NASA Telescope Discovers 26 Alien Planets Around 11 Different Stars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

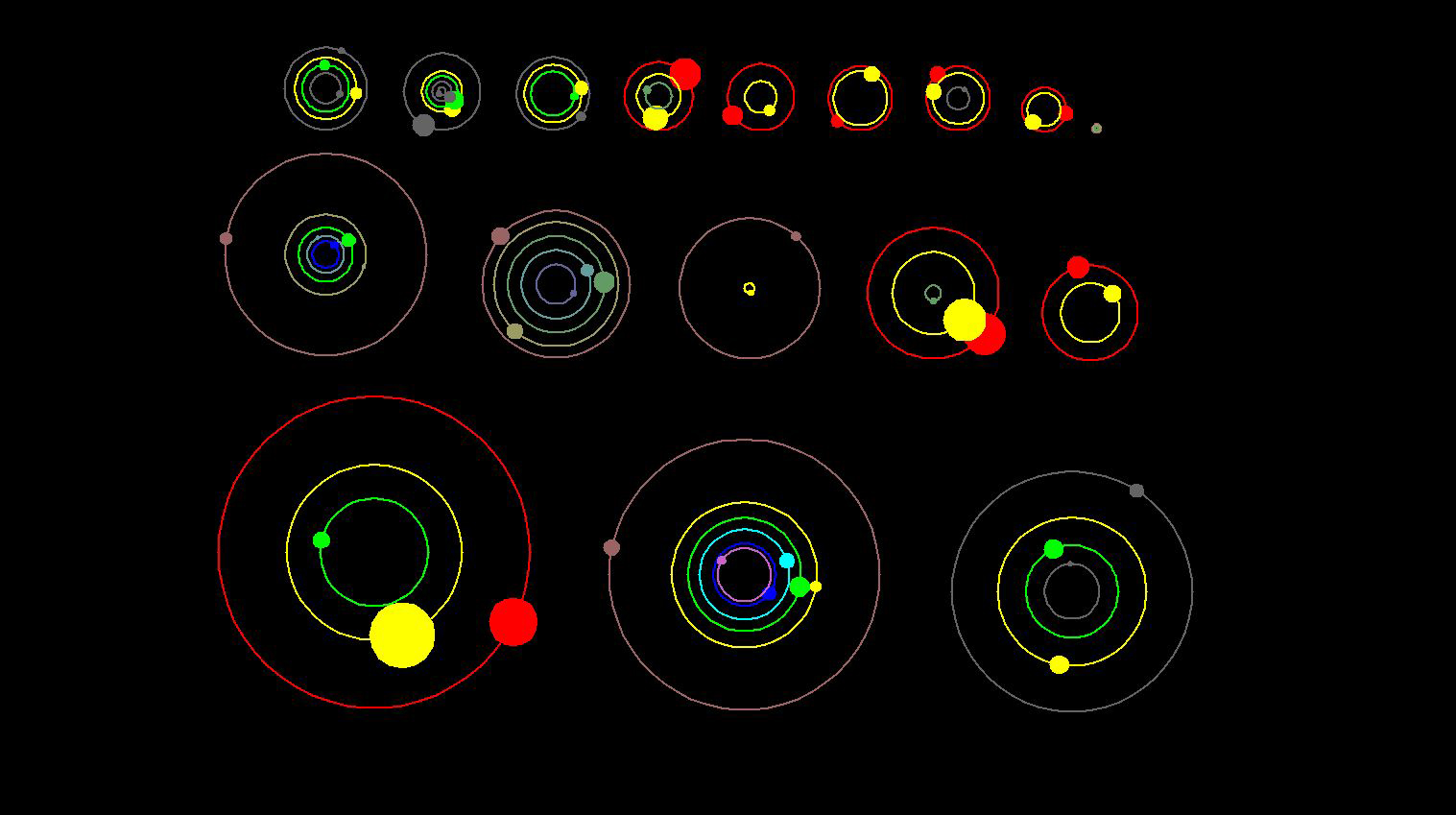

NASA's prolific planet-hunting spacecraft has hit the jackpot again, discovering 11 new planetary systems with 26 confirmed alien planets among them.

