Ancient Mars Lakes & Laser Blasts: Curiosity Rover's 10 Biggest Moments in 1st 5 Years

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Introduction

On the night of Aug. 5, 2012, NASA's most ambitious Mars rover to date pulled off a harrowing sky-crane landing inside the Red Planet's 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater.

Within weeks, the six-wheeled Curiosity rover had found signs of an ancient streambed, further bolstering suspicions that microbes may have been able to survive on Mars in the ancient past. Within months of touching down, the rover had made measurements suggesting that radiation on Mars would not be a showstopper for crewed missions to the Red Planet.

And then Curiosity just kept rolling along. The rover has made its way through Gale Crater's plains and into the foothills of the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 km) Mount Sharp, putting more than 10.5 miles (17 km) on its odometer to date. Curiosity continues to gather data that should further flesh out scientists' understanding of ancient Mars and the planet's potential to support life. Here are some of the highlights of Curiosity's journey. [Amazing Mars Photos by NASA's Curiosity Rover (Latest Images)]

Launch

Curiosity was originally scheduled to lift off in 2009, but delays pushed things back two years. The rover had a flawless launch on Nov. 26, 2011, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, riding a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket to space. An estimated 13,500 people watched the liftoff from NASA's nearby Kennedy Space Center, with many others viewing from surrounding areas. NASA officials also joined in the excitement.

"It is absolutely a feat of engineering, and it will bring science like nobody's ever expected," Doug McCuistion, head of NASA's Mars exploration program at the time, said of Curiosity shortly after the launch. "I can't even imagine the discoveries that we're going to come up with."

