What is Pluto Made Of?

Far out in the distant reaches of the solar system, the dwarf planet Pluto lies in a neighborhood of ice and rock known as the Kuiper Belt. Frigid temperatures mean that the tiny body contains a great deal of ice. When NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew by the tiny world in July 2015, it opened up new insights into its surface and composition.

Surface of Pluto

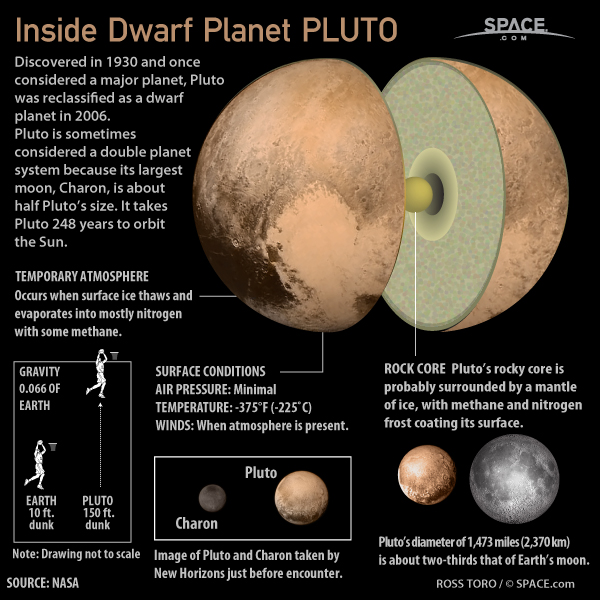

Lying 30 to 50 times as far from the sun as Earth, Pluto's composition bears a greater resemblance to the rocky terrestrial planets than the gas giants that are its neighbors. New Horizons revealed that the surface of the dwarf planet appears to be dominated by nitrogen ice, with methane and carbon mixed in.

As the spacecraft made its epic flyby, the dominant feature of Pluto was an enormous heart-shaped region informally named Tombagh Regio by mission scientists. (All of the feature names on Pluto are informal, having yet to be approved by the International Astronomical Union.) Within the heart, the features are highly varied.

"There is a pronounced difference in texture between the younger, frozen plains to the east and the dark, heavily cratered terrain to the west," Jeff Moore, leader of New Horizons' geology, geophysics and imaging team, said in a statement.

The enormous field contains icy glaciers and polygonal block-like features, as well as two mountains that may ice volcanoes. Scientists think that the blocks, located on a subsection of the heart known as Sputnik Planum, may be chunks of ice carried by the frozen nitrogen within, slowly moving over time like icebergs on an ocean. What the heart lacks is even more telling: not a single crater mars the plain, suggesting the surface is relatively new.

If the heart of Pluto is young, the rest of its skin is slightly more aged. Craters cover the surface to varying degrees, with some more heavily impacted than others. The surface also varies in color and brightness, with black, orange, and white variations. Methane varies across the surface, highly concentrated on along bright plains and crater rims, but missing from crater centers and darker regions.

Another dominant feature on Pluto is Cthulu Regio, or "the whale." Lying along the southern hemisphere, Cthulu Regio is a dark region that borders the heart. The dark colors may be composed of "tholins," complex hydrocarbons. Heavy cratering suggests the region is billions of years old, significantly older than the heart. The surface also holds onto a tenuous atmosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

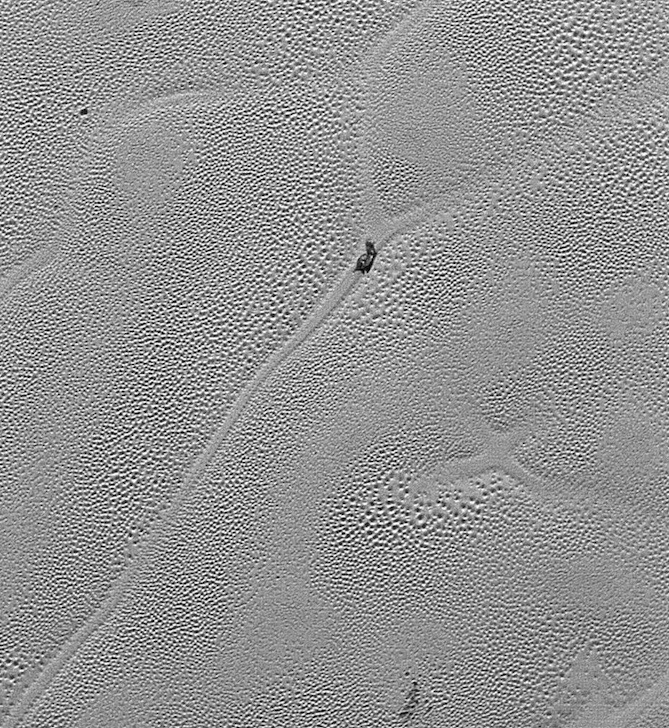

Along the line that separated day and night when the spacecraft zipped by, a region of the surface has a "snakeskin" appearance.

“It’s a unique and perplexing landscape stretching over hundreds of miles,” William McKinnon, New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging (GGI) team deputy lead from Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement.

“It looks more like tree bark or dragon scales than geology. This’ll really take time to figure out; maybe it’s some combination of internal tectonic forces and ice sublimation driven by Pluto’s faint sunlight.”

Prior to New Horizons' arrival, Pluto's distance and small size made studying it a challenge. Astronomers relied on advanced optics such as the Hubble Space Telescope to examine the dwarf planet. The powerful telescope has found new moons around Pluto in the last few years. Scientists used Pluto's largest moon, Charon, which is close to the size of the dwarf planet and similar in composition, to study the surface of Pluto. As Charon passes between Pluto and Earth, the eclipse blocks light from the surface, emphasizing the brightness changes on Pluto. They also used the moon, often called a 'twin planet' due to its similar size, to improve calculations of the size and mass of its companion.

Inside Pluto

Before New Horizons arrived, Pluto was thought to be a dead planet around a rocky core. The surprisingly youthful appearance of the tiny world suggests that the interior is far more active than anticipated. While it may contain a rocky inner core, the outer mantle layer may have once been a liquid water ocean that has only recently (in geological terms) frozen out.

The floating icebergs of Sputnik Planum provide some insight into the heating processes within the tiny world, as convective heating cells may help to explain their formation. When the ice hills that border the plain reach the convective area, they get pushed to the cells' edges, where they accumulate. One clump, informally known as Challenger Colles, is about 37 miles (60 kilometers) long and 22 miles (35 km) wide. Pluto lies in the distant Kuiper Belt, with similar rock-and-ice bodies. These pieces were left over at the beginning of the solar system. The Kuiper Belt hosts not only dwarf planets and asteroids, but also comets; scientists think that if Pluto traveled close enough to the sun, it would develop a tail. The core of a planet is the first to form, but Pluto's core failed to collect enough mass during its formation to help it escalate into a full-scale planet.

[Related: Best-Ever Pluto Photos Show Breathtaking Views of Dwarf Planet]

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTReddor Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky