The Best Space Stories of 2018!

As 2018 wraps up, it's time to review some of the biggest space science stories of the year. From incredible exomoons to masterful missions to groovy gravitational waves, the last 12 months have been packed with science. Here are the top stories of the year.

Be sure to tell us your favorite science stories in the comments! [Related: The Greatest Spaceflight Moments of 2018!]

A Year of Missions

The year 2018 saw the beginning of some missions, and the end of others. Even a long-ago-launched spacecraft from the 1970s chimed in to make news!

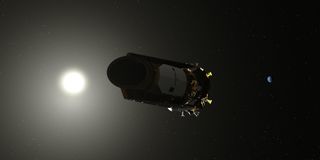

The end of Kepler

After almost a decade of hunting for planets around other stars, NASA's Kepler spacecraft was decommissioned on Nov. 15, after the legendary planet hunter finally ran out of fuel. Kepler made history by discovering thousands of exoplanets, dramatically increasing the number of known worlds circling other stars. By 2008, the year before Kepler's launch, scientists had confirmed the existence of 340 exoplanets, according to data from the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Kepler has contributed another 2,328 worlds, with an additional 2425 candidates waiting to be confirmed.

The $700 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009, its goal to determine how common Earth-like planets are in our Milky Way galaxy. The spacecraft stared at more than 150,000 stars simultaneously, monitoring dips in their brightness that could be caused by the passage of a planet between Earth and a star. In 2013, the second of the spacecraft's four reaction wheels failed, ending the original mission and giving rise to a new mission known as K2, where it surveyed different parts of the sky.

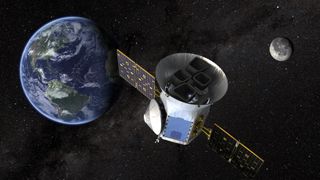

The rise of TESS

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Even as Kepler faded, NASA began a new planet-hunting mission. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) launched into orbit around Earth on April 18 and began gathering science data on July 25. By September, it had already announced its first two planets, the start of a new bonanza. During its two years of observation, TESS will observe almost the entire sky, focusing on the 200,000 brightest stars. In that brief span, researchers estimate the telescope will find about 10,000 new exoplanets, including some the size of Earth.

InSight on Mars

This year brought milestones for a planet inside our solar system, too. NASA's InSight lander touched down safely on Mars on Nov. 26. Like TESS, InSight began its interplanetary journey in 2018. Its May 5 launch was the first-ever liftoff of an interplanetary mission from the U.S. West Coast. Two tiny cubesats launched with the spacecraft and trailed it to the Red Planet, providing near-real-time updates on the mission and becoming the first small satellites to leave Earth's immediate orbit. When it arrived at Mars, InSight touched down on the Elysium Planitia, a smooth flat plain. InSight is a lander, rather than a rover: It will remain stationary over its mission.

Over the next two Earth years, the lander will probe the composition and interior structure of the Red Planet in unprecedented detail. A heat probe will burrow up to 16 feet (5 meters) beneath the surface, while a trio of incredibly precise seismometers will monitor the planet for marsquakes, meteorite impacts and other activity. The instruments are still waiting to be deployed, and it will take another month to calibrate them for use on Mars. But 2018 saw the lander touch down safely, a crucial step in its investigation and one that not all Martian missions accomplish.

Hard times for Opportunity

NASA's longest-lived Mars rover, Opportunity, lost contact with Earth on June 10. A powerful globe-spanning dust storm hid the sun, causing the rover to retreat into a low-power mode. Not until Sept. 11 was the spacecraft able to receive enough light to have begun generating power. After listening daily for over a month after that, team members scaled back their efforts to hear signals for the rover. NASA will continue to passively listen for the rover until the end of January 2019.

Opportunity landed on Mars with its sister robot, Spirit, in 2004. The pair had a life expectancy of 90 Martian days, each about 40 minutes longer than an Earth day, on the surface, with dust expected to slowly bury them. But Spirit lasted seven years, while Opportunity was approaching its 15th year when the storm hit. That makes the spacecraft the longest-lived Mars rover in history. In its 12th year, Opportunity had traveled a marathon-exceeding 26.5 miles (42.65 km), farther than any robot has traveled on the surface of another world.

