Giant Dunes on Saturn's Moon Titan Sculpted by Rogue Winds

The towering dunes on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, may look similar to the sandy hills of Earth's Sahara, but their origins are completely different, researchers say. Instead of forming continuously over time like on Earth, Titans dunes are forged by short, powerful rogue winds.

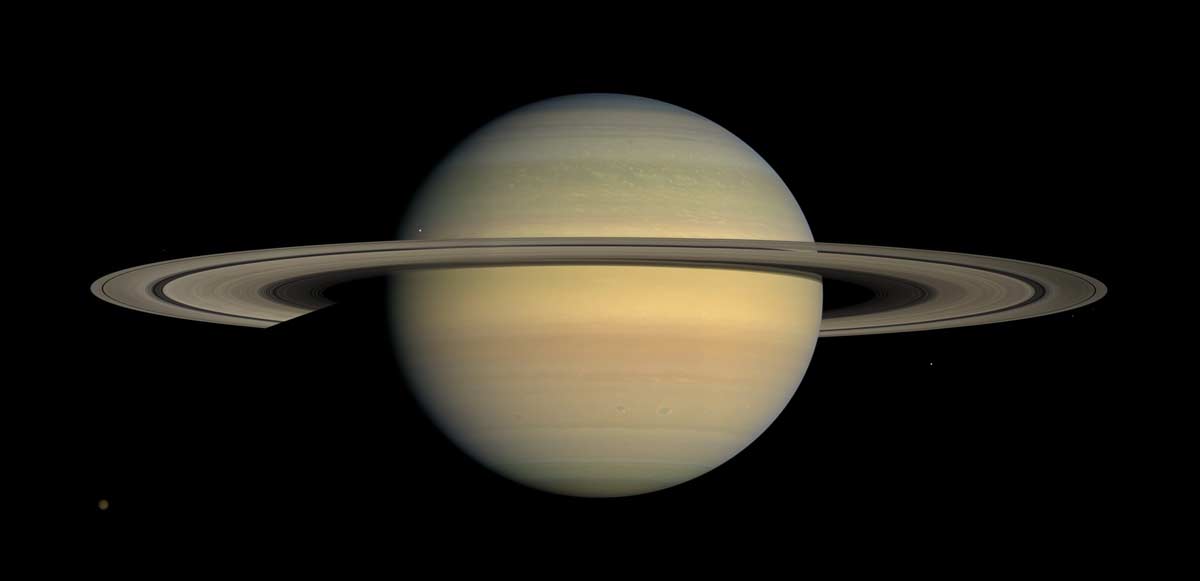

Reaching heights of more than 300 feet (91 meters), the dunes of Titan present a puzzling mystery: they seem to form in the opposite direction as Titan's steady east-to-west winds. Two new studies suggest that rare bursts of wind blowing westward are responsible for these enormous structures. The findings shed light on the remote satellite that shares many qualities with Earth.

"This work highlights the fact that the winds that blow 95 percent of the time might have no effect on what we see," Devon Burr, a planetary scientist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and lead author of one of the papers, said in a statement. [Amazing Photos of Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

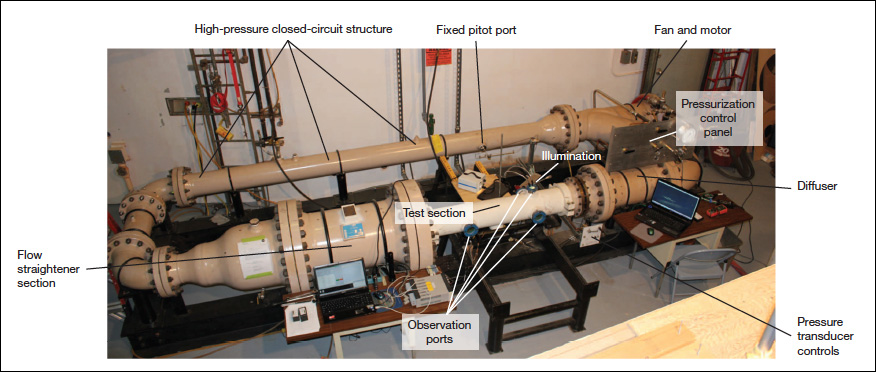

Burr, formerly with the SETI Institute, and her colleagues conducted their research in a wind tunnel built in the 1980s for studying the physics of wind-blown sand on Venus. There, they tried to recreate conditions on the surface of Titan that would influence the formation of dunes, such as a lower gravity and a thicker atmosphere than Earth's.

"It was a bear to operate, but Dr. Burr's refurbishment of the facility as a Titan simulator has tamed the beast. It is now an important addition to NASA's arsenal of planetary simulation facilities," John Marshall, of the SETI Institute, and a co-author on the new research, said in the statement.

