The Mars Rovers

Reference Article

Rovers are one of the major workhorses of modern-day Mars exploration. Over the last two decades, these six-wheeled robotic emissaries have grown steadily in size and capability, providing important ground-truth information about the Red Planet's geological present and its ancient past. With their ability to move around and investigate multiple locations, rovers have given researchers access to much wider swaths of Mars than prior immobile landers and have provided compelling evidence that the planet was once much more habitable than it is today.

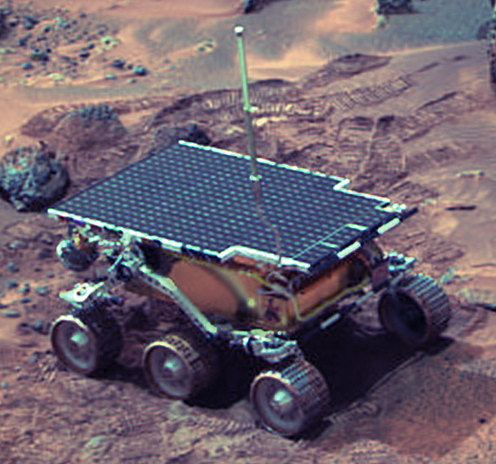

Sojourner

The first Mars rover was Sojourner, named for abolitionist and early women's rights activist Sojourner Truth. It arrived on Mars on July 4, 1997, with NASA's Pathfinder mission, the first probe to touch down on the Martian surface since the Viking landers of 1976. Pathfinder landed in an area called Ares Vallis, a large, ancient flood plain that was chosen so that Sojourner would be able to easily rove around and analyze rocks.

Compared to later explorers, Sojourner was tiny. NASA described it as a "microrover" and gives its dimensions as 26 inches (66 centimeters) long, 19 inches (48 cm) wide and 12 inches (30 cm) tall — roughly the size of a filing cabinet drawer. It roved on six 5-inch (13 cm) wheels that could each move independently, so that if one got stuck in Mars' soft sands, the others could work to power the robot forward. Sojourner's top speed, according to NASA, was 0.015 miles per hour (0.024 kilometers per hour).

The rover contained front and rear cameras as well as hardware to conduct scientific experiments. A solar panel on its top provided power. Sojourner analyzed rocks near its landing site, which were given nicknames such as Barnacle Bill, Scooby-Doo and Yogi. The investigations suggested that Ares Vallis had been extremely water-rich in the past and had formed from floods that originated near the landing site. Sojourner was designed to operate for just one week but ended up living for three months, traveling nearly 330 feet (100 meters) from Pathfinder and sending back more than 550 images.

NASA last heard from Pathfinder on Sol 83 of the mission, which in Earth time was Sept. 27, 1997. The agency believes that the probe stopped working because its battery got overloaded from repeating charging and de-charging.

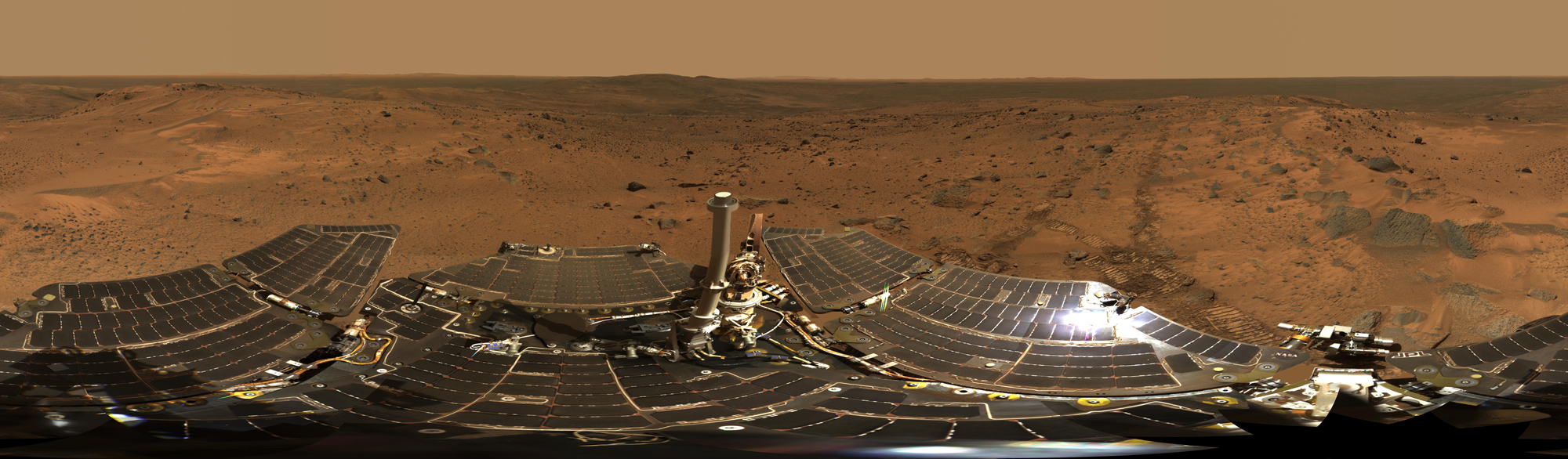

Spirit and Opportunity

The next Mars rovers were the golf-cart-size twins, Spirit and Opportunity. They landed a few weeks apart in January 2004 and soon began searching for signs of past water activity on the Red Planet. The solar-powered rovers towered over their predecessor Sojourner, standing 4.9 feet (1.m) high and weighing 400 lbs. (180 kilograms).

Spirit touched down at a location called Gusev Crater, which was suspected of being a lake at some point in the past. The rover found ample evidence of rocks that had formed through interaction with water. In 2005, Spirit scaled a mountain the height of the Statue of Liberty, and for the first time recorded Martian dust devils as they formed, which NASA later made into movie clips.

In April 2009, Spirit got stuck in a patch of Martian sand. Engineers worked to try and free the rover but, over the next few months, it became clear that the machine wasn't going to budge. Without the ability to move, Spirit couldn't tilt its solar panels toward the sun and slowly began to lose power. NASA gave up contact with Spirit in 2011, after the rover's electronics had likely become permanently damaged by Mars' harsh winter. The rover was intended for a 90-day mission but lasted for six years and drove 4.8 miles across the Martian surface. [Postcards from Mars: The Amazing Photos of Opportunity and Spirit Rovers]

When it came down to Mars, Opportunity made an unplanned hole-in-one landing directly inside a crater, later named Eagle Crater. The vehicle investigated the surrounding plains, coming across meteorites and rumbling over sand dunes. It sent back spectacular photos of tiny, iron-rich pebbles nicknamed "blueberries" that seem to suggest a watery past on Mars, though scientists are still scratching their heads over the full implications of these mysterious rocks. Together with its sibling, Spirit, Opportunity transformed our understanding of Mars; a place we once thought of as a dead, desert world has become a planet with a complex and interesting geological history that might have once contained conditions favorable to living organisms.

A global Martian dust storm that began May 30, 2018 and raged for four months likely covered the rover's solar panels in obscuring dust, causing NASA to lose contact with Opportunity. On Feb. 12, 2019, officials stopped trying to make contact with the deceased robot. Opportunity drove more than 28 miles (45 km) in the course of more than 14 years, farther than any vehicle on another world.

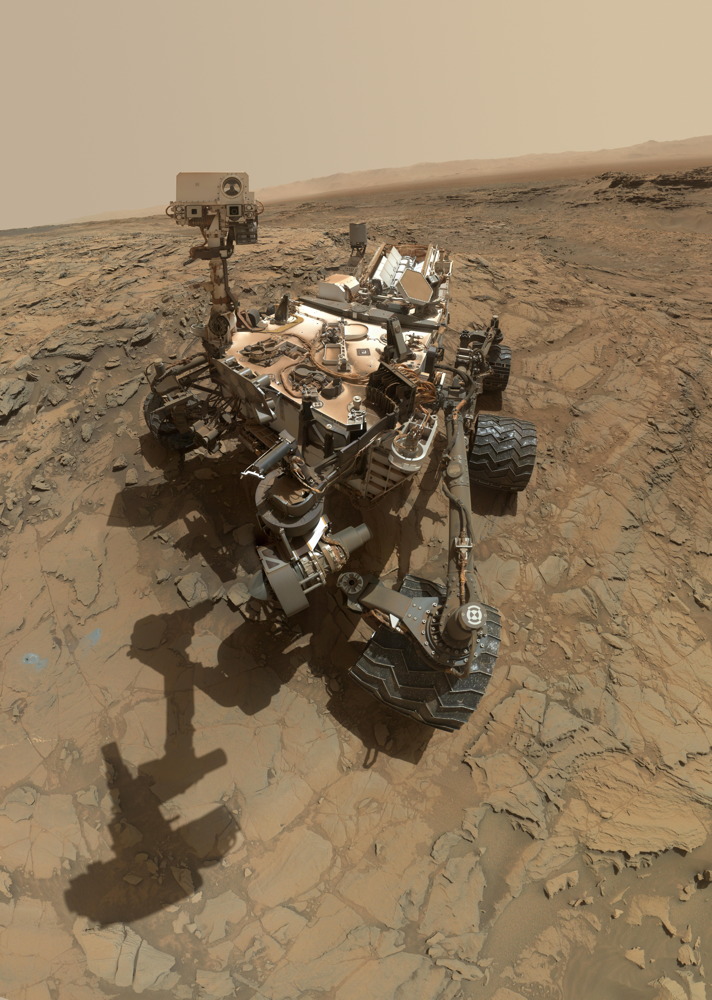

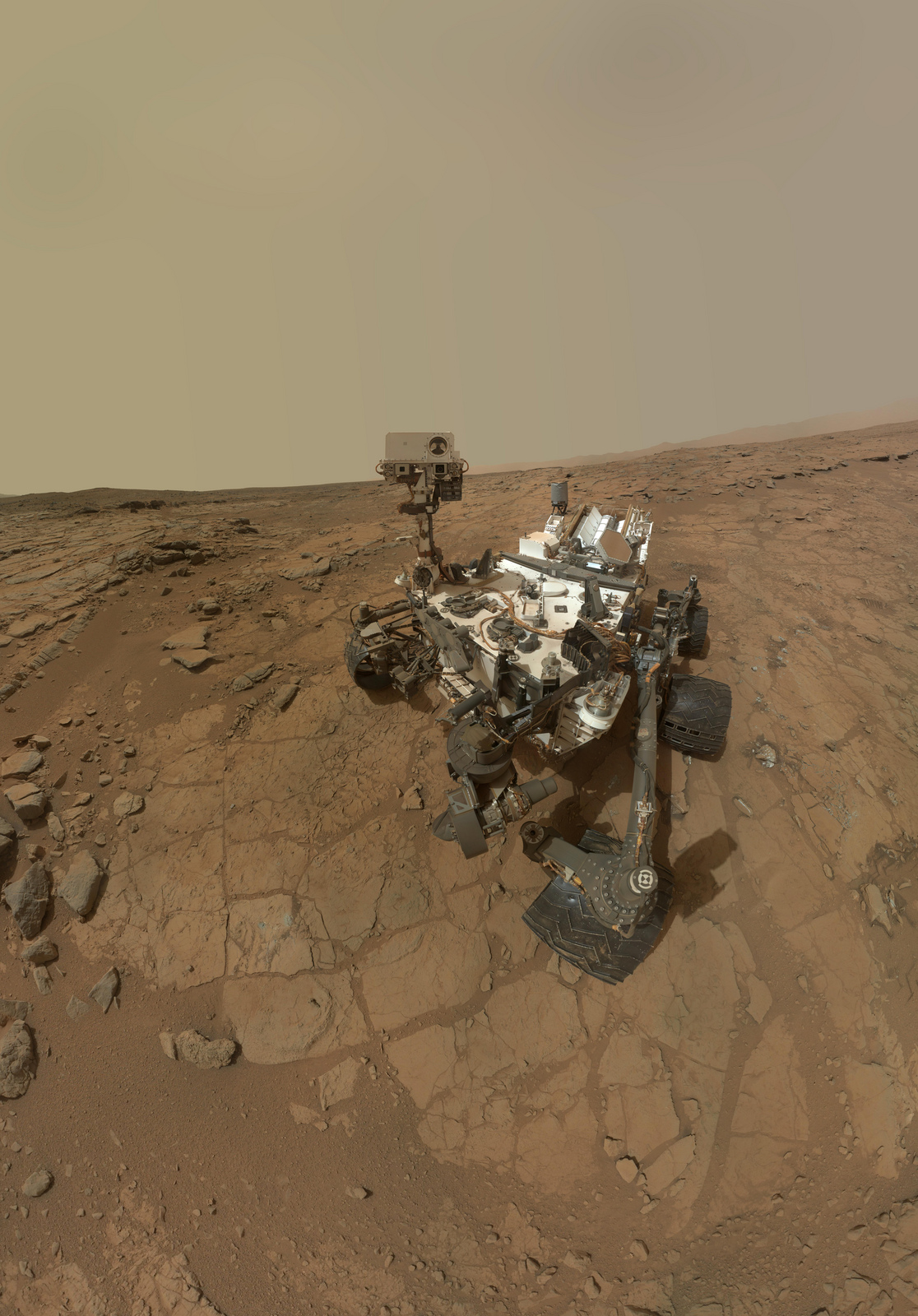

Curiosity

The most recent rover to touch down on Mars is Curiosity, which landed on Aug. 6, 2012. The 1-ton, SUV-size machine is the largest vehicle to reach the Martian surface, requiring an elaborate sky-crane mechanism to lower it down to the ground following an infamous "seven minutes of terror," during which NASA engineers couldn't contact the robot. Curiosity is the first rover that's not solar-powered; instead, it relies on a nuclear radioisotope thermoelectric generator, which produces electricity from the heat of plutonium-238's radioactive decay. It can travel about 660 feet (200 m) per day.

Curiosity's main scientific goals are to determine if Mars was ever capable of hosting living organisms. From its landing site in Gale Crater, it has investigated the surface using an entire laboratory's worth of instruments, including multiple cameras; spectrometers that can determine the chemical composition of rocks; weather and atmospheric sensors; and even a laser that can vaporize and then analyze chunks of Mars. In 2018, Curiosity discovered organic materials, the building blocks of life, in 3.5-billion-year-old Martian rocks. The rover is also a media darling, with a penchant for snapping selfies.

NASA's newest rover has been traveling for more than six years, and nobody knows how long Curiosity will last. Its nuclear battery could keep going for six to nine more years, or perhaps longer.

Perseverance

NASA's newest Mars rover, Perseverance, was named and launched in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic on July 30, 2020 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The rover, which arrived successfully at the Red Planet on Feb. 18, 2021, will hunt for signs of habitable environments on Mars while searching for signs of past microbial life. The robotic traveler will also cache a series of samples that can be returned to Earth by a future campaign.

Read more: Percy's "Seven Minutes of Terror," or the robot's thrilling landing on Mars

Perseverance has an initial mission duration of at least one Martian year, or 687 Earth-days. If it looks familiar, that's because the robotic explorer is largely a twin of Curiosity. Roughly 85% of the new rover's mass is "heritage hardware," saving time, expense and risk in the rover's design.

