Breakthrough Starshot's Interstellar Sail Works Best As a Ball

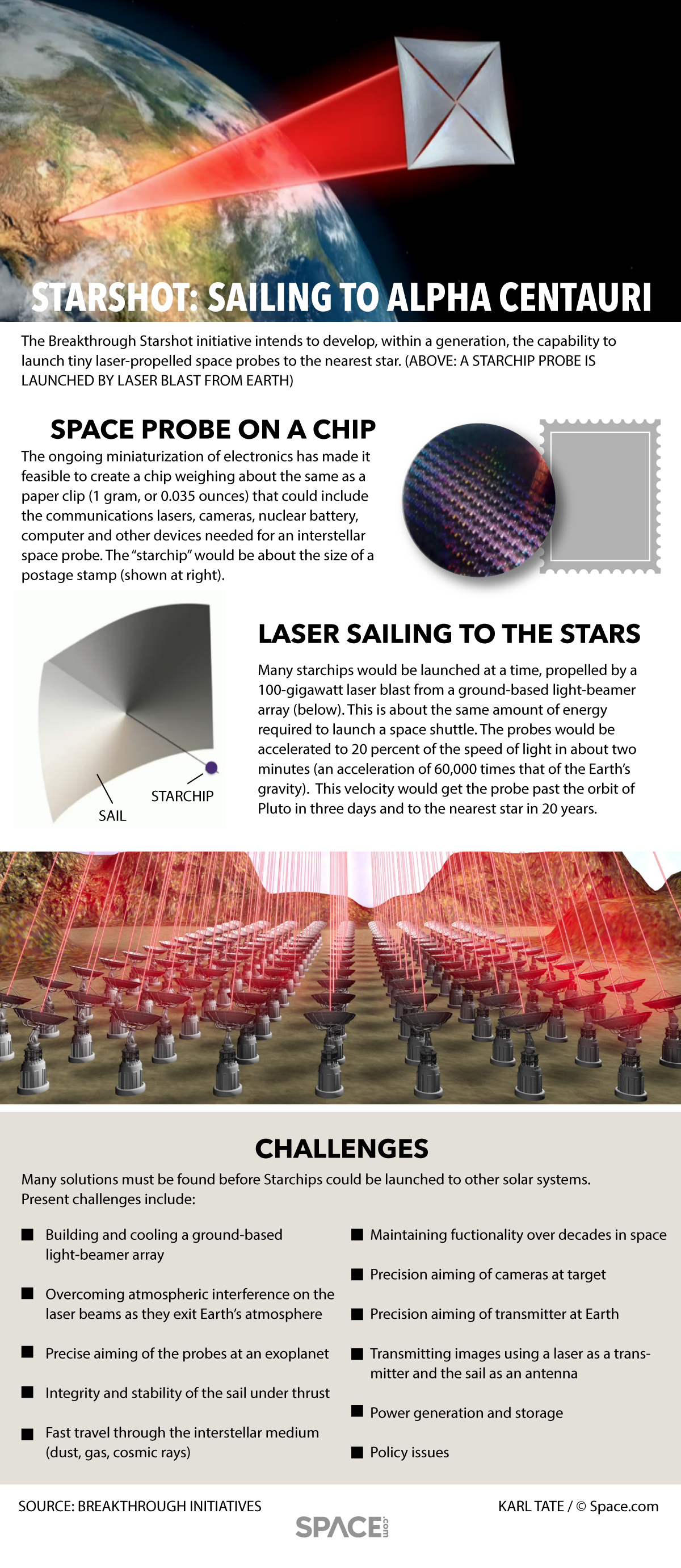

The Breakthrough Starshot initiative, announced last year, has one very ambitious goal: to use high-powered lasers to launch a tiny, lightweight space probe toward our solar system's nearest star, Alpha Centauri, which is located roughly 4 light-years away.