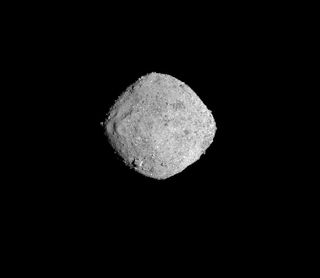

Asteroid arrivals

Mars wasn't the only spot in space to receive visitors this year. NASA's OSIRIS-REx, which launched in September 2016, arrived at the asteroid Bennu in December. With a goal of helping scientists to improve their understanding of the solar system's history, OSIRIS-REx will eventually return a sample from Bennu back to Earth in 2023. But before it begins its return flight, the spacecraft will study the 1,640-foot-wide (500 meters) near Earth asteroid. Only a week after its arrival, researchers announced that OSIRIS-REx had found signs of hydrated minerals that suggest liquid water was once plentiful inside the asteroid's parent body.

And another space agency got in on the asteroid-visiting fun: Japan's Hayabusa2 spacecraft touched down on the asteroid Ryugu in October, scooping up a sample that will also return to Earth. Hayabusa2 launched on Dec. 2, 2014. It arrived at Ryugu on June 27, 2018, and began a 1.5-year-- long survey of the asteroid. In September, the spacecraft dropped two tiny hopping robots that sent back pictures of the asteroid's surface, as well as a larger lander that briefly gathered measurements. In 2019, Hayabusa2 will descend to the asteroid's surface to retrieve a sample that will land in Australia in 2020.

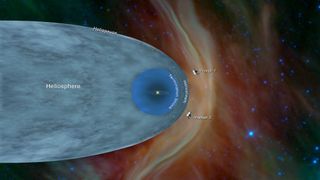

Voyager 2 goes interstellar

In November 2018, NASA's Voyager 2 probe crossed the boundary into interstellar space. Launched in 1977, the spacecraft visited all four of the giant planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — and discovered 16 moons, as well as phenomena like Neptune's strangely shifting Great Dark Spot, the cracks in the ice shell of Jupiter's moon Europa and ring features at every giant world.

Unlike Voyager 1, which crossed the heliopause — the bubble of charged particles from the sun that influences the environment of the solar system — in 2012, Voyager 2 carries two onboard instruments that can track particles as they collide with the spacecraft. That means Voyager 2 will collect not just new data but a new type of data, NASA officials said.

Martian Science

With six orbiters, one-and-a-half rovers, and a lander, Mars received a lot of press in 2018. From lakes to organics to massive dust storms, the Red Planet had a way of keeping all eyes turned its way.

Organics and oxygen on Mars

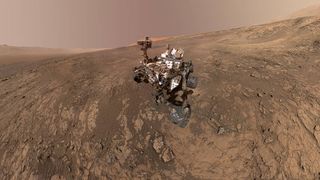

This summer, researchers reported that NASA's Curiosity rover found a variety of organic molecules, the carbon-based building blocks of life as we know it, in 3.5-billion-year-old Martian rocks. Researchers looked closely at samples of the first two Mount Sharp rocks Curiosity drilled in 2014 and 2015. They found several new organics, as well as a number of molecules that are probably fragments of much larger compounds rich in carbon. Although not evidence for life, it's possible that they came from ancient life or at least provided a source of food for tiny organisms of the past.

In a separate study published in October 2018, researchers reported that salty Martian water could contain enough oxygen to support life. Researchers modeled the oxygen-harboring potential of near-surface brines, calculating how much dissolved molecular oxygen they could contain at various points around the Martian planet. They found that the brines could hold enough oxygen to support aerobic microbial life pretty much all across the planet. While not a direct detection, the study raises interesting points about the potential habitability of Mars today.

