Jupiter's Moons to Perform Weekend Show for Skywatchers

This weekend, a remarkable series of events will take place on Jupiter: The planet's four big moons will cast shadows on the gas giant planet that can be seen from Earth using a small telescope.

The planetary shadow play, which begins Saturday night (Nov. 6) and runs through early Sunday, will be primarily visible from the western coast of the United States. [Illustration: Moon shadows on Jupiter]

The four bright moons of Jupiter are known as the Galilean moons after their discoverer Galileo Galilei. As they revolve around Jupiter, they sometimes pass across the face of the planet as seen from Earth, as well as behind the planet and in its shadow.

All of these events can be observed with a small telescope. You just need to know where — and when — to look.

How to see Jupiter's moon shadows

First, a word of caution: The overnight between Saturday and Sunday is when we switch back from daylight saving time to standard time, so be careful you get the correct time for your location.

Because the complete sequence of events is only observable from the U.S. West Coast, we will use Pacific Time here to discuss the best viewing times. Observers further east will miss the later events, and should add the appropriate number of hours to the times depending on their location and time zone.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The show begins at 8:53 p.m. PDT (11:53 p.m. EDT) on Saturday (Nov. 6), when Jupiter’s largest moon Ganymede begins to cross the planet's face.

Because Ganymede has a relatively dark surface, it appears bright against the limb of Jupiter — but quickly appears to change to a dark gray against the bright central parts of Jupiter's disk. This can be seen with telescopes that have as small as a 5-inch aperture.

At 9:47 p.m. PDT, a second moon — Europa — follows Ganymede across Jupiter's face.

Because Europa’s surface is icy, it reflects a much more light than Ganymede, and closely matches Jupiter's cloud belts behind it. As a result, it vanishes in all but the largest telescopes, perfectly camouflaged.

At 10:24 p.m. PDT, yet another moon — the volcanic Io — begins to disappear behind the opposite side of Jupiter.

At 11:52 p.m. PDT, Europa's shadow starts to take a notch out of the western limb of Jupiter. This can be seen with telescopes that have as small as a 3-inch aperture. Two minutes later, Ganymede moves off the disk of Jupiter and is once again a bright spot in the sky.

The Great Red Spot gets black eye

By now, Jupiter's Great Red Spot has begun to rotate into view, right behind the shadow of Europa. The Great Red Spot now has a black eye.

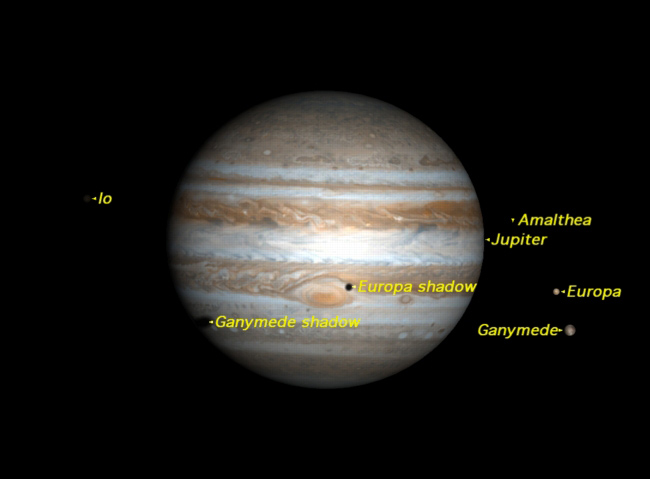

This computer-generated image shows a simulation of how Jupiter will appear in telescopes at 12:15 a.m. PDT on Sunday, Nov. 7.

Note that this uses a generic image for the planet’s cloud surface — currently, the cloud belt in which the Great Red Spot rides has faded to match the neighboring bright zones. Io has emerged from behind Jupiter itself, but is still eclipsed by Jupiter’s mighty shadow and hence invisible.

But wait, there's more — the Jupiter moon show isn't over just yet. Here's a rundown of the movements of Jupiter's moons to watch for on Sunday:

- At 12:31 a.m. PDT, Europa leaves the disk of Jupiter.

- At 1:12 a.m. PDT, a second shadow, that of Europa, puts the bite on the west limb of Jupiter. We now have two shadows creeping across the face of Jupiter, while the moons casting them are off to the right, a wonderfully three-dimensional effect.

- At 1:41 a.m. PDT, Io emerges from Jupiter's shadow, ending its eclipse.

- At 2:00 a.m. PDT, Daylight saving time officially comes to an end, and you should move your clock back to 1 a.m.

- Now, at 1:34 a.m., Pacific Standard Time, Europa’s shadow moves off Jupiter's disk. Finally, at 3:08 a.m. PST, Ganymede’s shadow also moves off the disk.

You may be puzzled by the fact that Ganymede leads Europa across Jupiter’s disk, but Europa’s shadow precedes Ganymede’s all the way across.

That’s because Europa orbits much closer to Jupiter than Ganymede, so that the angular distance between Ganymede and its shadow is much greater than the angular distance between Europa and its shadow.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.