Landing

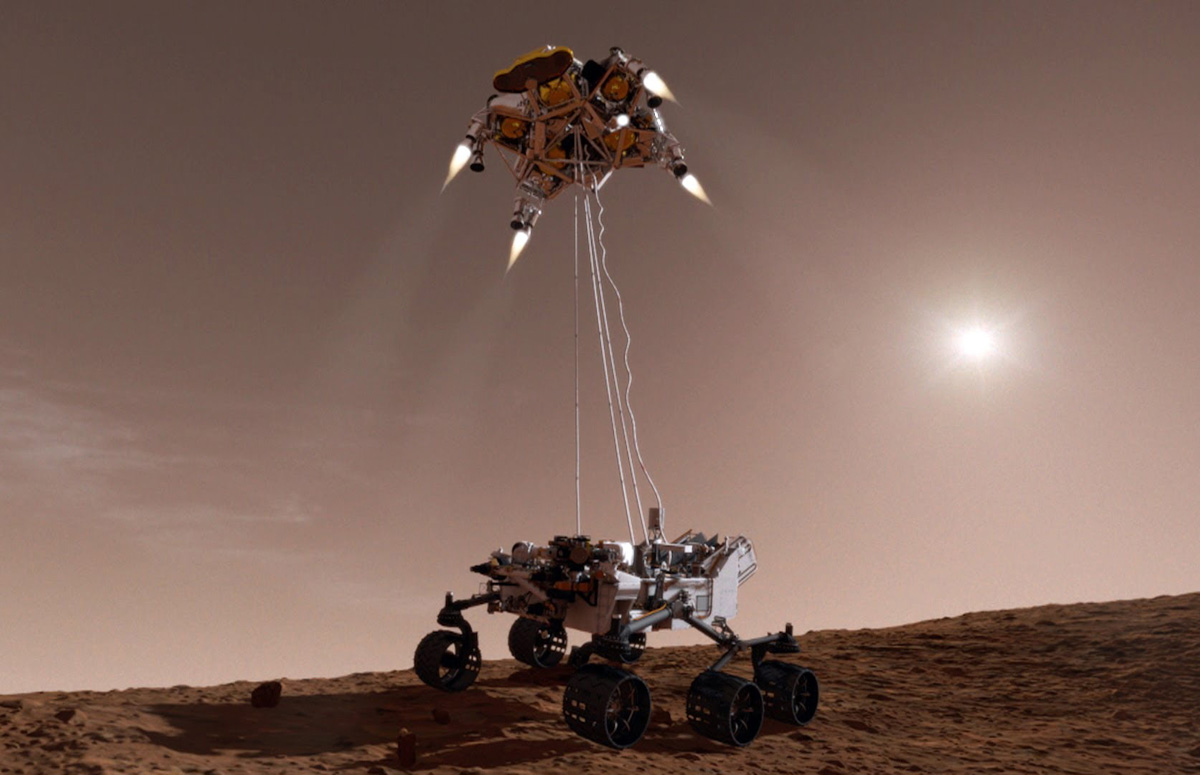

After traveling more than 352 million miles (566 million km) through space, Curiosity landed safely inside Gale Crater on Aug. 5, 2012 (Pacific Time). The rover settled down within driving distance of its ultimate destination: Mount Sharp, which is known more formally as Aeolis Mons. This touchdown was no easy feat. Curiosity was the first to ride a rocket-powered sky crane to the Martian surface; the crane then cut itself loose and crash-landed deliberately a safe distance away, to protect the rover.

Mission control at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, erupted in cheers as Curiosity beamed home the news that it had survived its "7 minutes of terror" Martian arrival. Those cheers were echoed by millions of people around the world, who were following the landing live online.

"We're on Mars again," then-NASA chief Charlie Bolden said minutes after Curiosity's arrival. "It doesn't get any better than this."

First panorama on Mars

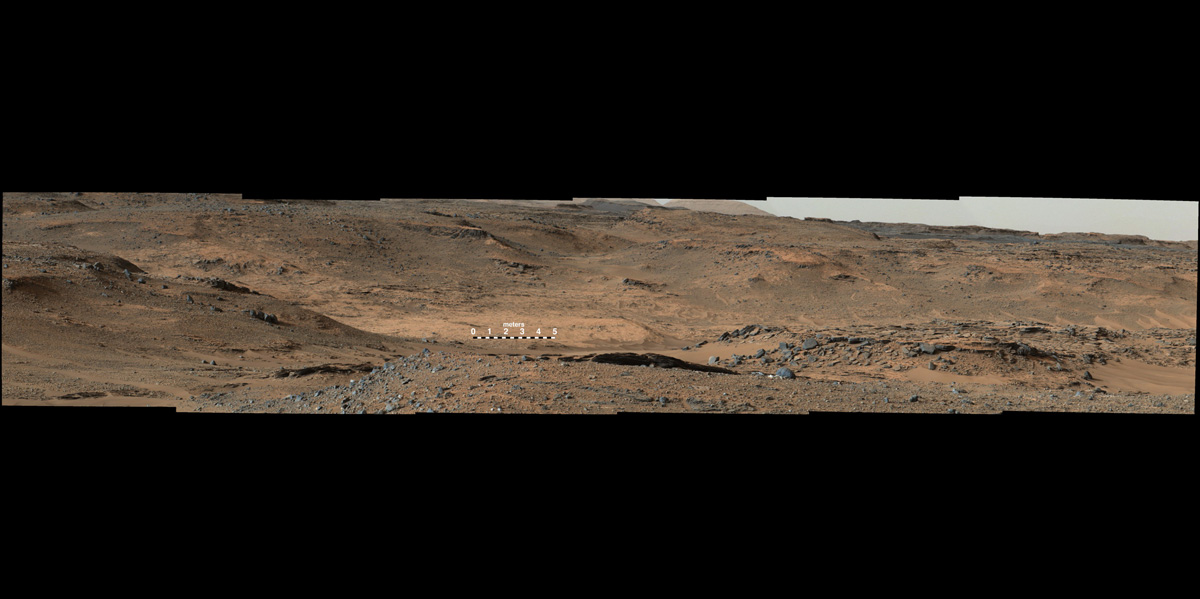

Curiosity sent back its first panorama from the surface of Mars just a few days after landing. The 360-degree image was stitched together from thumbnail images taken by the rover's Mast Camera.

