Leak in Mars Rover Curiosity's Wet Chemistry Test Finds Organics

An unexpected leak of a chemical designed to tag complex organic molecules in samples collected by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity appears to have serendipitously done its job, scientists reported on Tuesday (March 17).

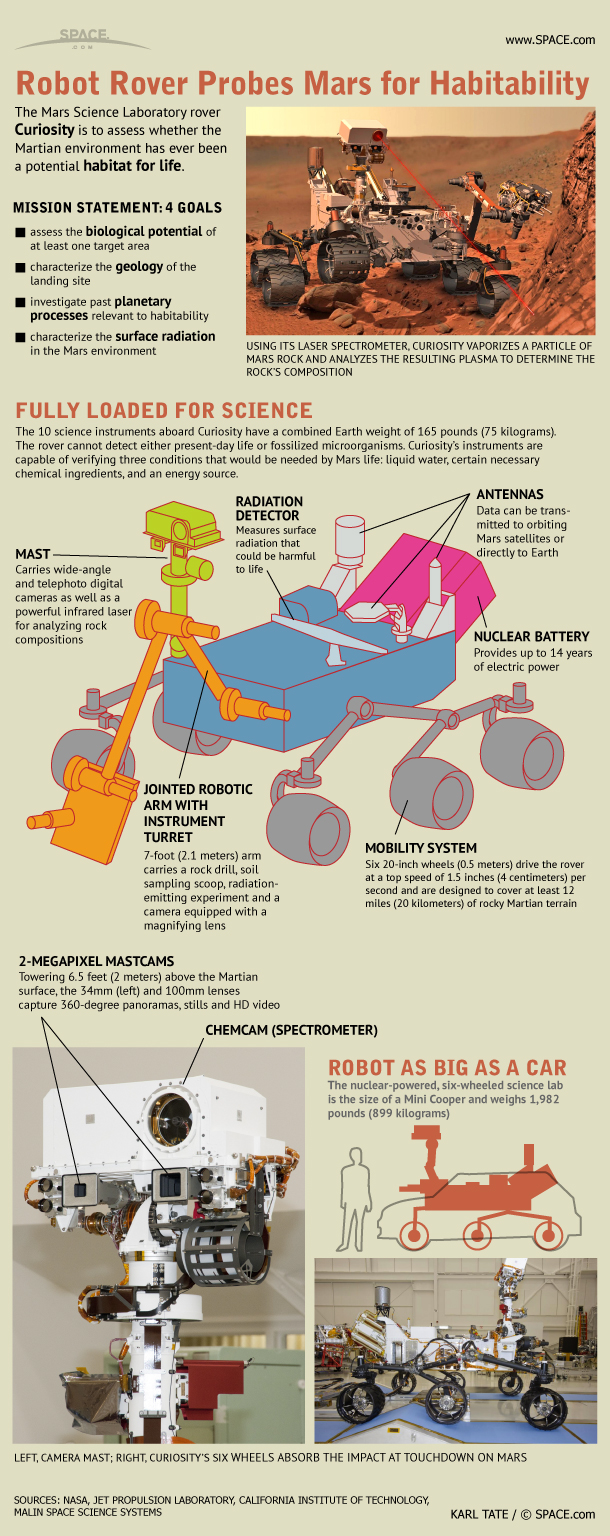

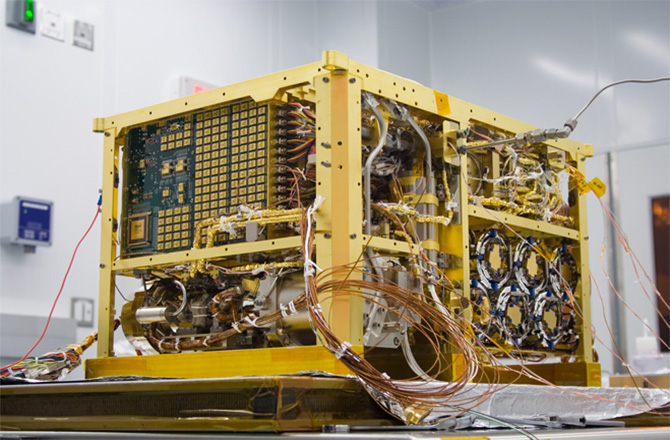

Curiosity's onboard laboratory includes seven so-called "wet chemistry" experiments designed to preserve and identify suspect carbon-containing components in samples drilled out from rocks.

Top 10 Space Stories of 2014: Readers' Choice

None of the foil-capped metal cups has been punctured yet, but vapors of the fluid, known as N-methyl-N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide, or MTBSTFA, leaked into the gas-sniffing analysis instrument early in the mission.