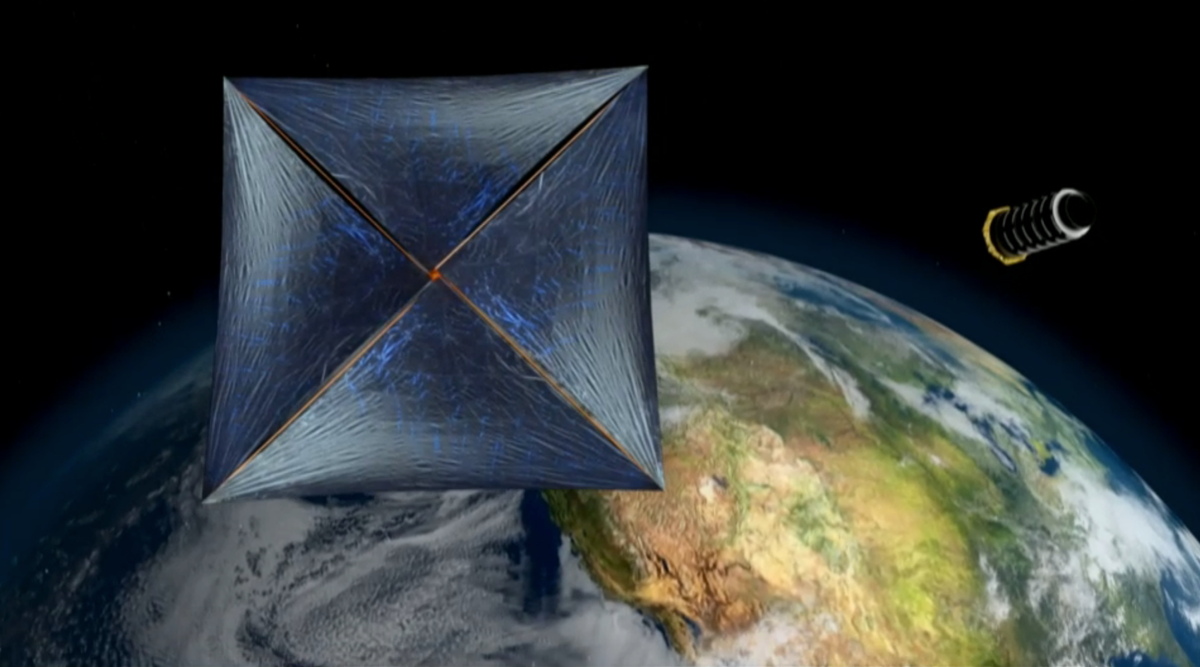

Until now, illustrations depicting this concept show the probe tethered behind a parachute-shaped sail launched into interstellar space by a single, but powerful, laser beam.

But new research indicates that this design is too unstable. If the parachute tilts even a little bit, it could fly off the beam — and way off course — dragging the probe along with it, the scientists say.

The optimal design? A tiny ball nestled among four laser beams. Breakthrough Starshot team member Zachary Manchester, a postdoctoral fellow in Harvard University's Agile Robotics Lab; and Avi Loeb, chair of both the Harvard University Astronomy Department and the Breakthrough Starshot advisory committee, published their findings in the March 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters. [How Breakthrough Starshot Will Work]

The analysis shows that even if the spherical probe were to roll around a little bit, the energy from the laser beams would keep it contained and prevent it from flying off into space. There's another advantage, too.

"One of the nice things about that is that you could think about putting all of the electronics inside the sphere and then they'll be nicely shielded from the beams," Manchester told Space.com.

This means the sail and the probe would be one unit, as opposed to the previous design of a flat sail towing a postage-stamp-size probe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are many challenges to address before the Starshot can become a reality, and Manchester noted two such challenges related to the ball and the laser beams. First, the ball has to be very lightweight and extremely reflective.

"If it absorbs too much of the laser power, if it's not shiny enough, it'll cook, because there's so much power coming from the laser," Manchester said.

Secondly, getting four powerful laser beams to line up perfectly is no easy task. The lasers would be beamed — not from four individual instruments, but from an array of hundreds of machines that combine their beams to produce the power to launch the probe.

To produce enough power, the beams need to be lined up, or in phase. That's tricky to do because the wavelength of light that makes up a laser is very small, on the order of microns.

But with $100 million to strategically invest in these different areas, the Breakthrough Starshot team members think they can solve these problems and others. [Breakthrough Starshot in Pictures]

"Everyone is hoping that 20 years is the right number," Manchester said. "If there's enough investment in the right areas now, in 20 years, we'll be able to do something."

But one question still nagged: If the craft is a ball, can we still call it a sail?

Manchester said yes. "It's still a sail in the sense that it's getting pushed by the laser," he said.

You can follow Tracy Staedter at her website tracystaedter.com and @tracy_staedter. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Tracy Staedter is a freelance science writer, editor, writing coach, and consultant with an eclectic career spanning over 20 years. She's has covered a range of science and technology stories from astrophysics to zero waste. She worked on staff for such online sites and publications as Space.com, LiveScience.com, Astronomy, Scientific American Explorations, MIT Technology Review, DNews, and Seeker. She also wrote the illustrated book, Rocks and Minerals (part of the Reader’s Digest Pathfinders series) and founded the Fresh Pond Writers workshop for fiction and creative nonfiction writers.