Forecasting the Future is Becoming Big Business for Sci-Fi

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The future is not that far off, and many professional forecasters in Washington make a living out of predicting the kind of world we might inhabit 10, 20 or 30 years down the road.

These reports are put together by a committee of dozens of experts, each contributing their best-case (or worst-case) scenarios in politics, society, technology, science and the environment. Governments and companies often use such reports to make decisions about where to invest money, station troops, open factories and how to train future workers. But now thinkers believe that sketching out fictional futures may do more to stimulate people to prepare for the future than multi-chapter white papers with hundreds of footnotes.

Two recent studies — the National Intelligence Council's "Global Trends: Paradox of Progress" and the Atlantic Council's "Global Risks 2035: The Search for the New Normal" — both look at the year 2035.

They each paint somewhat similar views of a future in which the United States has become more inward looking; Russia, China and Iran have become more aggressive in asserting regional power; and technology is moving fast, although not everybody is keeping up. Global economic growth will continue to be weak and uneven, the reports suggest, while people will continue to flock to megacities of 10 million or more, swelling the number of such metropolises from 28 in 2014 to 41 in 2030.

The reports were released within weeks of Donald Trump's inauguration as president — an occasion that nobody predicted 18 months ago, let alone 10 or 20 years ago.

RELATED: Future Robots Could Have Wall-Climbing Gecko Feet

The Atlantic Council presented several fictional scenarios of the future written in part by August Cole, a senior non-resident fellow and the author of "Ghost Fleet," a near-future military thriller published last year about a U.S.-China conflict in the Pacific.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cole said that storytelling is sometimes more effective than graphs and trend-line charts.

"We felt that was an effective way to show vs. tell. We were trying to show the future," he said. "Also to see what kind of things writers might come up with as opposed to pure policy or security analysis."

Cole solicited contest entries as part of the Atlantic Council's The Art of the Future Project, which aims to use renderings of the future "to inform official perspectives on emerging international security issues." Entries used the information collected by the analysts. The winner was "Fingers on the Scale," a short story about a new tracking app that allows parents to boost their children's academic achievement, and which becomes a favorite of rulers of despotic nations. The CIA intervenes, purposefully limiting the abilities of the despots' children and preventing other countries from developing the intellectual caliber of their elites.

A similar contest sponsored by the council and the U.S. Marine Corps produced three short stories about, respectively: a squadron of Marines fighting terrorists and robots in a drought-stricken African nation; a fictional raid on a Moroccan terror camp; and a domestic crisis brought on by a genetically engineered bio-weapon in corn seed.

Cole says that he looks at future forecasting from the perspective of a political, military or corporate leader.

"It better be fun to read, it better be engaging," he said. "It might not be popular, but it's incumbent that you're telling a story that's compelling."

Some companies are jumping on the future-fiction bandwagon. The credit card firm Visa hired LA-based SciFutures to set up a future store in San Francisco's Embarcadero district where payments are "frictionless" and customers are scanned without the need for a register.

RELATED: 3D-Printed Future Human Shows How Our Joints Will Evolve

The same consulting company also helped the home improvement chain Lowe's set up a virtual reality station for customers of the company's home remodeling center.

"We use the content [of future reports] as our raw material," said Ari Popper, founder and CEO of SciFutures. "It's hard to get meaningful action out of a 600-page report. But if you can use the science and trends and turn it into some engaging content — that's what storytelling is — you are much more likely to inspire people and get them to take action."

Popper uses contract science fiction writers and pairs them with business clients to imagine what the world might look like, and how the companies can position themselves for the future.

He recently worked with members of NATO to develop a "more emotional and visceral" sense of where the future geopolitical world will look like in 10 or 15 years.

Despite all the forecasting, neither Cole nor Popper pretend that their current predictions of the future will be correct.

"We're not in the business of getting it right, but getting folks to do things differently," Popper said. "Organizations have a hard time getting out of their own way. Our job is to inspire them and appreciate what's possible in way that leads to action. They're creating their own future rather than being a victim of it."

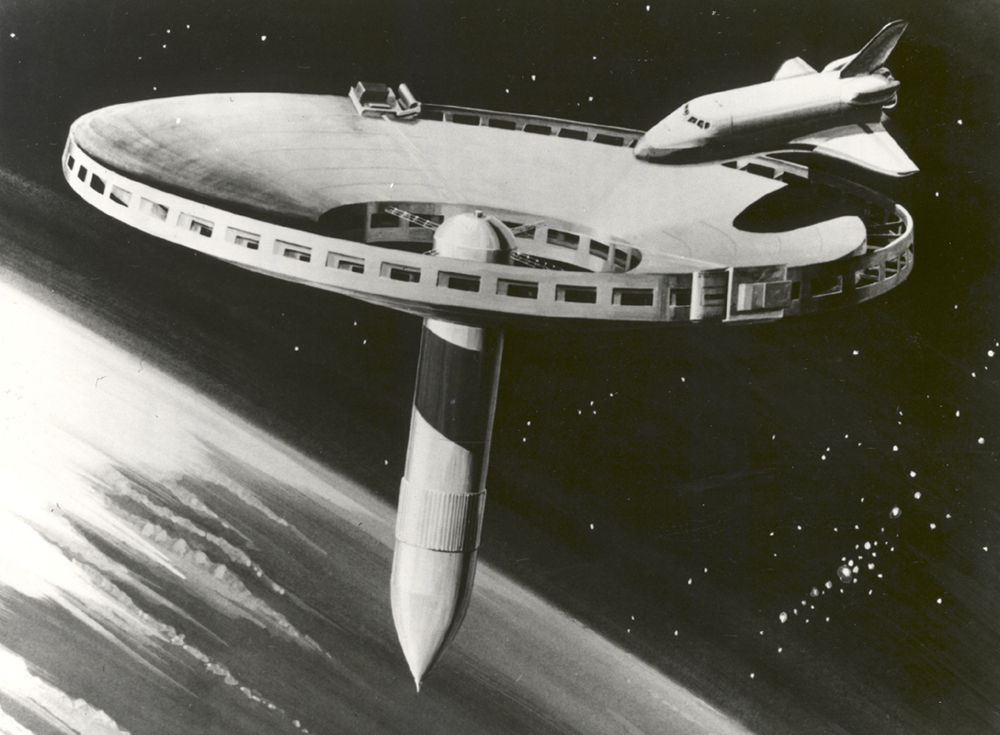

Image: An illustration from "Science Fiction Futures; Marine Corps Security Environment Forecast: Futures 2030-2045"

WATCH: The Future of Warfare: Laser Cannons and Drone Armies

Originally published on Seeker.

Eric Niiler is a science and climate reporter at The Wall Street Journal, as well as a writing lecturer at Johns Hopkins Advanced Academic Programs and a contributor to many other places such as National Geographic, the Washington Post, and more. He also has an interest in artificial intelligence and its applications in scientific and medical research. Eric has a master's degree in Science and Medical Journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor's degree in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley.