Science Fiction or Fact: ET Will Look Like Us

In this weekly series, Life's Little Mysteries rates the plausibility of popular science fiction concepts.

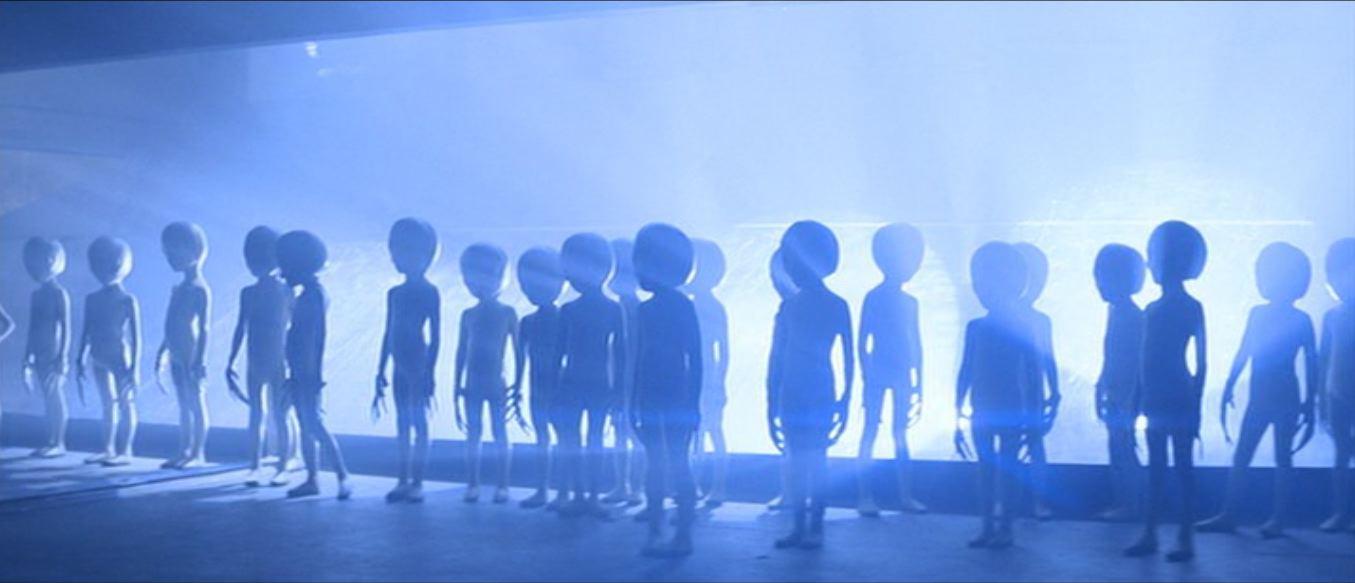

From the Klingons in "Star Trek" to the skinny, oval-eyed creatures in classic alien abduction tales, many depictions of extraterrestrials in popular culture have been decidedly humanlike. In sci-fi movies and TV, the reason is obvious: makeup is much less expensive for a humanoid alien, and it's tough to act in a giant ooze suit. Plus, it is much easier to empathize with beings that look like us, so it is no accident that evil aliens oftentimes ooze mucous and sport tentacles.

These narrative considerations aside, what is the likelihood that intelligent alien life, if we ever discover it, will actually resemble humankind?

Scientists have actually proposed solid arguments for and against E.T. developing a body plan similar to ours. At face value, if you will, it seems unlikely that organisms on another world that underwent eons of unique evolutionary history should fit comfortably into our clothes.

"Why should they look like us? No other creatures look that much like us, except for other apes," said Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute. "An alien will look like whatever its evolutionary niche is."

But maybe that's just it. Perhaps evolutionary circumstances similar to those that led us to develop limbs and fingers to manipulate tools arose on alien planets. Maybe being bipeds with bilateral symmetry is a perquisite for building socially and technologically advanced societies.