The new stuff is mostly a suite of cutting-edge instruments added to the 10 feet long rover. At 2,314 lbs. (1,050 kilograms), Perseverance weighs less than a compact car. But it packs a lot into that frame. Using an X-ray spectrometer and an ultraviolet laser, Perseverance will seek out biosignatures from the past on a microbial scale. A ground-penetrating radar will be the first rover instrument to look under the surface of Mars, mapping layers of rock, water and ice up to 33 feet (10 m) deep.

Future rovers

China's first mission to reach Mars, Tianwen-1, is currently in orbit around the planet. The lander and rover will attempt to descend to the surface sometime in May or June of 2021, joining the fleet of NASA rovers already scattered across Mars. The rover will complement the Tianwen-1 orbiter's distant investigation of surface soil characteristics and water-ice distribution with its own Subsurface Exploration Radar. It will also analyze surface material composition and characteristics of the Martian climate and environment on the surface.

Because of unforeseen parachute problems and complications due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Space Agency in collaboration with the Russian space agency Roscosmos postponed the launch and therefore the arrival of their ExoMars 2020 rover. That rover will carry the name of British scientist Rosalind Franklin, and will feature a drill that can penetrate up to 6 feet (2 m) below the Martian surface in order to search for potential signatures of life on Mars.

Additional resources:

- Read about and see pictures of more than 40 missions to Mars.

- Follow the rover Curiosity as it makes its way across the Martian terrain.

- Learn more about Mars at NASA's Solar System Exploration website.

This article was updated on Feb. 18, 2021 by Space.com Reference Editor Vicky Stein, with new information on the Tianwen-1, ExoMars 2020, and Perseverance rovers.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Adam Mann is a journalist specializing in astronomy and physics stories. His work has appeared in the New York Times, New Yorker, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike. Follow him on Twitter @adamspacemann or visit his website at https://www.adamspacemann.com/.