'The Art of Space' (US 2014): Book Excerpt

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Telling the story of space art

Ron Miller contributed this excerpt to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

In "The Art of Space: The History of Space Art, from the Earliest Visions to the Graphics of the Modern Era," artist and author Ron Miller explores the history and evolution of artwork that envisions the landscapes, life forms and technologies that could lie beyond the Earth. [The Art of Space, Envisioning the Universe (Op-Ed)]

Using more than 350 images, Miller captures centuries of space art and the science that drove it, and how that art has inspired not only imaginations, but off-world exploration. [Alien Life, Landscapes and the Art of Space (Gallery)]

Below is the first chapter from Miller's book.

Planets and Moons: Surveying our Solar System

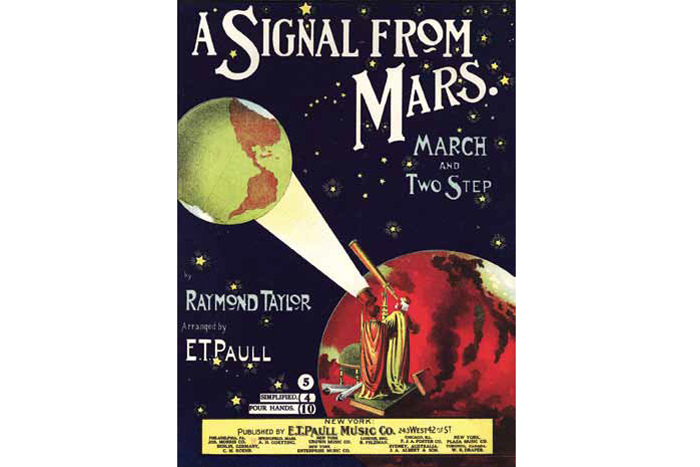

Before the publication of Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and Around the Moon (1869), literary journeys to the moon and planets were almost exclusively limited to allegory, fantasy or satire. Two things were needed to change fantasy into reality.

New worlds

It was unthinkable to the ancients that those twinkling lights might be actual places that could be traveled to, and only the moon served as a destination in a rare handful of fantasies. Even then it was not regarded as something altogether physical, but rather a kind of ethereal never-never land. But in the year 1610, and almost literally overnight, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) forever changed mankind's view of the universe. Turning a telescope to the night sky for the first time, the moon, he reported, "does not possess a smooth and polished surface, but one rough and uneven, and just like the face of the earth itself, is everywhere full of vast protuberances, deep chasms, and sinuosities." While many of the early Greek philosophers had speculated that the moon might be like this, Galileo was the first to know: he had seen it with his own eyes. Turning his telescope on the rest of the planets. Galileo discovered that they did not have the same appearance in his telescope as other stars. No matter what the magnification used, stars retained the appearance of points of light. But the planets were revealed as tiny disks with indistinct features. Jupiter, Galileo discovered, was a pale, golden globe with — astonishingly — four tiny worldlets circling it. Venus, he found, showed phases exactly like the moon. They were obviously other worlds like the moon and the earth. The Catholic Church forced Galileo to recant his discoveries and related interpretations of them, but the damage had already been done. When human beings looked skyward they no longer saw abstract points of light. They saw the infinite possibilities of new worlds.

Space travel

The German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) wrote his strange moon-voyage tale, Somnium, around the time that Galileo's discoveries first became known. It was the first science-fiction novel written by a scientist — or, for that matter, by anyone at all knowledgeable in science. And, important to us, it is perhaps the first example of an astronomical discovery influencing an art form. It is unfortunate that the novel was not illustrated, for if it had been, it might have provided the first true astronomical art.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As Galileo was discovering new worlds in the sky, so new worlds were being discovered here on earth. Scarcely more than a century earlier the continents of North and South America had been discovered quite by accident, lying unsuspected and unknown on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean. Soon, hundreds of ships and thousands of explorers, colonists, soldiers, priests, and adventurers had made the journey to these fertile, rich, and strange new lands. Now they learned that an Italian scientist had found that not only did our own earth harbor unsuspected worlds, but that the sky was full of them, too.