In this respect, some researchers say we possess a "pretty optimal design for an intelligent being," Shostak said. It could be that there is no other choice but for intelligent beings to look like humans. [What If Humans Were Twice as Intelligent?]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From humble origins

So far as we know, to develop complexity, life requires environmental conditions very similar to those on Earth over the last several hundred million years. And to get going in the first place, life almost certainly needs water. That is why the ongoing hunt for alien life in the cosmos has focused on finding water (or signs of it).

The current thinking is that life would probably not start out elsewhere much differently than it did here. And on the path to achieving sentience, life might very well be shaped by similar ecological pressures.

Accordingly, although separated by trillions of miles, intelligent life on Earth and Glubgar — or whatever the world's inhabitants decided to call it — could end up broadly similar. They might well consist of a torso sprouting upper and lower appendages, topped by a head studded with sensory organs.

"In the grand scheme of things, and this would include almost all aspects of life, the number of solutions available is very limited," said Simon Conway Morris, a professor of evolutionary paleobiology at the University of Cambridge.

History's arbitrariness

Nevertheless, as Conway Morris noted, the "diversity of life on Earth is enormous." That humankind looks the way it does, or that an intelligent breed of spiders did not instead evolve to build cities and smartphones, is largely due to chance, other researchers maintain.

The late Stephen Jay Gould, a famous Harvard paleontologist, doubted that if the tape of life on Earth were replayed a million times, anything like our species would evolve again. "That we have four appendages rather than six or three or five — that’s an accident of evolution," agreed Shostak. [What If the First Animals to Crawl Out of the Ocean Had Six Limbs Instead of Four?]

Indeed, if you judge success by population size, the most successful body plan on Earth involves an exoskeleton, rather than our endoskeletons, and six appendages. The possessors of that robust form: insects. "They did just fine with six," Shostak said. "There's nothing magic about four."

Although not well-regarded for their wits as individuals, the remarkable "hive minds" of bees and ants could point to another manner in which alien intelligence arises — across many individuals acting collectively, rather than as discrete beings.

Blueprints from space

Another possibility: Wise extraterrestrials might share a broadly human appearance on purpose. (Spoilers ahead!)

An episode of "Star Trek: The Next Generation" proposed that an ancient alien species, finding itself alone in the galaxy, seeded worlds with genetic programs that eventually evolved sentient beings that would look like them (with two arms, two legs and two eyes, ears and nostrils set within a head).

That end-around justification of hundreds of episodes populated by funky-faced humanoids echoes a scientific theory called panspermia. This idea holds that Earthlings did not evolve Earth. Instead, replicating biology came here in microbial form from elsewhere aboard a meteorite.

Perhaps aliens might indeed look like us, if to an extent we are them in terms of basic cellular machinery.

Humanity, past tense

Overall, it seems likely that intelligent creatures much like us are out there, somewhere. Recent estimates put the planetary census (not including moons) in the Milky Way alone at around 160 billion. "We think there are billions of planets just in our galaxy with Earthlike temperatures," Shostak said. Even if life is rare and intelligent life still rarer, statistics suggest that other humanoids exist among the billions of galaxies.

That being said, our thought experiments about alien life might come up embarrassingly short, Shostak said. Humankind developed a few hundred thousand years ago, but sentient alien races might have had billions of years more to evolve, and in that time, and could have evolved an even better body plan.

"It may be beyond our ability to say very much meaningful about all these things," Shostak said. "It's sort of like asking trilobites, 'What do you think will run the planet in 500 million years?'"

Or, they could have ditched fleshy bodies all together. Shostak and other researchers suspect that artificial intelligence will soon supersede and possibly replace fragile biological beings. Sentient, practically immortal robots, then, might be the shape of things to come.

Plausibility Score: Given the estimated bonanza of habitable worlds with Earth-like evolutionary pressures, aliens that look remarkably like us are quite likely to be out there, and even in our galaxy, so we give humanoid aliens three out of a possible four Rocketboys.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com.

Adam Hadhazy is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He often writes about physics, psychology, animal behavior and story topics in general that explore the blurring line between today's science fiction and tomorrow's science fact. Adam has a Master of Arts degree from the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Boston College. When not squeezing in reruns of Star Trek, Adam likes hurling a Frisbee or dining on spicy food. You can check out more of his work at www.adamhadhazy.com.