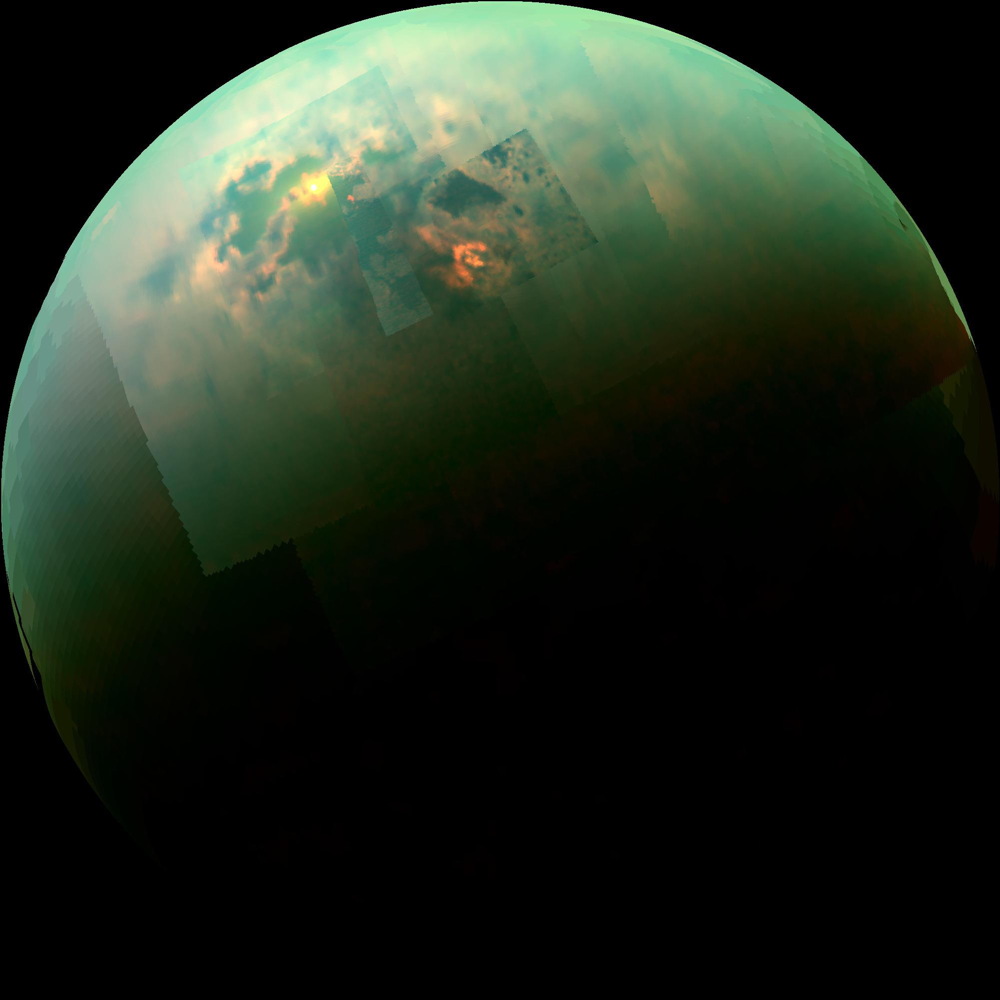

Titan's dunes are not made of the kind of sand found in deserts on Earth, but a more viscous material. Scientists don't know exactly what it is, only that it is made of hydrogen and carbon — two ingredients that can be used to create a laundry list of different materials on Earth, from methane to paraffin wax. According to Burr, the hydrogen-carbon material may coat particles of water ice.

The researchers found that the regular east-to-west winds are not strong enough to shape the viscous material into the massive dune shapes that are observed. Instead, they believe the dunes are shaped by short, rapid bursts of westerly wind. The winds on Titan "occasionally reverse direction and dramatically increase in intensity due to the changing position of the Sun in its sky," the statement said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another group of researchers investigated the formation of Titan's dunes using data from the Cassini spacecraft. Their work suggests that the dunes may have taken as long as 3,000 Saturn years to form (the equivalent of 90,000 Earth years).

According to a statement from Texas A&M, the formation of the dunes may be influenced by changes in Saturn's orbit.

"This is somewhat similar to how some of Earth's sandy deserts have evolved," Ryan Ewing, assistant professor of geology and geophysics at Texas A&M and an author on the paper, said in a statement. "In parts of the Sahara Desert, for example, some of the largest dunes are thought to have formed around 25,000 years ago and these dune patterns are still visible. Smaller dunes overprint the larger, older patterns. We see the same overprint of smaller patterns on larger ones on Titan."

The evolution of Titan's landscape is of interest to scientists partly because of the similarities between the satellite and Earth. Titan is the only moon in the solar system with an atmosphere, and the only other body besides Earth with liquid on its surface. But, Titan's lakes and oceans are made of methane and ethane, not water.

The researchers at the SETI Institute said in the statement that the study of how Titan's dunes form could have applications for understanding similar processes on Earth.

"We see today sediment being wafted over the Sahara desert, across the Atlantic to South America. This wind-blown material accounts for much of the fertility of the Amazon Basin," Marshall said. "So understanding this process is essential."

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct the following error: Titan's lake and oceans contain ethane, not ethanol.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter