Jupiter's Moon Shadows Move Like Clockwork

Did you know that there is a gigantic and extremely accurate clock with four "hands" in our solar system? And that you can watch this clock on nearly any clear night?

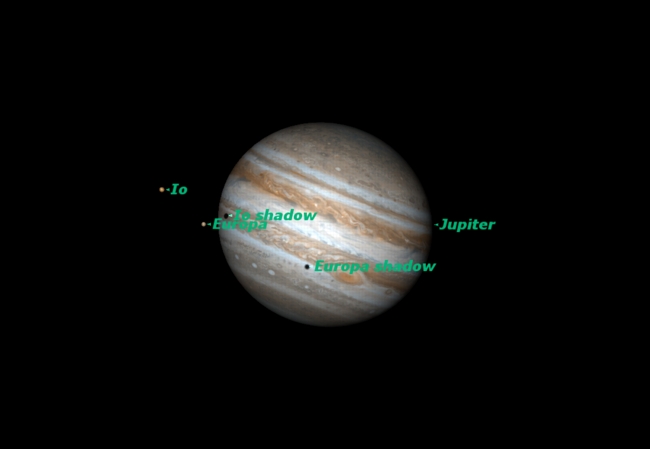

The cosmic timepiece is created by Jupiter's four largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, which behave like hands on a clock with the gas giant planet at the center. As the moons cross Jupiter's face, they create shadows visible in telescopes, and skywatchers have a chance to spot this moon shadow play on May 25.

The Jupiter clock was discovered by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilee in 1609 when he first turned his newly constructed telescope toward the planet. [Photos: Jupiter, Solar System's Largest Planet]

The Jupiter clock

Like the hands of any good clock, the four Galilean moons of Jupiter travel around the planet with extreme accuracy.

When the Jovian moons are off to the side of Jupiter, they are easy to see in the smallest of amateur telescopes as tiny bright points of light. When they pass directly in front of Jupiter, they almost vanish against the bright background of the planet.

When the sun, as seen from Earth, is off to the side, the moons cast their shadows on the face of Jupiter, causing eclipses. Although these shadows are very small, they are also very dark and can be seen in medium-size telescopes with at least a 90mm aperture.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Because the volcanic moon Io whizzes around Jupiter once every 1.8 Earth days, its shadow is the one most commonly seen. Europa takes 3.5 days to complete the circuit, so its shadow is seen less often.

Ganymede's shadow is rarer still, and at present, Callisto's shadow misses Jupiter entirely.

Because Europa's period is almost exactly twice that of Io, they often line up to cause "double features." [Video: Touring Jupiter's Biggest Moons]

The Jupiter window

With Jupiter's satellites spinning around the planet so quickly, you'd think we’d often see these shadows. However, each shadow takes only an hour or so to cross Jupiter, and the planet itself is visible for only a brief period every day.

This is especially true this early in the apparition, when we catch only brief glimpses of Jupiter between when it rises high enough to clear the turbulence in Earth's atmosphere and when the sun floods our sky with light.

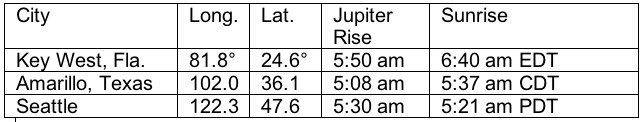

In late May this "window" opens briefly around 5:30 a.m. local time. The exact times vary from location to location; any planetarium program will let you narrow it down. Here are some examples from different locations in the United States:

As you can see, the farther north you are, the "narrower" your window is. In Florida, it's 50 minutes long. In Amarillo, nearly half an hour, and in Seattle, none at all. The sun rises over Seattle nine minutes before Jupiter would be high enough to observe.

Fortunately, a double transit takes quite a while to unfold, so even if you have a limited window, you may still see part of the show.

Jupiter phenomena

As mentioned earlier, this "clock" is very accurate, so the “phenomena” of Jupiter’s satellites can be calculated far in advance, and tables are available in the RASC Observer’s Handbook and on the Internet.

The first of the current series of double transits is not visible from North America, but the second in the series will be, on Wednesday, May 25. What you have happening is two satellites, Io and Europa, passing in front of Jupiter, casting their shadows ahead of them.

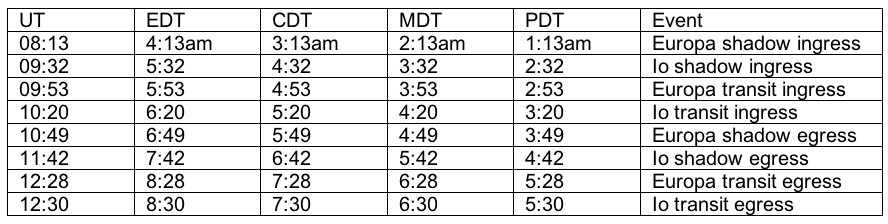

The timings of the series of events are as follows (times are usually given in Universal Time, but are converted to major time zones below):

If this seems confusing to you, think of two dancers, Io and Europa, entering from the left side of a stage, with a light to their left casting their shadows on the stage backdrop. The shadows enter first, then the performers. At the end of the scene, the shadows leave first, followed by the performers.

If you match up the times of the events with the observing windows above, you’ll see that an observer in any part of the country sees only part of the show.

Observers on the eastern seaboard will see only the beginning; those on the West Coast will see only the end. Those in the middle will see most of the show.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.