Liquid water under Mars ice

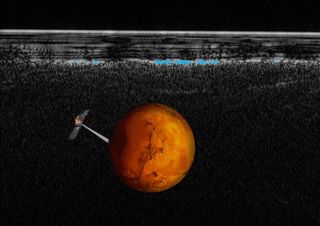

In July, researchers announced the discovery of a large underground lake hidden beneath the planet's surface. The lake sits beneath a mile (1.6 km) of ice at the southern pole. Using an instrument on board the European Space Agency's Mars Express, which has orbited the Red Planet since 2003, researchers used radar pulses to study the planet's interior structure. The radar signals bounce back to the orbiter differently depending on the material they encounter. And beneath the southern pole, the radar signals found signs of a hidden lake.

According to the radar, the lake is no more than 12.5 miles (20 km) across. Researchers can't determine exactly how deep the lake is, but they confirmed it has a depth of at least 3 feet (1 meter). But don't hold out for fresh water: To remain liquid in the freezing temperatures beneath the ice, the lake would need to be quite salty, the researchers said.

Epic Martian dust storm

For the first time in over a decade, a massive global dust storm wrapped itself around the planet Mars. The storm grew larger over a period of several weeks, and by June 20, NASA officials were classifying it as a global weather event.

Originally detected on May 30 by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the storm grew to be larger than the last global dust storm, a 2007 gale that Opportunity survived. It's more similar to a dust storm spotted by the Viking 1 lander in 1977. The storm began to die down in July, and by the end of August, normal conditions were just around the corner.

Exploring the Universe

From distant stars to dark matter, gravitational waves to exomoons, 2018 has been a stellar year for astronomy beyond the solar system.

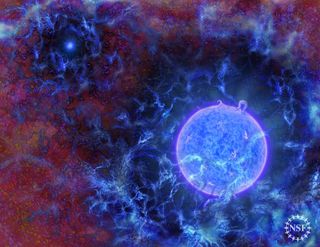

Dark matter and the universe's first stars

The universe's first stars may have revealed a major clue about dark matter. In February, researchers reported that they had spotted the fingerprints of the universe's first stars. The signal was twice as intense as predicted, suggesting that either the hydrogen gas that filled the early universe was significantly colder than expected or background radiation levels were hotter than the radiation left over from the Big Bang. The chilling effect may have come from dark matter.

While ordinary matter has spent the 13.8 billion years heating up, dark matter has been cooling down. When particles of both collide, heat would naturally move from the warmer body to the colder one, causing the warmer body to cool ever so slightly. With nothing else to heat the gas in the early universe, it would quickly cool down as it interacted with dark matter. In today's universe, that effect would be drowned out by heat from stars and X-ray effects from objects like black holes.

The most distant star ever spotted

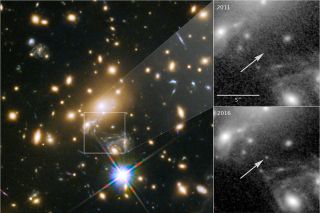

In April, astronomers reported that NASA's Hubble Space Telescope had spotted the most distant ordinary star ever observed. (Stars that explode into supernovas can be seen from farther away.) Nicknamed Icarus, the star lies 9 billion light-years from Earth, so its light took 9 billion years to reach us. By comparison, the age of the universe is about 13.8 billion years.

Astronomers found the star through gravitational lensing. By using a massive object like a galaxy cluster to bend light, gravitational lensing serves as a magnifying glass to make dim objects appear much brighter from Earth's perspective. Usually an object can be magnified up to 50 times, but a rare alignment between Hubble and Icarus allowed the newfound star to be magnified more than 2,000 times.

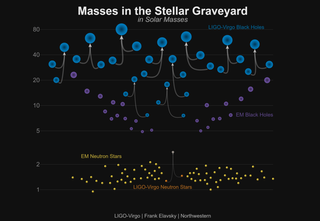

LIGO spots 4 new gravitational wave signals

The U.S.-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and its European counterpart Virgo unveiled four new detections of gravitational waves in December. The massive collisions are produced as pairs of black holes or neutron stars — both incredibly dense objects left behind after a star explodes — draw close to one another. As they dance, they cause gravitational waves to ripple outward until the objects eventually collide.

