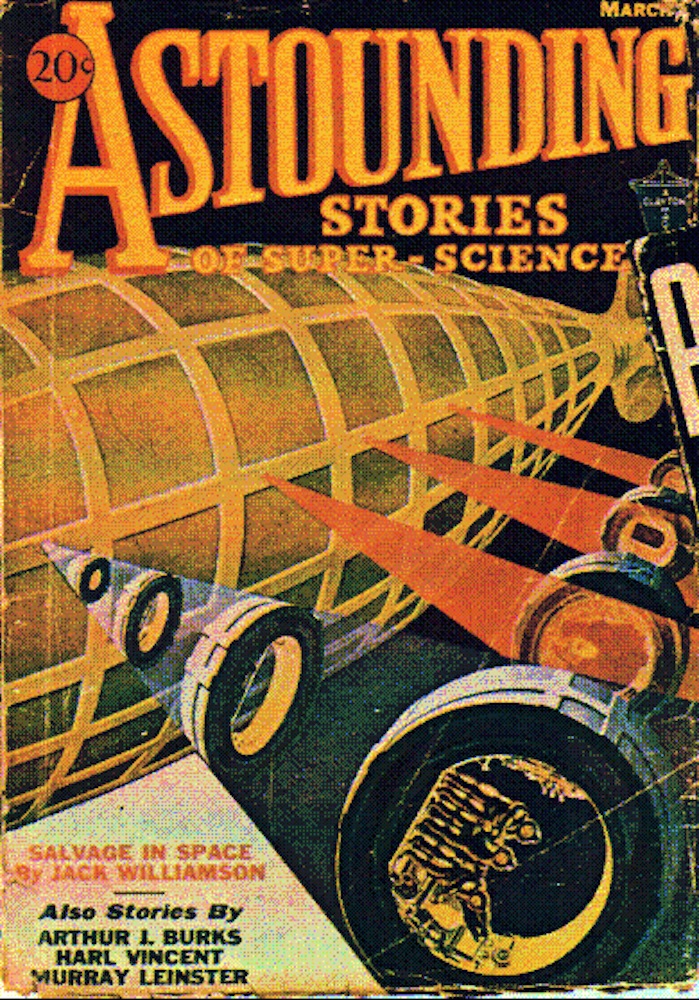

Nevala-Lee's latest book "Astounding," out today (Oct. 23), chronicles the interwoven lives of four science fiction titans: Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard and the editor of all four of them at the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, John Campbell. Read a Q&A with Nevala-Lee on the new book here.

Below, you can read an excerpt from the book's prologue. [A Space.com Science Fiction Reading List]

ASIMOV'S SWORD

My feeling is that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required. . . . Nevertheless, a meeting of such people may be desirable for reasons other than the act of creation itself. . . . If a single individual present . . . has a distinctly more commanding personality, he may well take over the conference and reduce the rest to little more than passive obedience. . . . The optimum number of the group would probably not be very high. I should guess that no more than five would be wanted.

—ISAAC ASIMOV, "ON CREATIVITY"

On June 13, 1963, New York University welcomed a hundred scientists to the Conference on Education for Creativity in the Sciences. The gathering, which lasted for three days, was the brainchild of the science advisor to President John F. Kennedy, who had pledged two years earlier to send a man to the moon. America was looking with mingled anxiety and anticipation toward the future, which seemed inseparable from its destiny as a nation. As the event's organizer said in his introductory remarks, the challenge of tomorrow was clear: "That world will be more complex than it is today [and] will be changing more rapidly than now."

One of the attendees was Isaac Asimov, an associate professor of biochemistry at Boston University. At the age of forty-three, Asimov was not quite the celebrity he later became — he had yet to grow his trademark sideburns — but he was already the most famous science fiction author alive. He was revered within the genre for the Foundation trilogy and the stories collected under the title I, Robot, but he was better known to general readers for his works of nonfiction. After the launch of Sputnik in 1957, Asimov had been awakened to the importance of educating the next generation of scientists, and over the course of thirty books and counting, he had reinvented himself as the world's best explainer.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The day before the conference, Asimov had taken a bus from Boston to New York. It was a trip of over four hours, but he was afraid of flying, and he welcomed the chance to get out of the house — he was going through a difficult period in his marriage. On the morning of his departure, the papers carried photographs of the death of the Vietnamese monk Thích Qua'ng Đúc, who had set himself on fire in Saigon, and coverage of George Wallace, who had blocked a doorway at the University of Alabama to protest the registration of two black students. Just after midnight on June 12, the civil rights activist Medgar Evers had been shot in Mississippi, although his murder would not be widely reported until later that afternoon.

Asimov followed the news closely, but on his arrival in New York, he was more concerned by the loss of a bankroll of two hundred dollars that he was carrying as emergency cash — "I just dropped it somewhere." It left him distracted throughout the conference, and afterward, he remembered almost nothing about it. What he recalled most clearly was a discussion of the basic problem facing the scientists who had gathered there, which was how to identify children who had the potential to affect the future. If you could spot such promising students, you could give them the attention they needed while they were still young — but you had to find them first. [Gallery: Visions of Interstellar Starship Travel]

It was a question of obvious significance, and it had particular resonance for Asimov. He had always thought of himself as a child prodigy — he had mixed feelings about entering middle age, noting that "there is no possibility of pretending to youth at forty" — and his life had been radically transformed by a mentor who had found him at just the right time. At the conference, he proposed what he felt was a practical test for recognizing creative youngsters, but no one else took it seriously.

Two days after returning home to West Newton, Massachusetts, Asimov was asked to write an article for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the journal best known for its Doomsday Clock, a visual representation of the risk of nuclear war that currently stood at seven minutes to midnight. Asimov, who was deeply concerned by the bomb, decided to return to the idea that he had raised in New York. He went to work, typing away in his attic office, which had become a refuge from his unhappy personal life — his wife was talking openly about divorce, and he was worried about their son David, who seemed to have nothing in common with his famous father.

Asimov began his essay, "The Sword of Achilles," with an episode from the Trojan War. The Greeks desperately wanted to recruit the warrior Achilles, but his mother, Thetis, feared that he would die at Troy. To protect her son, she sent him to the island of Scyros, where he dressed as a woman and concealed himself among the ladies of the court. The clever Odysseus arrived in the guise of a merchant, laying out clothing and jewelry for the maidens to admire. Among the other goods, he hid a sword. Achilles seized and brandished it, giving himself away, and after being identified, he was persuaded to go to war.

"Wars are different these days," Asimov continued. "Both in wars against human enemies and in wars against the forces of nature, the crucial warriors now are our creative scientists." It was a technological vision of American supremacy that Asimov had carried over from World War II, and it was about to be tested in Vietnam. For now, however, he only noted that while it was necessary to provide gifted students with ways to develop their creativity, it was too impractical and expensive to lavish the same resources on everyone.

"What we need is a simple test, something as simple as the sword of Achilles," Asimov wrote. "We want a measure that will serve, quickly and without ambiguity, to select the potentially creative from the general rank and file." He then outlined what he saw as a useful method for finding the innovators of tomorrow. It was elegant and straightforward, and in the events of his own remarkable life, Asimov had witnessed its power firsthand: "I would like to suggest such a sword of Achilles. It is simply this: an interest in good science fiction."

From ASTOUNDING by Alec Nevala-Lee, published by Dey Street Books. Copyright © 2018 by Alec Nevala-Lee. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers. You can buy "Astounding" on Amazon.com.

Follow us on Twitter@Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.