How NASA's Landmark Orion Spacecraft Test Flight Will Work

NASA is planning to launch a test mission for its newest space capsule designed to eventually bring humans deeper into space than ever before. But the bold test flight, scheduled for Dec. 4, doesn't come without risks.

The space agency is sending its first Orion space capsule thousands of miles above Earth for the first time, and officials expect to retrieve it again when it splashes down in the Pacific Ocean. While the capsule will be unmanned during the test, it doesn't mean that people won't be intimately involved with some of the riskiest aspects of the mission. Officials will need to be on hand to fish Orion out of the Pacific Ocean after splashdown — a particularly risky aspect of the mission for the people involved.

"The environment in the open ocean is a hazardous environment in and of itself," Jeremy Graeber, recovery director for the test flight, said during a news conference. "Nominally, the vehicle coming down should not pose any threats to the recovery forces, but it's a test flight, so there are systems that we are not 100 percent sure we know what position they're in once we're splashed down. We have high confidence that they'll be in great shape, but we've prepared ourselves in case there are some issues." [Step-by-Step Guide for NASA's 1st Orion Spacecraft Test Flight]

Specifically, the propellant, ammonia and radiating elements of the craft used for telemetry could pose a hazard once back on Earth, but officials are prepared to handle those situations should they arise, Graeber added. The various teams working on the test flight will be in communication so that everyone remains safe.

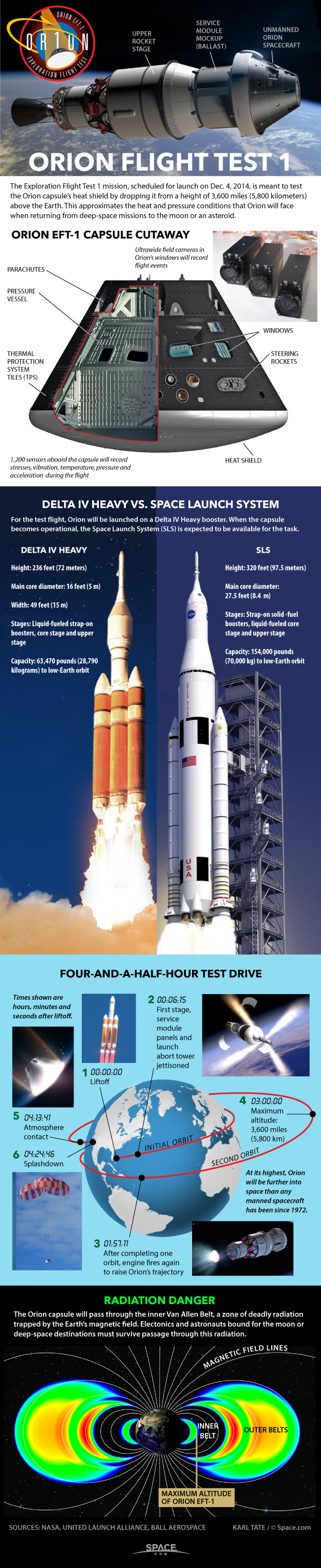

During the Dec. 4 test, called Exploration Flight Test-1, Orion — which was built for NASA by Lockheed Martin — will launch to space atop a United Launch Alliance Delta 4 Heavy rocket. The unmanned space capsule will then make two orbits of Earth, flying about 3,600 miles (5,800 kilometers) above the planet — close to 15 times higher than the orbit of the International Space Station.

When Orion hits the planet's atmosphere during re-entry, the spacecraft will be speeding at about 20,000 mph (32,000 km/h), according to NASA. The capsule's huge heat shield, the biggest of its kind ever made, will be put to the test during the re-entry. Officials will also test the spacecraft's huge parachute system used to slow down the descent of Orion after it comes through the atmosphere.

All in all, the Orion test flight should take about 4.5 hours. The test's 2-hour-and-39-minute launch window opens at 7:05 a.m. EST (1205 GMT) on Dec. 4. Splashdown should happen at about 11:29 a.m. EST (1629 GMT) if all goes according to plan.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Officials working with NASA are hoping to gather a wealth of data during the test, to see what kind of environments astronauts and the machinery protecting them might experience during a trip to space that takes them far from low-Earth orbit, where the space station is positioned.

Scientists and engineers want to test how key systems on Orion work during this test. Eventually, NASA officials hope that modified versions of Orion will take humans to deep-space destinations like an asteroid, and even Mars. Engineers working with the computers onboard Orion hope to see how the instruments behave when they're exposed to high amounts of radiation outside Earth's protective atmosphere.

"We do have radiation sensors on board, for example, so we're actually measuring different parts of the vehicle for what we're seeing, what the environment is inside," said Mark Geyer, Orion program manager. "We have 1,200 sensors, and a lot of those are loads, so they measure the impact loads when we land [and during] ascent. We'll get acoustic data inside and out, so we know how loud it is — those kinds of things. A lot of that is for the vehicle, but it's also to understand what the environment for the crew is going to be."

People on Earth will have a firsthand view of how Orion is doing throughout the test. The spacecraft will fly to space complete with cameras that should send information back to Earth throughout the test flight.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.