Super-Old Supernovas Spotted Across the Universe

Astronomers have peeled back layers of time to reveal a dozen of the most ancient star explosions ever seen, researchers announced today (Oct. 5).

These explosions, called supernovas, helped seed the universe with chemical elements, and scientists are able to use them as mile markers to measure the cosmos.

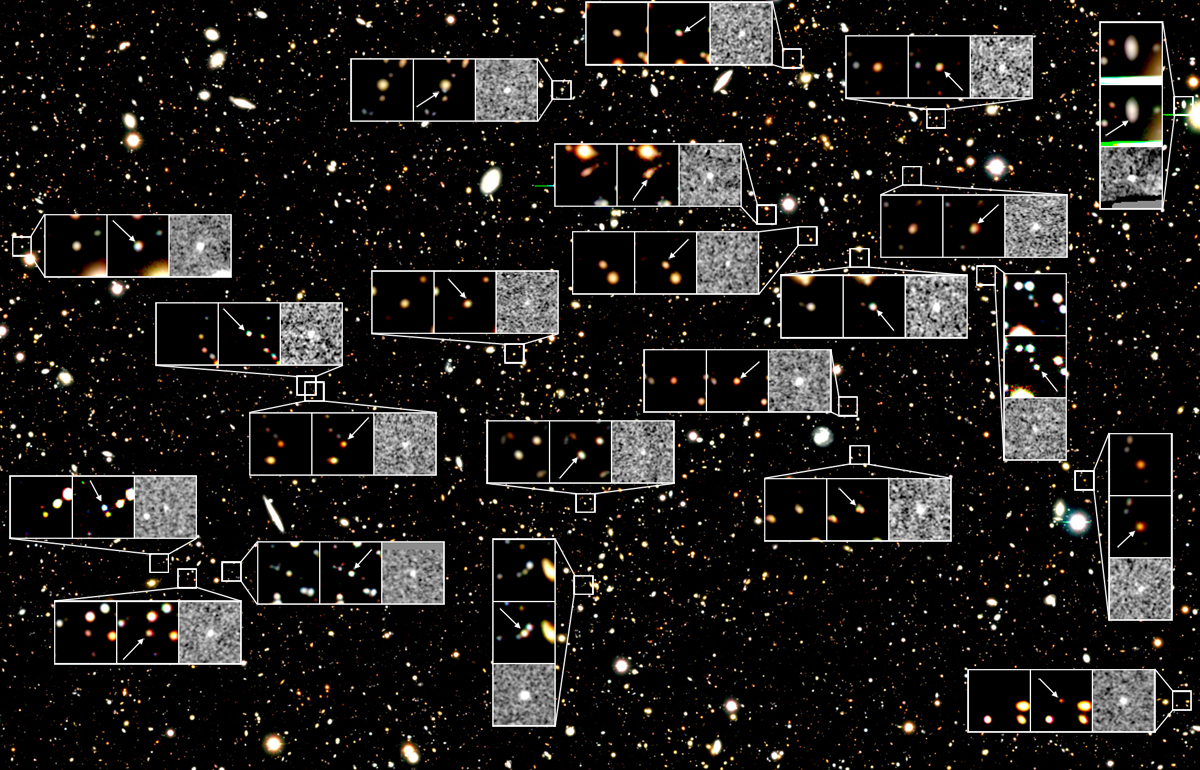

Researchers from Tel Aviv University pointed the huge Japanese Subaru Telescope in Hawaii at a patch of the sky as big as the full moon and let their cameras collect the accumulated light from several nights of observations. This allowed the scientists to image very faint objects from extremely far away, whose light has taken billions of years to reach Earth. Thus we are getting a picture of them as they were eons ago, when the light was first emitted. [Photos of Great Supernova Explosions]

In all, the scientists observed 150 supernovas in this bit of sky, 12 of which occurred around 10 billion years ago, meaning they exploded when the universe was only 3.7 billion years old, about one-third its present age of 13.7 billion years.

Violent cosmic deaths

Some supernovas are the violent deaths of massive stars. When these stars have burned up all their fuel, they finally succumb to the inward pull of gravity and collapse to become dense remnants such as neutron stars and black holes. In the process, they expel copious amounts of energy in a short and powerful explosion that's so bright we can see it across the universe.

Other supernovas occur when a special type of smaller star, called a white dwarf, slowly siphons off mass from a companion star, until it becomes too heavy and collapses in a similarly luminous detonation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This kind of supernova, called Type 1a, always occurs when the star has reached a particular mass threshold, called the Chandrasekhar limit, and therefore Type 1a supernovas always release the same amount of radiation. By comparing their apparent brightness on the sky with the brightness they would have if an observer were right next to them, astronomers can measure their distances.

For this reason, Type 1a supernovas have become handy cosmic yardsticks that have helped astronomers realize that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, apparently due to a mysterious force called dark energy — a discovery that was awarded the 2011 Nobel Prize in physics.

The new research revealed that Type 1a supernovas were about five times more common during this ancient epoch, 10 billion years ago, than they are today.

Element factories

Supernovas are factories for heavy elements in the universe. Just after the Big Bang that started the cosmos, the universe was mostly made of hydrogen and helium, the two lightest elements. (They have one and two protons each, respectively.)

As stars formed and carried out nuclear fusion in their cores, elements like carbon, nitrogen and oxygen were created. But to make anything heaver than iron, which has 26 protons per atom, would take a supernova. Only the extreme energies of these explosions are powerful enough to fuse these elements.

Supernovas not only create these heavy elements but disperse them throughout space when they explode. Then the elements are caught up and made into new generations of stars, and eventually find their way into planets like Earth.

"These elements are the atoms that form the ground we stand on, our bodies, and the iron in the blood that flows through our veins," astronomer Dan Maoz, one of the leaders of the new study, said in a statement.

And without supernovas, none of this would be possible. By studying these ancient explosions, the scientists hope to learn more about the timeline of element creation in the universe.

The research was led by Tel Aviv University astrophysicists Maoz, Dovi Poznanski and Or Graur, and included scientists from the University of Tokyo, Kyoto University, the University of California Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The findings are reported this month in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.