Little wonder, then, that Galileo's discoveries could not be easily suppressed. They were followed by an unprecedented spate of space travel stories: Somnium (published in 1634), The Man in the Moone (1638), A Voyage to the Moon (1657), A Voyage to the World of Cartesius (1694), Iter Lunare (1703), John Daniel (1752), Voltaire's "Micromegas" (1752), and countless others. If it was not possible to reach these new worlds in the sky in reality, it would be done on the page.

Visual records

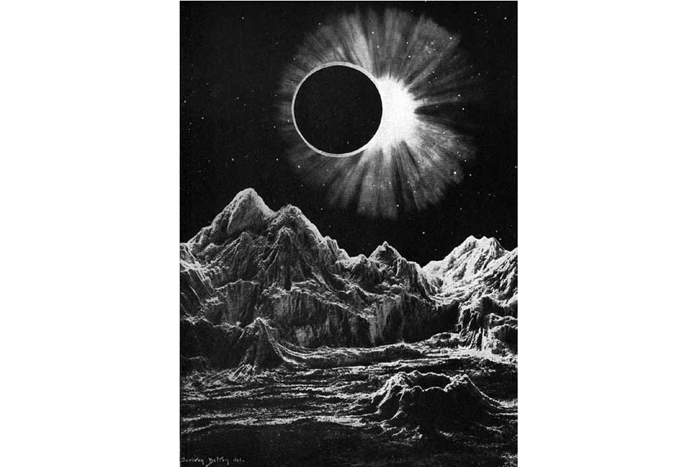

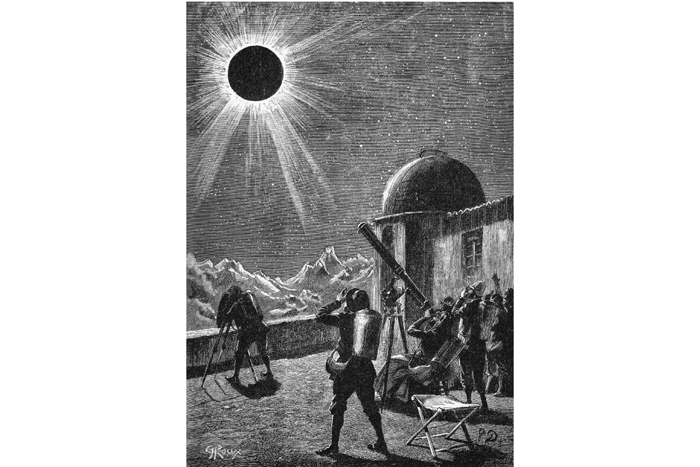

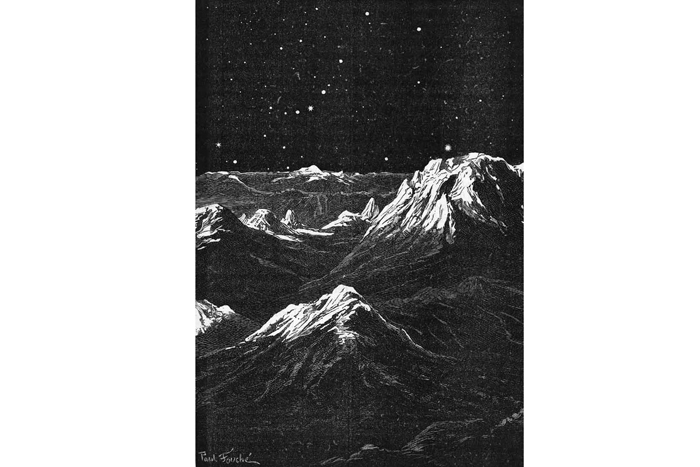

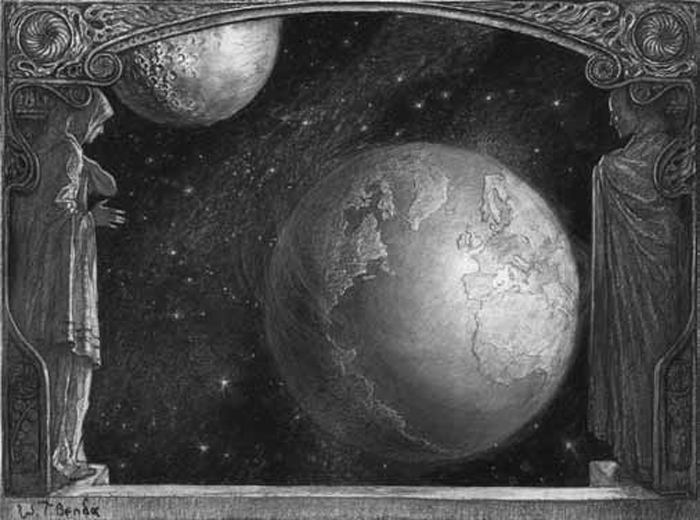

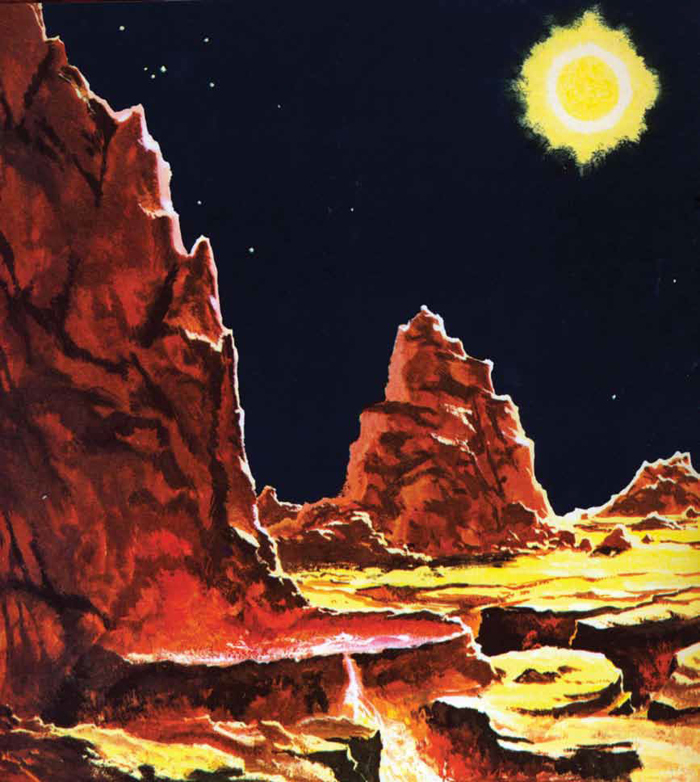

By the nineteenth century, astronomers had made vast strides in their knowledge of the moon and planets — enough so that by the 1860s, artists were finally able to create realistic views of the surfaces of those worlds. And by the beginning of the twentieth century, there was now a handful of artists who had begun to specialize in illustrating alien landscapes. Artists such as Scriven Bolton, Lucien Rudaux, and Chesley Bonestell laid the groundwork for modern space art, but their depictions of the planets were only equal to the science of the time. So in these paintings we see Mars with canals and a blue sky; Jupiter with a solid, volcanic surface; and a moon with precipitous, craggy peaks. Yet such errant leaps of imagination did not detract from the importance of these artworks. First, they played a seminal role in educating and exciting the public about earth's sister worlds. There were countless scientists, engineers, and astronomers who got their initial inspiration from paintings by these artists. Second, for the modern observer, they provide an invaluable record of the state of astronomical knowledge at the time they were created.

Chesley Bonestell: Father of Space Art

Astronautics owes much of its existence to the arts. Literary works such as Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon were directly responsible for inspiring the founders of modern spaceflight. And in the visual arts, painter, illustrator, and designer Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986) shared a vision of the universe in which space travel was truly believable.

