NASA: Huge Mars Rover's Sky Crane Landing Was 'Least Crazy' Idea

The stunningly intricate series of maneuvers that will drop NASA's Curiosity rover onto the Martian surface Sunday (Aug. 5) looks pretty reasonable when you consider the alternatives, experts say.

Late Sunday night, the 1-ton Curiosity rover's spacecraft will barrel into the Red Planet's atmosphere going about 13,000 mph (21,000 kph). A huge parachute will deploy about 7 miles (11 kilometers) above the ground, slowing the vehicle down to 200 mph (320 km) or so. Rocket engines will then fire, reducing the craft's descent speed to less than 2 mph (3.2 kph).

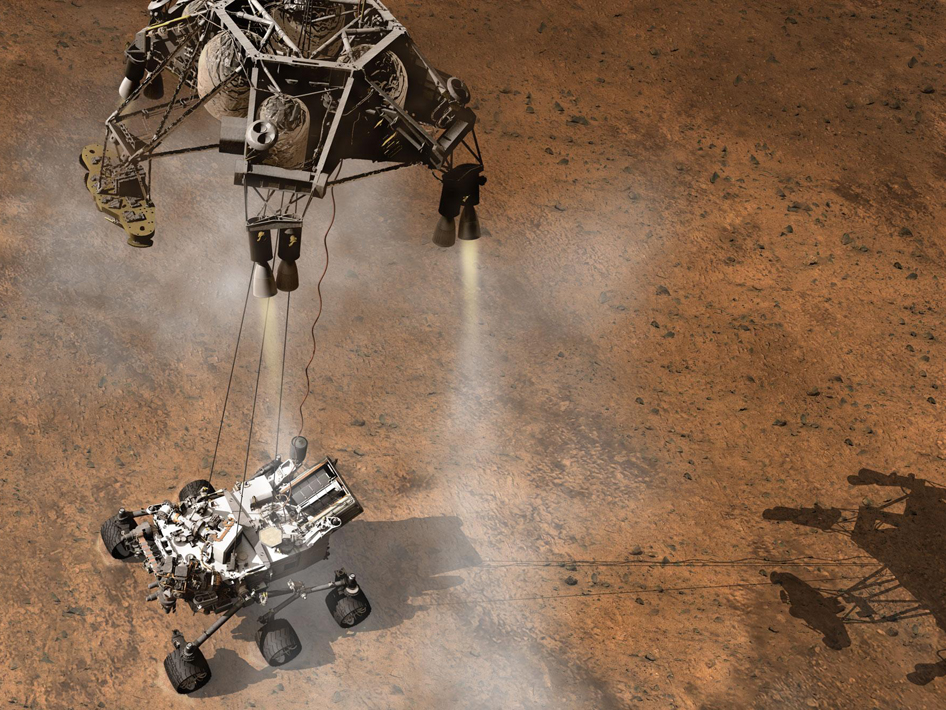

Finally, the $2.5 billion rover will be lowered to the surface on cables. When Curiosity's six wheels hit the red dirt inside Mars' huge Gale Crater, its "sky crane" descent stage will fly off and crash-land intentionally a safe distance away. NASA has dubbed the maneuver "seven minutes of terror."

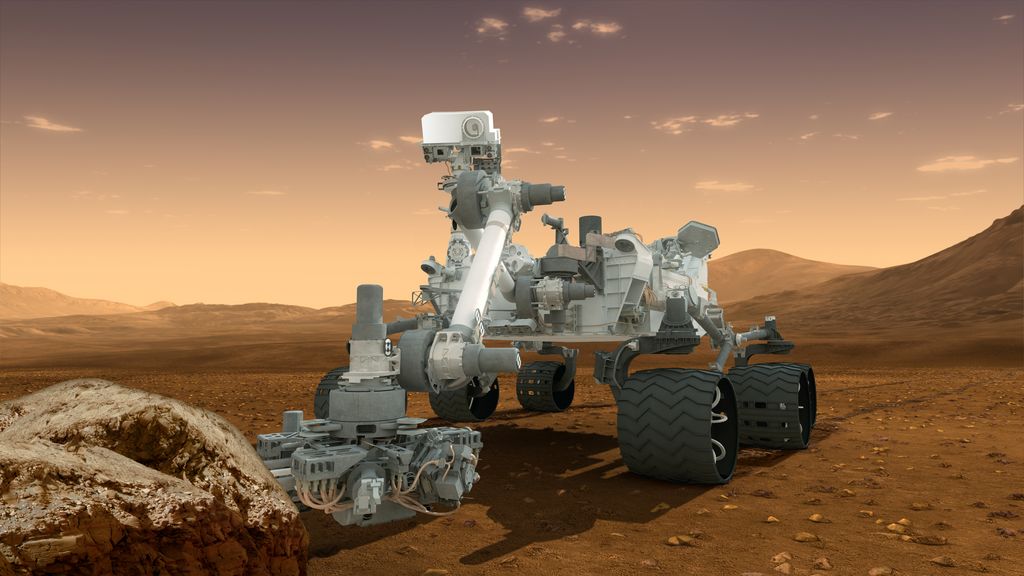

Curiosity is the largest rover ever sent to explore another world, and this sequence was designed specifically to accommodate its huge bulk. The landing method may seem incredibly complicated, but the mission team is confident it will work — and it was the best available option, engineers said. [Photos: How Curiosity's Crazy Landing Works]

"It looks a little bit crazy. I promise you, it is the least crazy of the methods you could use to land a rover the size of Curiosity on Mars," Adam Steltzner, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., told reporters today (Aug. 2). Steltzner is entry, descent and landing phase lead for Curiosity's mission, which is known as the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL).

To illustrate the point, Steltzner discussed the two chief alternatives to the sky crane Mars landing system. The first of these, he said, was putting Curiosity down on legs, as NASA did on Mars with its two Viking landers in the 1970s and the Phoenix lander in 2008.

But the team determined that Curiosity — which aims to determine if the Gale Crater area can, or ever could, support microbial life — is just too big to land safely on legs.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When you stick a rover the size of Curiosity on the deck of a legged lander, it becomes very unstable, and you need to land on a flat-top spot to be able to make that happen," Steltzner said.

The other leading alternative was to send Curiosity bouncing across the Martian landscape cushioned inside airbags. The twin Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers landed this way in January 2004.

Again, however, Curiosity's heft nixed this idea. It weighs about five times as much as either Spirit or Opportunity.

"Unfortunately, we don't have fabric here on Earth strong enough to build airbags that would work for a rover the size of Curiosity," Steltzner said. "The bags would shred, not giving Curiosity any protection."

So MSL's entry, descent and landing team was left with the sky crane method, which has performed well in all of the engineers' simulations.

"We've become quite fond of it, and we're fairly confident that Sunday night will be a good night for us," Steltzner said.

Curiosity is due to land on Mars at 10:31 p.m. PDT on Sunday, Aug. 5 (1:31 a.m. EDT, 0531 GMT on Aug. 6).

Visit SPACE.com for complete coverage of NASA's Mars rover landing Sunday. Follow senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwallor SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebookand Google+.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.