Another Extrasolar Planet Possibly Imaged

Astronomerssay they have directly imaged a giant exoplanet orbiting its parent star. Theannouncement comes on the heels of two other reports this month of directimages of planets beyond our solar system.

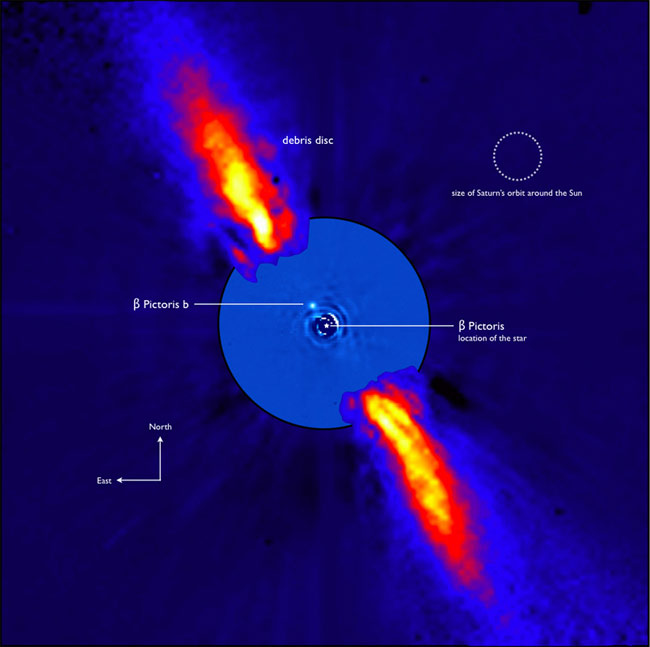

The newinfrared image shows the object as a speck of light near the star BetaPictoris, which is 70 light-years from Earth, toward the constellationPictor.

"Wecannot yet rule out definitively, however, that the candidate companion couldbe a foreground or background object," said study team member Gael Chauvinof Grenoble Observatory in France. "To eliminate this very smallpossibility, we will need to make new observations that confirm the nature ofthe discovery."

Chauvin andother French astronomers discovered the candidate planetusing the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope. Thepossible planet is estimated to weigh about eight times the mass of Jupiterwith an orbit of eight astronomical units (AU) from its star, where one AU isthe average Earth-sun distance.

AstrophysicistSara Seager of MIT, who was not involved in the latest discovery, said whilethe possibility is exciting, another more convincing image of the object is inorder. "We want to make sure it's moving together with the star,"Seager said.

Anotherimage would show whether the star is moving at a different speed relative tothis object and other background objects or if the star and planet are movingtogether (which would help to confirm this is indeed a planet).

Astronomershad thought a planet could be responsible for irregularities seen in the debrisdisk, first imaged in 1994, surrounding Beta Pictoris. As a planet treks aroundits star, the planet jostles and tugs on pieces of dust and debris, shaping thedisk.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"BetaPic has been teasing astronomers for the past two decades with hints of anorbiting planet," said University of California, Berkeley, astronomer PaulKalas, who was not directly involved with the study. Kalas led a team ofastronomers who reported this month the first visible-light snapshotof a single-planet system around the star Fomalhaut.

Theresearchers say the object does explain the warped disk. "The candidatecompanion has exactly the mass and distance from its host star needed toexplain all the disk's properties," said team leader Anne-Marie Lagrangeof the Grenoble Observatory.

The teamtried to rule out other non-planet possibilities. For instance, they looked atimages taken by the HubbleSpace Telescope of the system, which would likely reveal background andforeground objects.

They alsoused three independent detection methods to rule out the possibility that thepoint source of light was just an artifact of the observing instrument.

"Overall,this is an exciting discovery that could be verified in just a few weeks timesince Beta Pictoris is a bright star visible during the winter months,"Kalas told SPACE.com.

Actually,Lagrange said the planet might not be visible with their instruments currently,because of the inclination of the orbit and how it is aligned. So from ourperspective on Earth, the planet could travel too close to its star to bevisible.

Thediscovery will be detailed in a forthcoming letter to the editor in the journalAstronomy and Astrophysics.

- Video: Alien Habitable Zone

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Video: Planet Hunter