The new announcement marks the largest batch of gravitational-wave detections released at one time, bringing the total to 11 in only a handful of years. It includes an event that is both the most massive and the most distant collision to date. The quadruple discovery didn't come from new detections, as both LIGO and Virgo have been down for upgrades since August 2017. Instead, the signals were found as scientists looked back through detections made between Aug. 25, 2017, and Nov. 30, 2018.

A wealth of mysterious fast radio bursts

Intense emissions of radio light called fast radio bursts (FRBs) can pack as much energy as a century's worth of solar activity into brief, millisecond-long bursts. Their source remains a mystery. But in October, astronomers announced the detection of 20 previously undiscovered FRBs, including the closest one to Earth and the brightest one ever seen. That ups the total to just over 50, with the first detection coming in 2007.

Using the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), a network of 36 radio dishes in Western Australia, researchers turned up 20 new FRBs over a region of the sky about 1,000 times larger than the full moon. The new research suggests that FRBs are coming from the other side of the universe, rather than from our own galactic neighborhood.

The first exomoon?

Moons are common in the solar system but have remained tantalizingly out of sight during the hunt for exoplanets. That may have changed this year. In October, astronomers announced the first evidence for an exomoon, a Neptune-size satellite orbiting the gas giant Kepler-1625b. While the observations don't constitute a definitive detection, they provide enough information to allow other astronomers to determine if a moon can be teased out.

The new results emerged from a focused exomoon hunt using data from Kepler. While studying exoplanets with relatively wide orbits — planets that take at least 30 Earth days to make an orbit —the astronomers found odd deviations around 1625b, a planet roughly three times as massive as Jupiter orbiting a sun-like star. Although last year saw a leak of the results, this year the researchers were able to publish their findings in a peer-reviewed journal, a rigorous part of the scientific method.

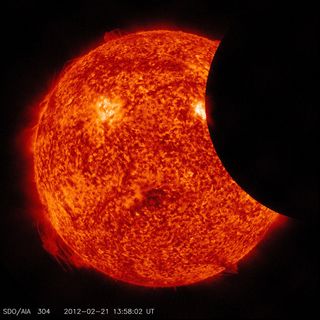

The summer's triple eclipse

Back on Earth, non-scientists were able to enjoy three eclipses over the course of a month. On July 13, a partial solar eclipse crossed the ocean between Australia and Antarctica. The best place to see the eclipse was on Antarctica's Peterson Bank, home to an emperor penguin colony. A total lunar eclipse on July 27, the longest lunar eclipse of the 21st century. That eclipse lasted 1 hour and 43 minutes, only 4 minutes shorter than the longest possible such event calculated by astronomers. Observers in much of Africa, the Middle East, southern Asia and the Indian Ocean region caught an eyeful. The triple-header wrapped up with a partial solar eclipse on Aug. 11, visible to those living in northern Europe, a large portion of central and eastern Asia, and northern and eastern Canada.

While a solar or lunar eclipse usually follows its counterpart by two weeks, a triple play is not out of the question. During this summer's lunar eclipse, the moon passed just to the north of the middle of Earth's shadow, reaching the descending node of its orbit — the point where it crosses the ecliptic going from north to south — just 138 minutes after it becomes a full moon, resulting in a nearly central total eclipse. As a result, the pair of new moons before and after the full moon dance just close enough to the moon's opposite ascending node to allow the moon to partially eclipse the sun both times.

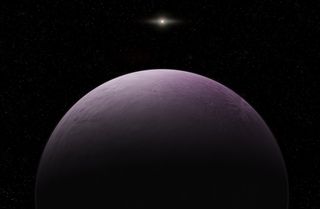

A new solar-system friend

As 2018 came to a close, astronomers announced the newest known member of our planetary collection, a potential dwarf planet that is the most-distant body ever observed in the solar system. Nicknamed " Farout," the object's official designation is 2018 VG18. Farout orbits more than 100 times the distance from the Earth to the sun, taking more than a thousand years to take a single trip around our star. Preliminary research suggests it's a round, pinkish dwarf planet about 310 miles (500 km) across.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter@NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at@Spacedotcom,FacebookGoogle+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd