Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

An ongoing experiment could reveal whether or not our full and fleshed-out 3D universe is an illusion, a 2D projection onto a cosmic screen beyond our perception or understanding.

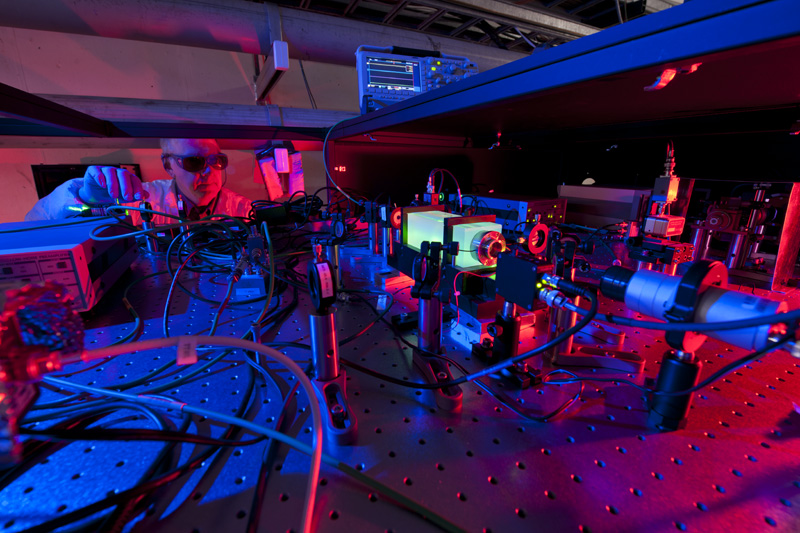

The Holometer project, which is based at the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) in Illinois, is now operating at full power, probing the very nature of space-time itself.

"We want to find out whether space-time is a quantum system just like matter is," Craig Hogan, director of Fermilab's Center for Particle Astrophysics, said in a statement. "If we see something, it will completely change ideas about space we've used for thousands of years." [See more photos of the Holometer experiment]

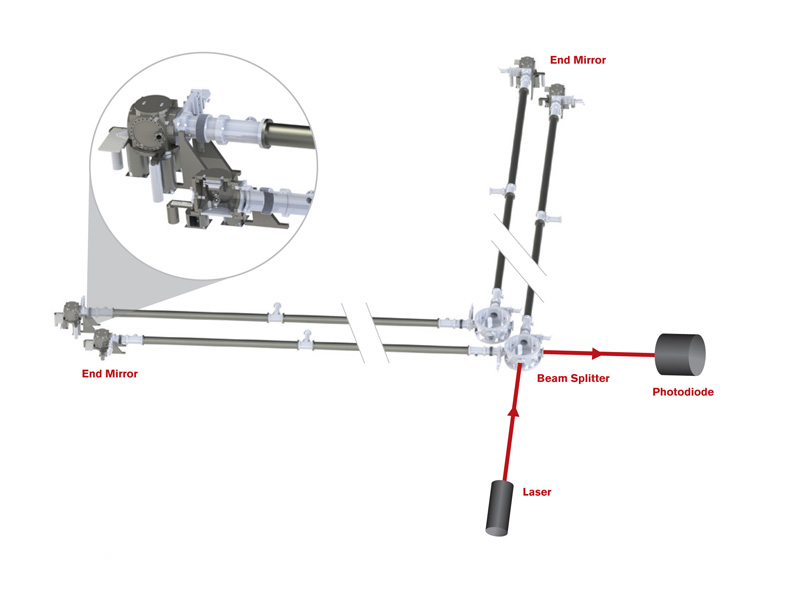

The Holometer — short for "holographic interferometer" — splits two laser beams, sending them down perpendicular 131-foot-long (40 meters) arms. A system of mirrors then bounces the light back to the beam splitter, where it recombines.

Motion causes brightness fluctuations in this recombined light. Holometer scientists are analyzing such fluctuations for anything exotic or unexpected — an effect caused by something different than ordinary ground vibration, for example.

Specifically, the team is looking for evidence of "holographic noise" — a postulated quantum uncertainty inherent to space-time that would make it jiggle, just as matter continues to move as quantum waves even when cooled to absolute zero.

These jiggles would be very slight, likely corresponding to a velocity of about 1 millimeter per year, researchers said. That's about 10 times slower than continental drift.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The experiment is basically gauging the universe's information-storage capacity, searching for signs that locations and time aren't precisely defined, researchers said. For example, all the information in the universe may actually be contained in limited two-dimensional packets, just as images on a TV screen are constructed from numerous 2D pixels.

"If we find a noise we can't get rid of, we might be detecting something fundamental about nature — a noise that is intrinsic to space-time," said Holometer lead scientist and project manager Aaron Chou, a Fermilab physicist. "It's an exciting moment for physics. A positive result will open a whole new avenue of questioning about how space works."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.