Zodiacal Light: How to See the Mysterious Glow

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Have you ever seen the zodiacal light? It is one of the most remarkable features of the solar system, yet most astronomers have never observed it. I’ve been an amateur astronomer all my life, yet I have seen the zodiacal light only once.

This light is the dim glow caused by millions of tiny particles in the plane of Earth's solar system. The solar system was born more than 4.5 billion years ago as a rotating cloud of gas and dust surrounding the new sun. This cloud coalesced into the objects now known as planets and asteroids, but some of the original dust was left behind.

This interplanetary dust mainly becomes visible when small chunks of it are swept up by the Earth, causing the streaks of light in the upper atmosphere known as meteors. But that primordial cloud is still visible on very dark, moonless nights, especially at times of the year when the ecliptic — the path of the sun through the sky — makes a steep angle with the horizon. [The Best Night-Sky Events of 2016: What to Watch for This Year]

Just as the myriad of faint stars cause the amorphous glow seen as the Milky Way, the collection of tiny dust motes that make up the interplanetary dust cloud merge to form an even fainter glow called the zodiacal light. It is called "zodiacal" because it is densest along the ecliptic or zodiac.

The zodiacal light is best seen in the evening sky in the months of February and March at the time of the waning moon, which doesn't rise until after midnight. You must be at a totally dark observing site, without the slightest trace of light pollution.

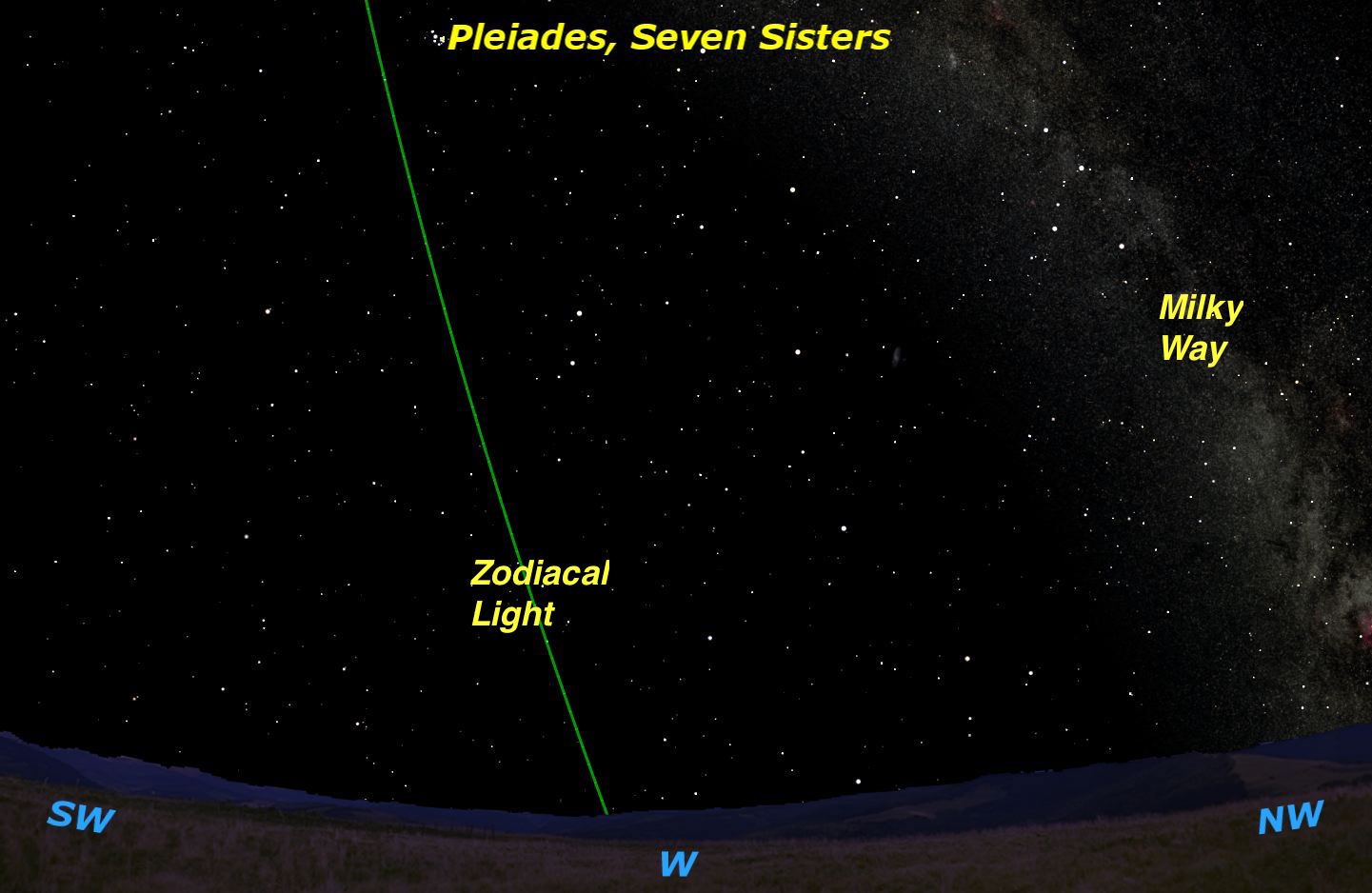

Look for the zodiacal light in the western sky about 2 hours after sunset, when all stray light from the sun is gone from the sky. The zodiacal light will appear as an extremely faint cone of light along the ecliptic, due west at this time of year, not to be confused with the Milky Way in the northwestern sky. The cone of the zodiacal light will rise toward the bright Pleiades star cluster in the constellation Taurus (the Bull).

There is an even rarer manifestation of the interplanetary dust cloud. Like the reflective letters on a road sign, these dust particles reflect light most strongly in the direction from which they are lit. So on the very darkest of nights, when the cone of the zodiacal light reaches the zenith near midnight, there is a faint brightening directly opposite the sun in the sky, known by the German word "gegenschein," meaning "counterglow."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, with the increasing light pollution everywhere in the world now, even at the darkest observing sites, the gegenschein is almost never seen today.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo of the night sky and you'd like to share it with us and our partners for a story or image gallery, send images and comments in to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com bySimulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.