Icy Saturn Moon Pumps Out 15.8 Gigawatts of Heat Power

The south polar region of a frigid Saturn moon churns out far more heat than Yellowstone National Park, Earth's most famous geologic hotspot, a new study finds.

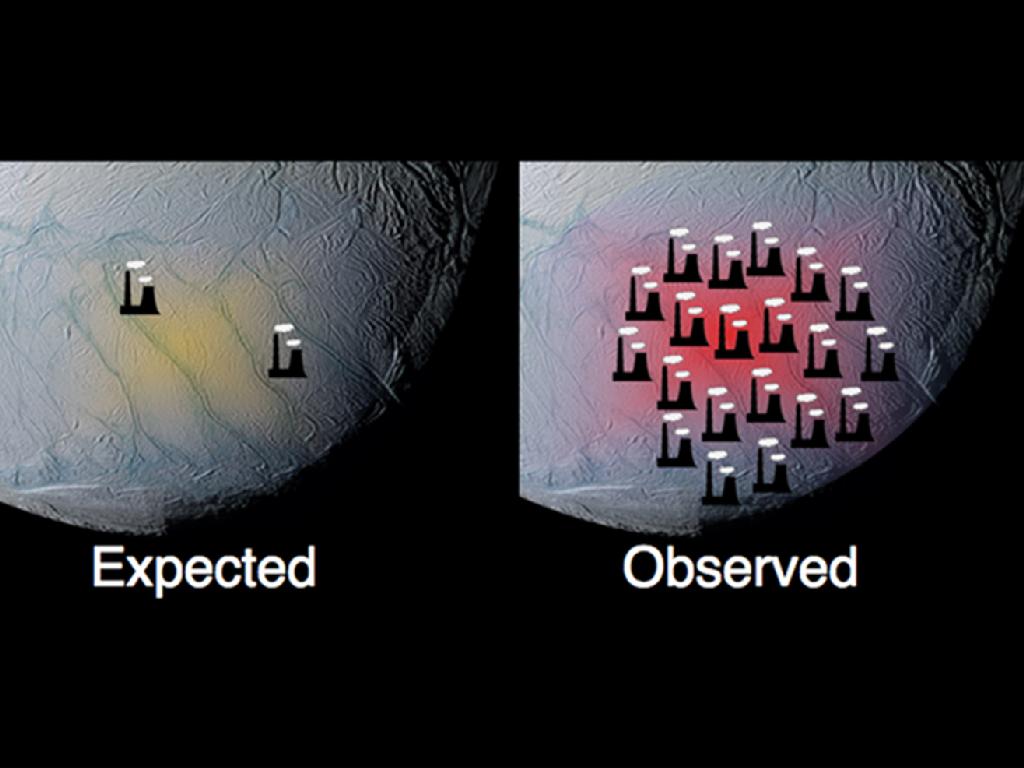

Using data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft, researchers have determined that the far southern reaches of the Saturn moon Enceladus produce about 15.8 gigawatts of heat-generated power. That's about 2.6 times the power output of all the hot springs in and around Yellowstone — and 10 times more than scientists had predicted, researchers said.

The new find is intriguing to scientists since it adds more evidence for the likelihood of a liquid-water ocean under Enceladus' icy shell. But it's puzzling as well — researchers aren't sure where all that heat is coming from. [Gallery: The Rings and Moons of Saturn]

"The mechanism capable of producing the much higher observed internal power remains a mystery and challenges the currently proposed models of long-term heat production," study lead author Carly Howett, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., said in a NASA statement Monday (March 7).

A hotspot on an icy world

Enceladus is Saturn's sixth-largest moon and has a frigid surface but an active, roiling interior — at least near its south pole. In that region, geothermal activity is centered on four roughly parallel trenches informally known as "tiger stripes."

These fissures — each about 80 miles long and 1.2 miles wide (130 by 2 kilometers) — eject great plumes of water vapor and other particles into space. Cassini first discovered the Enceladus ice geysers in 2005.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the new study, researchers used Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer to study the surface temperatures in Enceladus' south polar region. They then used the observations to determine the area's heat output.

The 15.8 gigawatts of heat on Enceladus measured by Cassini is roughly equivalent to the output of 20 coal-fired power plants. This came as a surprise, since a previous study had predicted that the region should generate only about 1.1 gigawatts, with Enceladus' own natural radioactivity adding another 0.3 gigawatts to that mix, researchers said.

The team reported its findings in the March 4 issue of the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Fueling Enceladus' heat engine

Much of Enceladus' internal heat likely comes from tidal forces generated by the moon's interactions with Dione, another Saturn satellite.

It is possible that Enceladus' orbital relationship to Saturn and Dione changes over time, spurring some periods of intense tidal heating and some periods of relative quiescence, researchers said.

So Cassini may just be catching Enceladus during an abnormally hot spell — which could explain the surprisingly high heat flows.

The new results make Enceladus an even more attractive candidate to support life as we know it. Scientists had suspected that a huge, liquid-water ocean sloshes beneath the moon's icy crust, and the increased heat readings only make this supposition more likely, researchers said.

On Earth, life almost invariably gains a foothold wherever liquid water exists, so "follow the water" has become a mantra for scientists searching for life beyond Earth.

"The possibility of liquid water, a tidal energy source and the observation of organic [carbon-rich] chemicals in the plume of Enceladus make the satellite a site of strong astrobiological interest," Howett said.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.