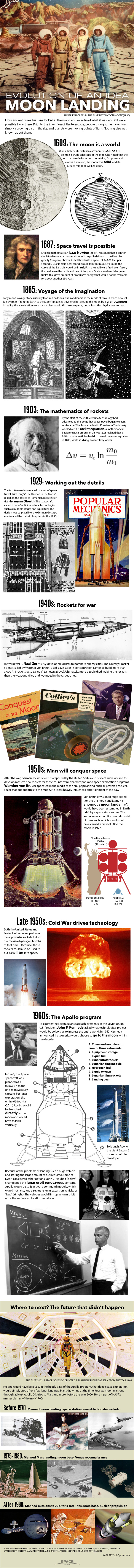

Destination Moon: The 350-Year History of Lunar Exploration (Infographic)

From ancient times, humans looked at the moon and wondered what it was, and if it were possible to go there. Prior to the invention of the telescope, people thought the moon was simply a glowing disc in the sky, and planets were moving points of light. Nothing else was known about them.

When 17th-century Italian astronomer Galileo first pointed a crude telescope at the moon, he noted that the orb had terrain including mountains, flat plains and craters. Therefore, the moon was solid, and its surface might be walked upon.

English mathematician Isaac Newton in the late 1600s reasoned that a cannon shell fired from a tall mountain would be pulled down to the Earth by gravity (diagram, above). A shell fired with a speed of 24,000 feet per second (7,300 meters per second) would fall continuously around the curve of the Earth. It would be in orbit. If the shell were fired even faster, it would leave the Earth and head into space. Such speed would require fuel with a great amount of propulsive energy that would not be available for about another 250 years.

Moon-Shots: Apollo Astronauts Remember

Early moon-voyage stories usually featured balloons, birds or dreams as the mode of travel. French novelist Jules Verne’s 1865 novel "From the Earth to the Moon" imagines travelers shot around the moon by a giant cannon. In reality, the acceleration from such a blast would kill the occupants, but at least the physics was correct.

By the start of the 20th century, technology had advanced to the point that space travel began to seem achievable. The Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1903 worked out his rocket equation, a mathematical basis for space propulsion. It was later realized that a British mathematician had discovered the same equation in 1813, while studying how artillery works.

The first film to show realistic scenes of space travel, Fritz Lang's "The Woman in the Moon" (1929), relied on the advice of Romanian rocket scientist Hermann Oberth. The spacecraft, called "Friede," anticipated real technologies such as multiple stages and liquid fuel. The design was so plausible, the German Gestapo confiscated the rocket blueprints in the 1930s.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In World War II, Nazi Germany developed rockets to bombard enemy cities. The country's rocket scientists, led by Wernher von Braun, used slave labor in concentration camps to build more than 3,000 A-4 rockets (also called V-2). Ultimately, more people died making the rockets than the weapons killed and wounded in the target cities.

After the war, German rocket scientists captured by the United States and Soviet Union worked to develop massive new rockets for those countries' nuclear weapons and space exploration programs. Wernher von Braun appeared in the media of the 1950s, popularizing nuclear-powered rockets, space stations and trips to the moon. His ideas heavily influenced entertainment of the day.

How the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Worked (Infographic)

Von Braun envisioned huge expeditions to the moon and Mars. His enormous moon lander would have been assembled in Earth orbit by a space station crew. The entire lunar expedition would consist of three such vehicles, and would have carried a crew of 50 to the moon in 1977.

By the late 1950s, both the United States and Soviet Union were developing ever more powerful rockets to loft the massive hydrogen bombs of that time. Of course, those rockets could also be used to put satellites in space.

In the early 1960s, to counter the spectacular space achievements of the Soviet Union, U.S. President John F. Kennedy asked what technological project would be so bold as to impress the entire world. In 1962, Kennedy announced that America would choose to go to the moon within the decade.

NASA's Mighty Saturn V Moon Rocket Explained (Infographic)

In 1960, the Apollo spacecraft was planned as a follow-up to the one-man Mercury capsule. For lunar exploration, the entire 66-foot-tall (20 m) Apollo would be launched directly to the moon and would have to land vertically.

Because of the problems of landing such a huge vehicle and storing the large amount of fuel required, some at NASA considered other options. John C. Houbolt (below) championed the lunar orbit rendezvous concept. Apollo would be split in two: a command module, which would not land, and a separate lunar excursion vehicle, or "bug." The vehicles would link up in lunar orbit once the surface exploration was done.

NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

NASA's 17 Apollo Moon Missions in Pictures

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Karl's association with Space.com goes back to 2000, when he was hired to produce interactive Flash graphics. From 2010 to 2016, Karl worked as an infographics specialist across all editorial properties of Purch (formerly known as TechMediaNetwork). Before joining Space.com, Karl spent 11 years at the New York headquarters of The Associated Press, creating news graphics for use around the world in newspapers and on the web. He has a degree in graphic design from Louisiana State University and now works as a freelance graphic designer in New York City.