The findings nearly double the number of bona fide planets found outside our solar system by the Kepler space observatory.

"Prior to the Kepler mission, we knew of perhaps 500 exoplanets across the whole sky," Doug Hudgins, Kepler program scientist at NASA headquarters in Washington, said in a statement. "Now, in just two years staring at a patch of sky not much bigger than your fist, Kepler has discovered more than 60 planets and more than 2,300 planet candidates. This tells us that our galaxy is positively loaded with planets of all sizes and orbits."

Article continues belowThe newly detected worlds vary in size from 1.5 times the radius of Earth to larger than Jupiter; 15 of the 26 planets fall between Earth and Neptune in size. While all of the planets tightly orbit their parent stars, more research will be required to determine which worlds are rocky like Earth, and which have thick, gaseous atmospheres like Neptune, the scientists said.

Still, all of the 26 new planets orbit closer to their stars than Venus does to our sun. This means that their orbital periods — or the time it takes for them to complete one orbital lap around the star — range from six days to 143 days, according to the researchers. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets ]

By studying these different planetary systems, scientists can glean valuable information about how planets form.

Hunting for planets

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Kepler spacecraft, which orbits the sun, stares at a patch of sky that contains 150,000 stars and locates potential alien planets by measuring the tiny change in brightness that occurs when a planet transits — that is, passes in front of — a star.

Once a planetary candidate is identified, further observations are conducted by ground-based observatories to weed out the false positives.

"Confirming that the small decrease in the star's brightness is due to a planet requires additional observations and time-consuming analysis," Eric Ford, associate professor of astronomy at the University of Florida, explained in a statement.

Ford is the lead author of a study that confirms two of the new systems, Kepler-23 and Kepler-24.

"We verified these planets using new techniques that dramatically accelerated their discovery," Ford said.

Each of the newly found planetary systems holds two to five closely spaced transiting planets, the researchers said. Since these systems are tightly packed, the planets exert gravitational forces on one another, speeding up or slowing down their orbits. The orbital period of each planet is altered in the process.

By measuring the orbital changes, Kepler can identify potential planets in the system. This method, known as Transit Timing Variation, can be used to verify alien planets without extensive ground-based observations. The technique also increases Kepler's ability to confirm planetary systems around fainter and more distant stars, the researchers said. [Video: Kepler Reveals Lots of Planets: Some Habitable?]

"By precisely timing when each planet transits its star, Kepler detected the gravitational tug of the planets on each other, clinching the case for 10 of the newly announced planetary systems," Dan Fabrycky, of the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement.

Fabrycky is the lead author of the paper that confirms the Kepler-29, -30, -31 and -32 systems.

Alien planets and their host stars

Five of the systems (Kepler-25, -27, -30, -31 and -33) contain a pair of planets, the inner one circling its star twice in the time it takes the outer planet to make one lap.

Four of the systems (Kepler-23, -24, -28 and -32) are home to a pair of planets where the outer one orbits the star twice for every three times the inner planet circles the parent star.

"These configurations help to amplify the gravitational interactions between the planets, similar to how my sons kick their legs on a swing at the right time to go higher," Jason Steffen, a postdoctoral fellow at Fermilab Center for Particle Astrophysics in Batavia, Ill., said in a statement. Steffen is the lead author of a paper confirming the Kepler-25, -26, -27 and -28 systems.

The system with the most planets is Kepler-33. The star, which is older and more massive than the sun, hosts five planets that range in size from 1.5 to five times that of Earth. All of these planets orbit closer to their star than any planet circles our sun.

Once the properties of a star are understood, such as the telltale light signature of a planet crossing in front, it becomes easier to eliminate false positives, the researchers said.

"The approach used to verify the Kepler-33 planets shows the overall reliability is quite high," said Jack Lissauer, planetary scientist at NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., and lead author of the paper on Kepler-33. "This is a validation by multiplicity."

The newly discovered planets increase the Kepler mission's tally of confirmed planets to 61, with 2,326 other planetary candidates.

The four separate papers appear in the Astrophysical Journal and the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.