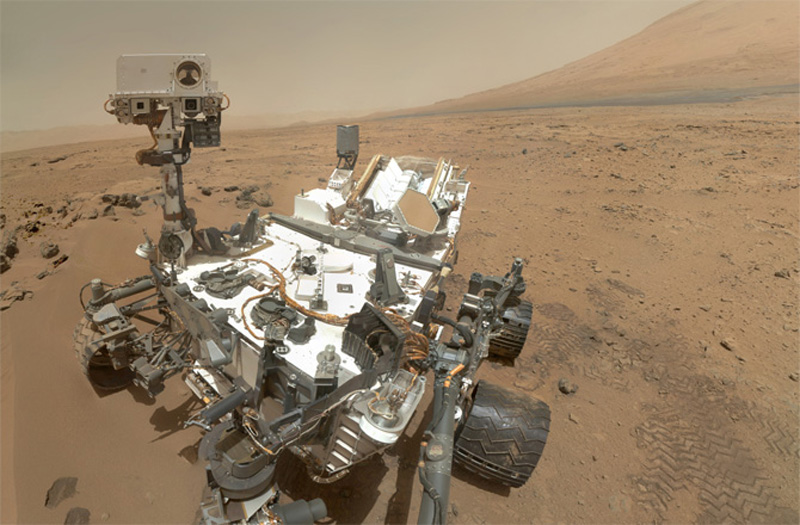

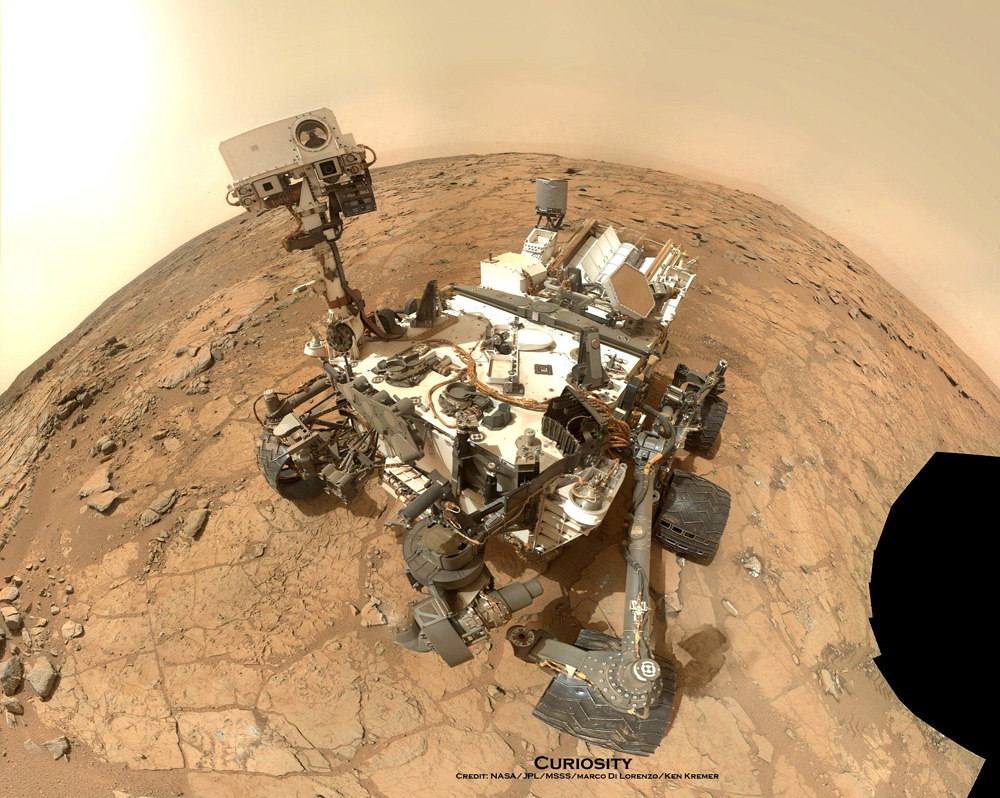

The panorama only hinted at the amazing pictures Curiosity would produce in the following months and years. Periodically, the team directs Curiosity to take "selfies" using its Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI). These pictures not only show spectacular vistas surrounding the rover but also help team members monitor how the rover is doing. (The wheels have been a bit troublesome over the years; the rough Martian terrain initially chewed the wheels up faster than mission controllers had anticipated. As a result, Curiosity's handlers have directed the rover to travel over softer, more forgiving ground whenever possible.)

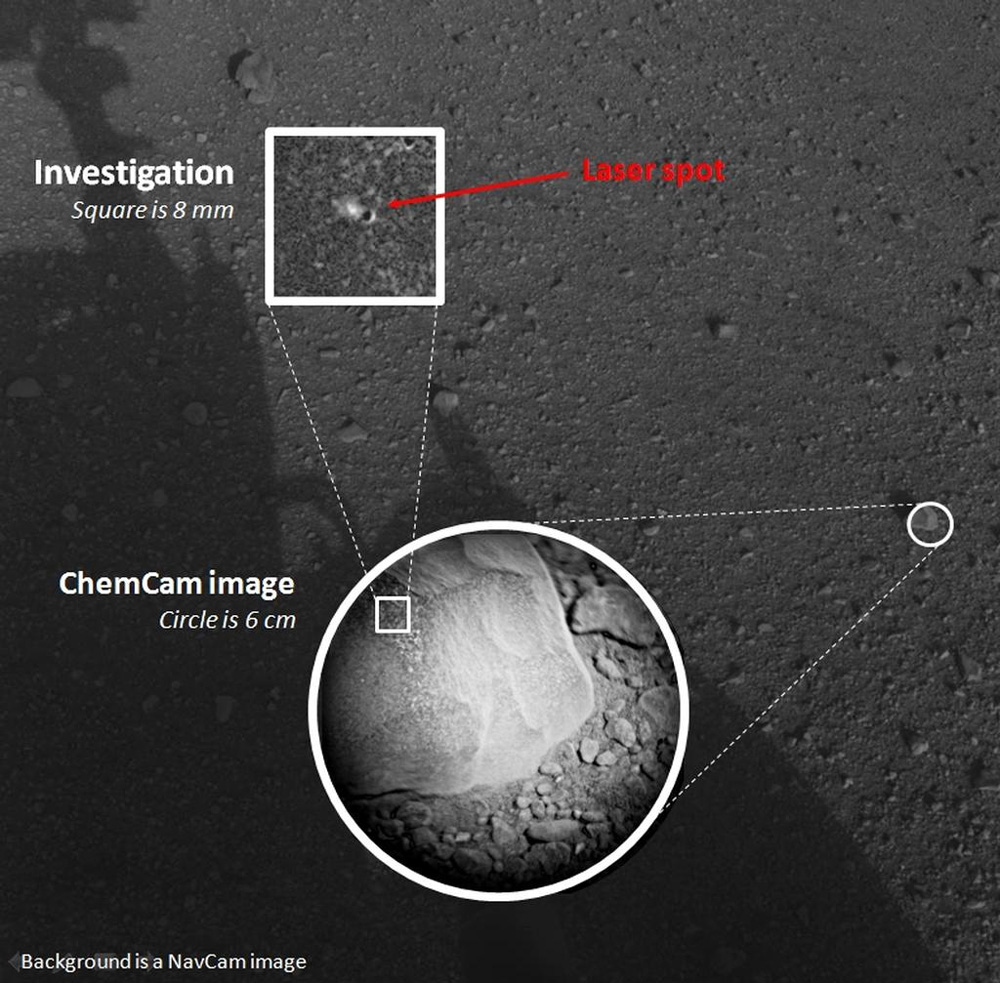

First laser firing

Curiosity's famous laser instrument, known as ChemCam, got its first test in August 2012, just weeks after the landing. ChemCam fired at a rock dubbed "Coronation," shooting 30 laser pulses in 10 seconds. The first shots were intended as just practice, but later laser shots allowed Curiosity to look at the elemental composition of the rock.

"We got a great spectrum of Coronation — lots of signal," ChemCam lead scientist Roger Wiens, of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, said in a statement at the time. "Our team is both thrilled and working hard, looking at the results. After eight years building the instrument, it's payoff time!"

Discovery of a habitable environment

Curiosity made a major find only weeks after landing, when it discovered evidence of an ancient streambed that could have had hip-deep water in places. Photos taken by the rover indicated that some stones were large and round, meaning that water could have transported them over long distances.

"Plenty of papers have been written about channels on Mars, with many different hypotheses about the flows in them," Curiosity co-investigator William Dietrich, of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement at the time. "This is the first time we're actually seeing water-transported gravel on Mars. This is a transition from speculation about the size of streambed material to direct observation of it."

First rock drilled

In February 2013, Curiosity passed its first major drill test: It created a small hole just 0.8 inches (2 centimeters) deep in a Martian rock nicknamed "John Klein." The images showed that the drill created a perfect circle, surrounded by debris from the instrument. While this was billed as a test, NASA did pick a rock that had evidence of an ancient wet environment.

"Pre-drilling observations of this rock yielded indications of one or more episodes of wet environmental conditions," mission managers said in a statement at the time. "The team plans to use Curiosity's laboratory instruments to analyze sample powder from inside the rock to learn more about the site's environmental history."

Curiosity's drilling, however, stalled in December 2016, when the drill-feed mechanism stopped working properly. The mechanism is supposed to move the drill forward and backward, and NASA is still working on a solution to this failure after more than seven months.

"Instead of using the feed mechanism to drive the bit into the rock, we may be able to use motion of the arm to drive the bit into the rock," Curiosity deputy project manager Steve Lee, of JPL, said in a statement this July.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

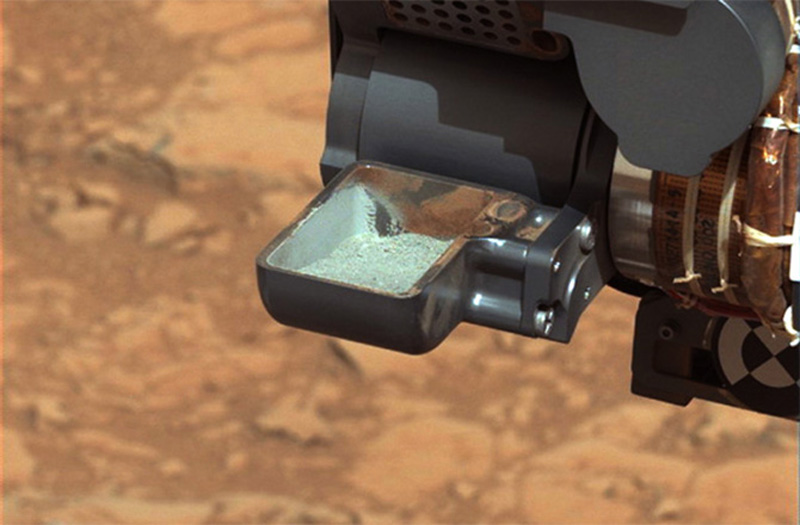

First use of SAM/CheMin

Ancient microbial life could have lived on Mars, scientists concluded after Curiosity analyzed the first sample from the interior of a Red Planet rock. Using another drilled sample from "John Klein," the rover's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) and Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instruments found many of the ingredients of life in the powder: nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, sulfur, phosphorous and carbon.

"Mars has written its autobiography in the rocks of Gale Crater, and we've just started deciphering that story," Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA's Mars Exploration Program at the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C., said at the time.

Analysis of additional drilled samples later revealed that Gale Crater likely hosted a potentially habitable lake-and-stream system for millions of years in the ancient past.

Measuring radiation for a human mission

Curiosity is also helping NASA's efforts to put astronauts on Mars. Measurements from the rover's Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) instrument released in 2013 suggest that a human would receive 1.01 sieverts of radiation during an 860-day Mars mission (consisting of an 180-day flight to the planet, 500 days on the Martian surface and another 180-day flight back).

By comparison, the European Space Agency limits its astronauts' lifetime exposure to 1 sievert, a dose that causes a 5 percent increase in lifetime risk of fatal cancer. NASA currently caps the risk limit at 3 percent, but adjustments could be made to accommodate trips outside of low Earth orbit. "It's certainly a manageable number," said RAD principal investigator Don Hassler of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, lead author of the study.

Discovering its first meteorite

Not every rock Curiosity has encountered is from Mars. In July 2014, NASA announced that the rover found a 7-foot-wide (2 meters) rock that scientists nicknamed "Lebanon." Nearby were two smaller companions. Curiosity used ChemCam and its Remote Micro-Imager camera to take detailed images of the biggest rock, finding strange cavities in the surface.

"Heavy Metal! I found an iron meteorite on Mars," Curiosity's handlers wrote via Twitter (@MarsCuriosity) at the time.

Arrival at Mount Sharp

Curiosity made it to the foothills of Mount Sharp, its chief science destination, in September 2014.

"It's really an honor and a privilege for me to be able to tell you all that we have finally arrived at the far frontier that we have sought for so long," Curiosity project scientist John Grotzinger, Curiosity's project scientist at the time, said during a news conference in September 2014.

For the last three years, Curiosity has been exploring the various layers on Mount Sharp to see how the mountain changed over geological time, and whether it also harbored habitable environments in the ancient past. Recently, the rover moved to a new ridge and is comparing that environment to the layer below it. So far, the rover has seen some sand dunes and found further evidence of ancient freshwater deposits.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.