Curiosity Rover's Drill Still Wonky on Mars, 7 Months Later

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

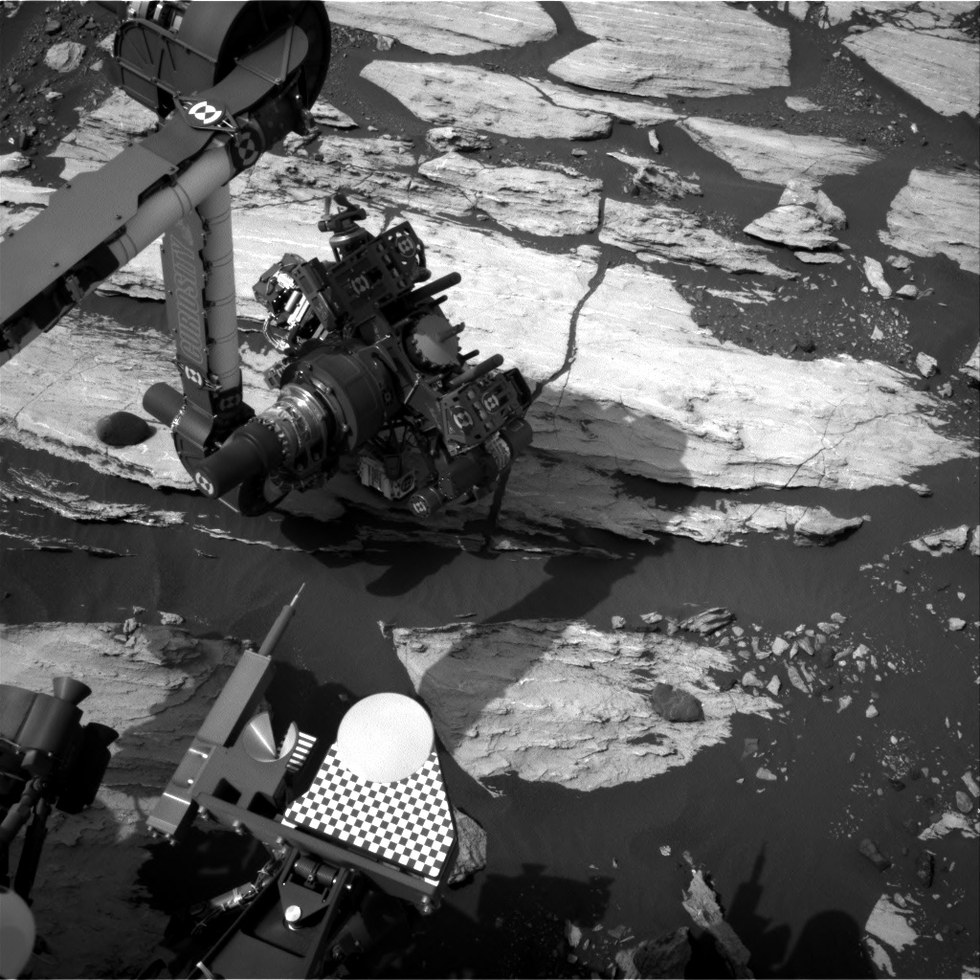

More than seven months after a malfunction sidelined the rock-boring drill aboard NASA's Curiosity Mars rover, mission team members are still trying to find a solution, or a work-around.

On Dec. 1, 2016, Curiosity detected a problem with its drill feed mechanism, which moves the drill at the end of the rover's 7-foot-long (2.1 meters) robotic arm forward and backward. The car-size robot hasn't drilled any rocks since then.

Rover engineers haven't given up hope of fixing the mechanism, but they're also now investigating new and inventive ways to drill, NASA officials said.

"Instead of using the feed mechanism to drive the bit into the rock, we may be able to use motion of the arm to drive the bit into the rock," Curiosity deputy project manager Steve Lee, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a statement.

Other possible strategies include drilling without the two small posts that Curiosity normally places against a rock, one on each side of the bit, for stability during drilling operations, Lee added.

Mission engineers are also looking at different ways of delivering the powder collected during drill operations to instruments on Curiosity's body — for example, by using the robotic arm's soil scoop, NASA officials said.

This isn't the first time a drill issue has afflicted Curiosity. For example, the rover experienced intermittent short circuits in the drill's hammering mechanism several times over the past few years.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Curiosity has drilled into 15 different rocks since landing inside Mars' 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater in August 2012. Analyses of these drilled samples have been key to the $2.5 billion mission's biggest discoveries, including the determination that Gale hosted a potentially habitable lake-and-stream system billions of years ago.

Since September 2014, Curiosity has been climbing through the foothills of Mount Sharp, which towers 3.4 miles (5.5 km) into the Martian sky from Gale's center. The six-wheeled rover is studying the various rock layers as it goes, looking for clues about Mars' transition from a warm and wet world in the ancient past to the cold, dry planet it is today.

Curiosity's current work is focused on Vera Rubin Ridge, a 4-mile-long (6.4 km) landform on the lower northwest flank on Mount Sharp. Mission team members informally named the ridge after astronomer Vera Cooper Rubin, who died last year at the age of 88.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.