Star of hollywood

Chesley Bonestell's life spanned almost as many careers as it did decades. Originally trained as an architect, he worked on iconic structures such as the Golden Gate Bridge and the Chrysler Building. But in 1938, aged 50, he began a new career in Hollywood. Using the skills he learned while working as an architectural renderer — techniques of perspective, light, and shade — Bonestell worked for RKO Pictures as a special-effects matte painter. One of the first films he worked on was Orson Welles's masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941), providing re-creations of turn-of-the-century New York and the moodily evocative scenes of Kane's mansion Xanadu. Over the next decade, Bonestell worked for several studios and on many movies now regarded as film classics: How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), and The Fountainhead (1949). In many instances, the entire movie screen would be filled by one of Bonestell's paintings. He eventually became the highest-paid special effects artist in Hollywood. In Bonestell's next career, he combined what he had learned as an architect and matte artist about camera angles, perspective, and painting with his lifelong interest in astronomy. In 1944 he created a series of paintings that showed the planet Saturn as seen from several of its satellites. These were immediately bought by Life magazine for its May 29, 1944, issue and published to a readership of 3 million. The paintings' realism and sense of wonder caused a sensation, especially among astronomers and science-fiction fans. Bonestell soon began collaborating with leading engineers and astronomers to illustrate the future progress of space exploration.

Visions of exploration

In 1952, Bonestell took part in the now-legendary Collier’s symposium on spaceflight — in half a dozen issues between 1952 and 1954, the magazine outlined a comprehensive and grandiose plan for the exploration of space, beginning with the launch of the first earth satellite and finishing with a manned mission to Mars. Bonestell not only provided photo-realistic illustrations of what these spacecrafts would look like, but he acted as a liaison between the scientists and his fellow illustrators, Fred Freeman and Rolf Klep. The Collier’s publications eventually proved a major contribution in "selling" both the American public and Congress on the immediate potential of spaceflight.

Enduring legacy

Since the mid-twentieth century, Bonestell's rank as "the dean of astronomical artists" remains unchallenged. His meticulous and realistic renderings of planets have been published in more than a dozen books and hundreds of magazines. Exhibitions of his paintings have been held all over the world. The first exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air & Space Museum devoted to a solo artist was dedicated to Bonestell and his work, and more than 20 original Bonestell paintings are in the permanent collection of the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. His contributions to art and science have been honored by many prestigious awards, from science fiction's Hugo to the British Interplanetary Society's Special Award and Medallion.

Astronaut Artists: Visions From Zero G

For astronomical artists and appreciators of space art, the ultimate dream is to orbit the earth or walk on the moon — to see and experience first-hand the wonders that lie beyond our planet's atmosphere. Over 500 people have traveled in space, but so far only three have been artists. The first was cosmonaut Alexei Leonov.

Russian classes

Born in 1934, Alexei Leonov graduated from a military flying school and the Zhukovsky Air Force Engineering Academy. After serving in the air force, he joined the Soviet team of cosmonauts in 1960, shortly before Yuri Gagarin's historic flight. During a glittering career he became the first human to walk in space, co-commanded the joint US-USSR Apollo Soyuz Test Flight, and was head of cosmonaut training at Star City. Always interested in drawing and painting, Leonov also studied art at the Kharkov Higher School of Pilots and eventually became a member of the Cosmic Group of the USSR Artists Union, which represented artists who were interested in astronautical and astronomical themes. He is unique among the astronaut-artists in having taken colored pencils and paper into space in order to create the first eyewitness sketches ever created of the earth in space. Leonov's work has been exhibited in the USA, Germany, France, and Russia. He is also the author of seven books, many of them illustrated with his own paintings and drawings. Another cosmonaut-artist is Vladimir Dzhanibekov. Born in 1942, Dzhanibekov became a cosmonaut in 1970, making five flights as spacecraft commander. During one of these missions he oversaw the effort that saved the Salyut 7 space station. To date, he is the most experienced of the astronaut-artists, having spent a total of 146 days in space.