Dwarf Planet Ceres Camouflaged by Asteroid Dust

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

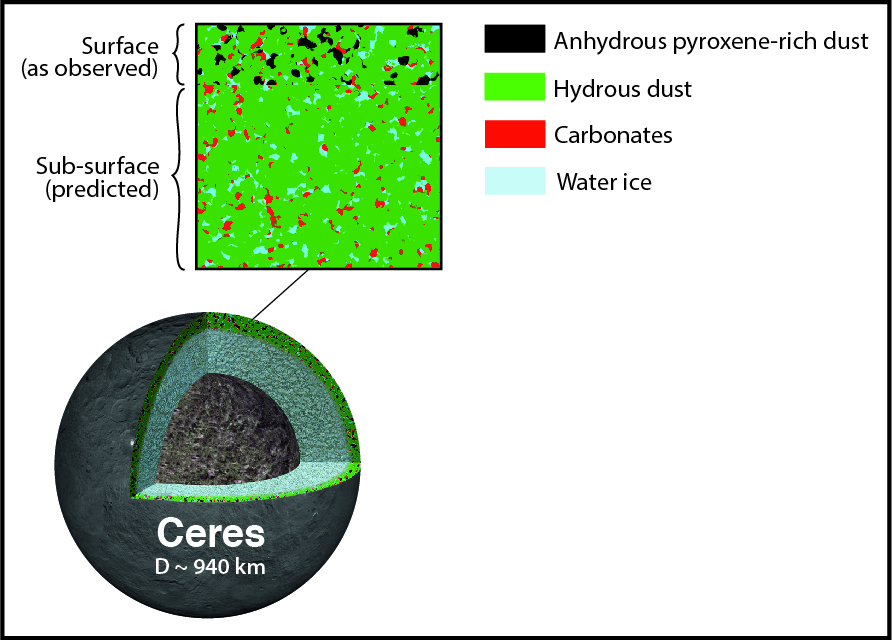

The dwarf planet Ceres is cloaked in a layer of asteroid dust that disguises its true surface composition, a new study suggests.

Data gathered by ground-based telescopes and NASA's Dawn spacecraft, which has been orbiting Ceres for nearly two years, indicate that the dwarf planet's surface harbors lots of water-bearing minerals, such as carbonates and clays.

But that's not exactly what astronomers saw when they studied Ceres using NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), a modified Boeing 747 jet that carries a 100-inch-wide (2.5 meters) telescope. [Awesome Photos of Dwarf Planet Ceres]

"We find that the outer few microns of the surface is partially coated with dry particles," study co-author Franck Marchis, a senior planetary astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, said in a statement. "But they don't come from Ceres itself. They're debris from asteroid impacts that probably occurred tens of millions of years ago."

These "interplanetary dust particles," which often blaze up as meteors when they hit Earth's atmosphere, are known to accumulate on the surfaces of smaller asteroids in deep space, the researchers said. And it now appears that they also build up on the 590-mile-wide (950 kilometers) Ceres, the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

"This study resolves a longtime question about whether asteroid surface material accurately reflects the intrinsic composition of the asteroid," study lead author Pierre Vernazza, a research scientist in the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille (LAM–CNRS/AMU), said in the same statement.

"Our results show that, by extending observations to the mid-infrared, the asteroid's underlying composition remains identifiable despite contamination by as much as 20 percent of material from elsewhere," Vernazza added.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new Ceres observations are not the only evidence that the surfaces of large cosmic bodies can be affected by foreign material. For example, NASA's New Horizons probe spotted a reddish cap on Pluto's largest moon, Charon, during the spacecraft's epic flyby of the dwarf planet in July 2015. New Horizons team members think this cap formed after methane that once swirled in Pluto's atmosphere was trapped at Charon's poles and was then exposed to high-energy radiation.

The $467 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007. The probe orbited Vesta, the asteroid belt's second-largest resident, from July 2011 through September 2012, when it departed for Ceres. Dawn reached Ceres in March 2015 and has been studying the dwarf planet from orbit ever since.

The new study was published last week in The Astronomical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.