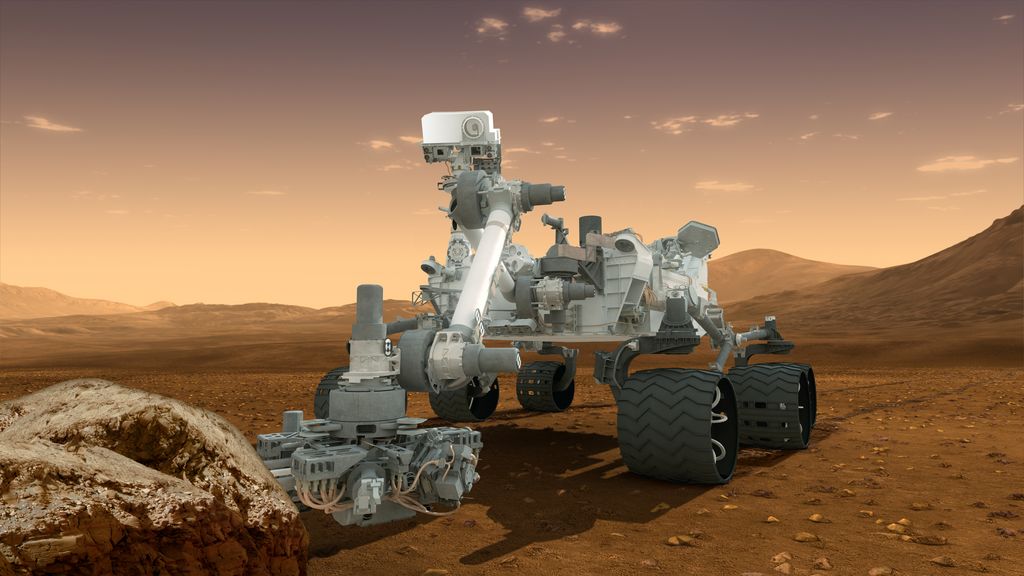

Curiosity landed in a 96-mile wide impact basin known as Gale Crater in August 2012 to determine if the planet most like Earth in the solar system has or ever had the chemistry and environments to support microbial life.

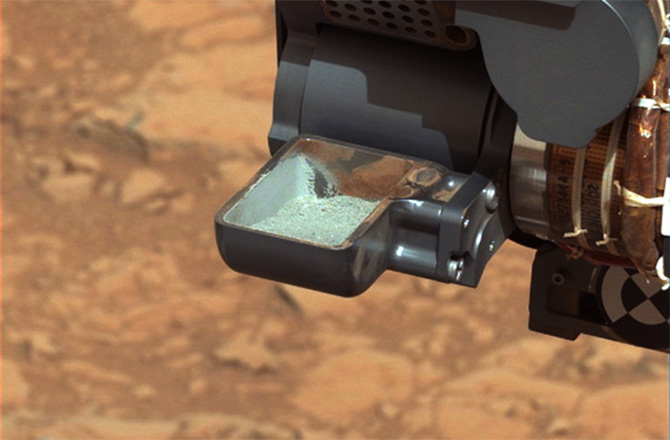

Scientists quickly fulfilled the primary goal of the mission, discovering sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon in powder Curiosity drilled out of an ancient mudstone in an area known as Yellowknife Bay.

BIG PIC: Curiosity's New Selfie Awash With Epic Mars Science

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That paved the way for a more ambitious hunt for complex organic molecules, an effort complicated by the MTBSTFA leak.

"This caused us a lot of headache in the beginning, frankly, because it has a lot of carbon in it and other (chemical) fragments that can break apart," Curiosity scientist Danny Glavin, with NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said on Tuesday at the Lunar and Planetary Science conference in Houston, Texas.

"We've turned this sort of bad thing into a good thing because we've learned how to work around this leak. We've actually used this vapor from this leak to carry out derivitization," he said, referring to the technique to tag organics.

Samples drilled out from Yellowknife Bay were stored inside the Sample Analysis at Mars, or SAM instrument, as the rover made its way over the next two years to Mount Sharp, a three-mile high mound of sediments rising from the floor of Gale Crater.

"These samples were just reacting with this MTBSTFA vapor, reacting with all that good organic stuff. That turned out to be a good thing," Glavin said.

NEWS: Viking Found Organics on Mars, Experiment Confirms

Scientists figured out how to extract the enriched vapor, collect it and analyze it in a way that preserved the organics.

In addition to analyzing the doggy-bagged sample that had been reacting with the MTBSTFA vapors for two years, scientists also were able to compare the results with residue from a sample that had been heated twice, effectively killing off any volatiles, but which also had been exposed to the vapors for two years.

Initial results show indigenous Mars complex organics in the fresh sample, though more work is needed to definitely peg the compounds.

NEWS: Mars Rover Finds Ancient Life-Supporting Lakebed

"This is really exciting stuff. We've got a mudstone on Mars in a habitable environment. There was a lake there at one point. We've got organic molecules, possibly some interesting ones, of astrobiological interest. Bottom line, this sample has an even more diverse set of organic compounds than we previously thought.

"Million dollar question? Is this biological or not. I wish I had an answer I can't tell you. We've got basically a few compounds that we're dealing with here. You probably need a lot more before you can start discriminating between biological and non-biological origin," Glavin added.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Irene Klotz is a founding member and long-time contributor to Space.com. She concurrently spent 25 years as a wire service reporter and freelance writer, specializing in space exploration, planetary science, astronomy and the search for life beyond Earth. A graduate of Northwestern University, Irene currently serves as Space Editor for Aviation Week & Space Technology.