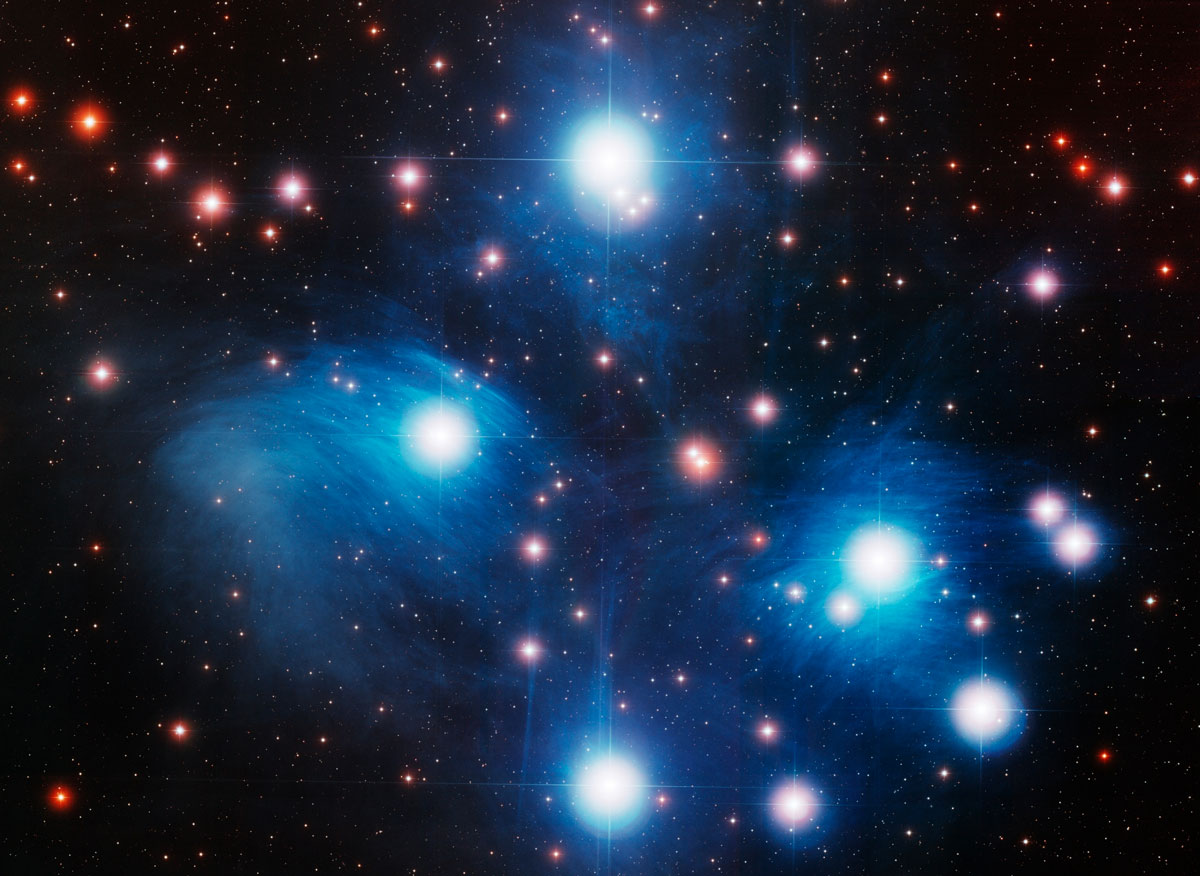

How Far, the Stars? Quasars Solve 'Seven Sisters' Star Cluster Mystery

Super-bright galaxies powered by black holes have helped astronomers come up with the most accurate distance yet to the iconic Pleiades star cluster.

The measurement, which used quasars as bright and consistent relative-distance markers, charted the famous "Seven Sisters" star cluster at 136.2 parsecs, or 444 light-years, away from Earth.

Lead researcher Carl Melis first took on the project five years ago while still in graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles, after meeting with John Stauffer (a co-author on the paper). Melis recalled being astounded to learn there was a dispute over how far away the Pleiades are from Earth. [Planets Sneak Up on Pleiades Star Cluster (Video)]

"Here's this canonical cluster — everyone knows the Pleiades, even the layperson — and we don't even know how far away it is," Melis, who is now an astrophysicist at the University of California, San Diego, told Space.com.

Visual vs. radio measurements

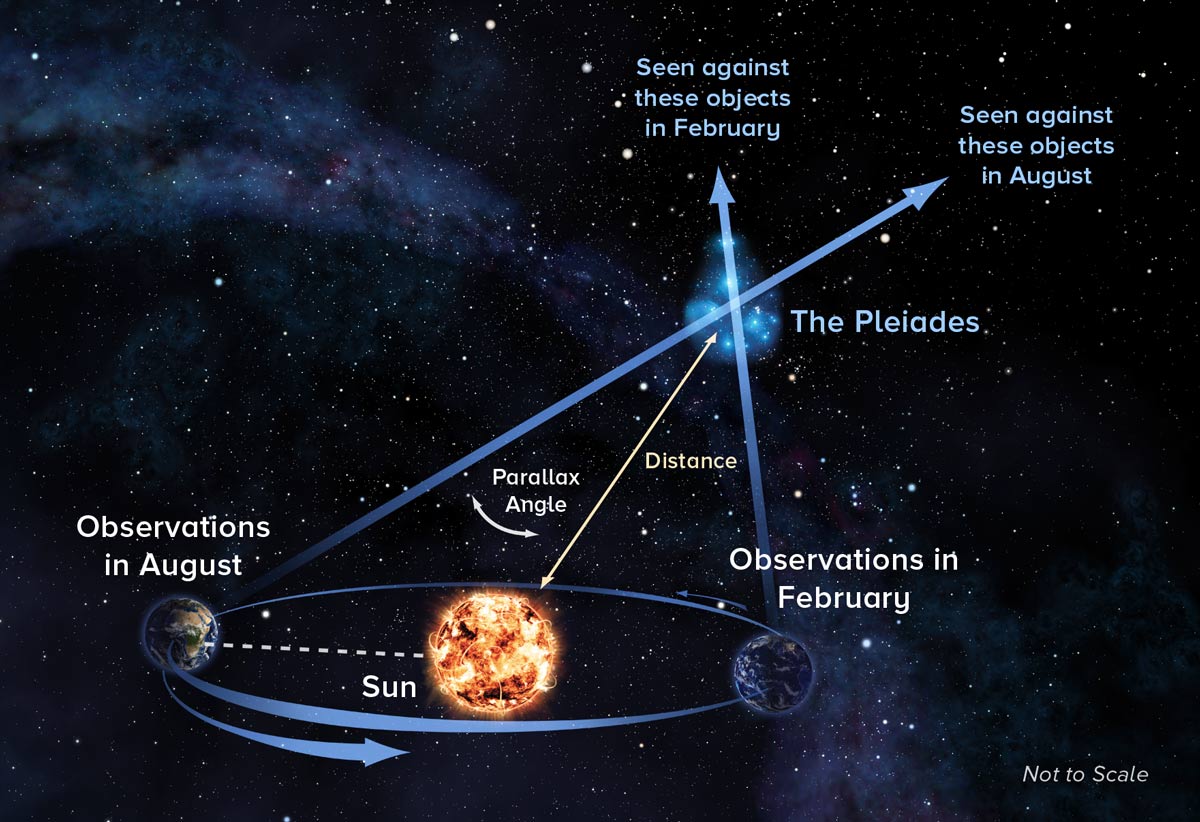

When astronomers estimate stellar distances for objects that are relatively close to Earth, they use a method called parallax. Simply speaking, measurements of a star's position relative to other stars are taken when Earth is at either side of its yearlong orbit. By measuring the change in position, astronomers can estimate the distance by simple geometry.

Scientists have known of this technique since the 1800s, but it has limitations. The biggest one is that other stars also move, which makes it difficult to come up with precise measurements.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So, instead of relying on this method, Melis' team used radio measurements to perform the work, which opened up a more reliable distance beacon: quasars, amazingly bright galactic cores powered by supermassive black holes. Quasars, which shine clearly in the spectrum of radio waves, are extremely far away — so far away that their relative motion hasn't yet been measured, Melis said.

"The beauty of this technique, as I watch my star and make measurements, is any change is entirely due to my star. The quasar just sits there. That's the difference between optical and radio techniques," Melis said.

The researchers used the Very Long Baseline Array, a network of 10 telescopes spread thousands of miles apart here on Earth, and several other radio dishes to perform the measurements. For two years, once a week, a distance measurement was taken of four Pleiades star systems, and five stars.

Along the way, researchers made a discovery: Two of those stars are a binary system, something that was suspected but had not been verified. Measurements made at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii confirmed the binary, Melis said.

Resolving a controversy?

Melis said his team's work resolves a decades-long controversy concerning just how far away the Pleiades are. Conventional parallax pegged the distance at 133.5 parsecs, or 435 light-years, while Europe's Hipparcos satellite returned a result of 120.2 parsecs (392 light-years).

Hipparcos still measured stars relative to other stars, but the sheer number of stars it used far eclipsed other measurements, Melis said. The satellite modeled the movements of about 120,000 stars, and in most cases, is considered highly accurate. Other measurements tend to use only up to 1,000 stars, he said.

"Hipparcos has been a huge success and revolutionized our understanding of stellar astrophysics, but apparently something went wrong [with this measurement], which is unfortunate," Melis said.

While he acknowledged other researchers may have their own ideas about his team's accuracy, Melis said the radio technique has been used before. Different astrophysicists have employed the method for measurements to objects such as the Orion Nebula cluster, the Taurus star-forming region and high-mass star-forming regions throughout the Milky Way.

Melis added that four more star distance measurements for the Pleiades will be incorporated into another research paper he is working on, planned for later this year. In some cases, astronomers have managed to track orbital motion of the stars, which could yield more-accurate mass measurements of the stars themselves, he added.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.