Gallery: Planck Spacecraft Sees Big Bang Relics

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

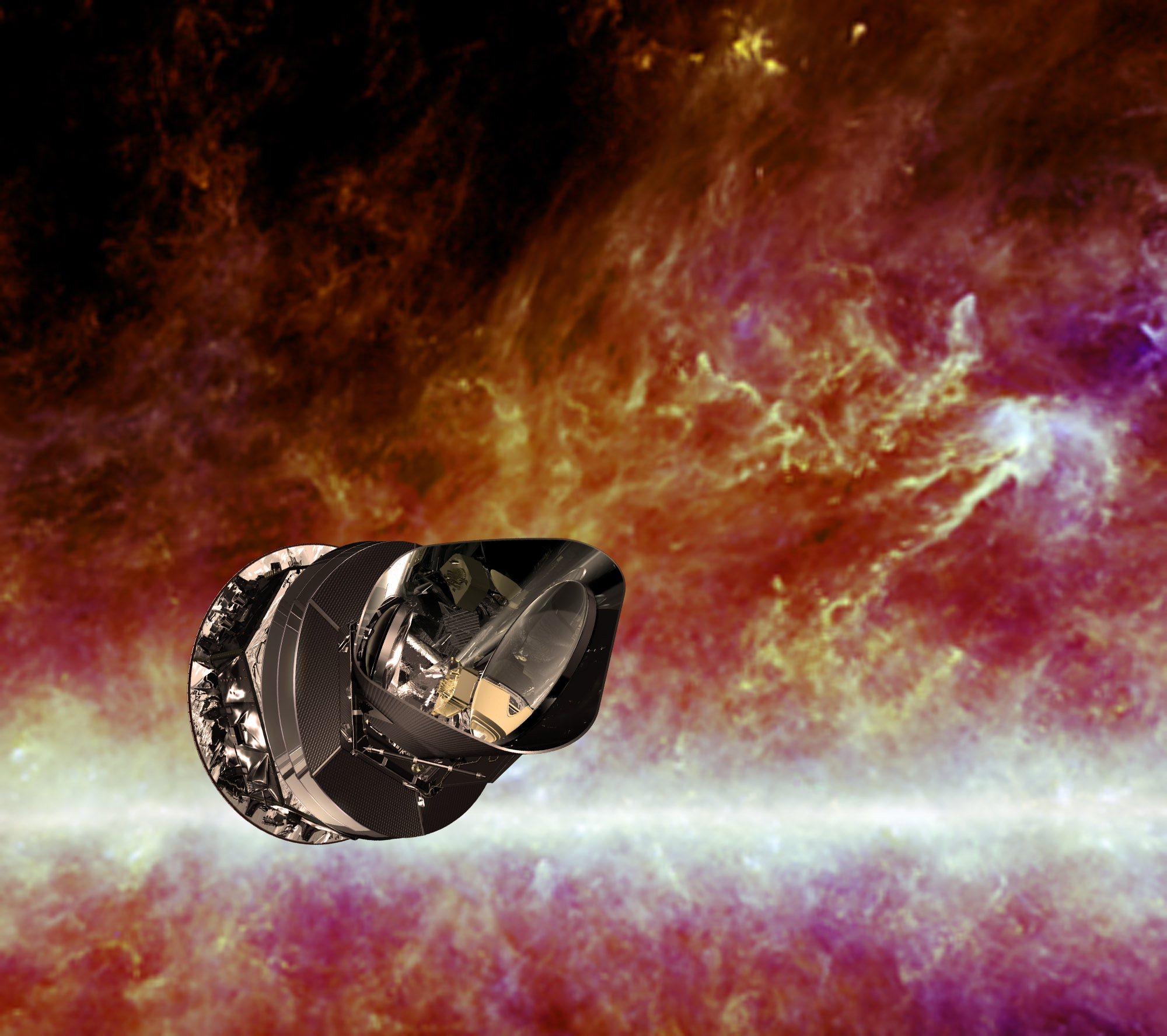

ESA's Planck Spacecraft

The European Space Agency's Planck observatory peered back into the universe's history to study the cosmic microwave background, the oldest light in the universe. See images from Planck's prolific mission in this Space.com gallery. Here: An artist's view of Planck with the cosmic microwave background as a backdrop.

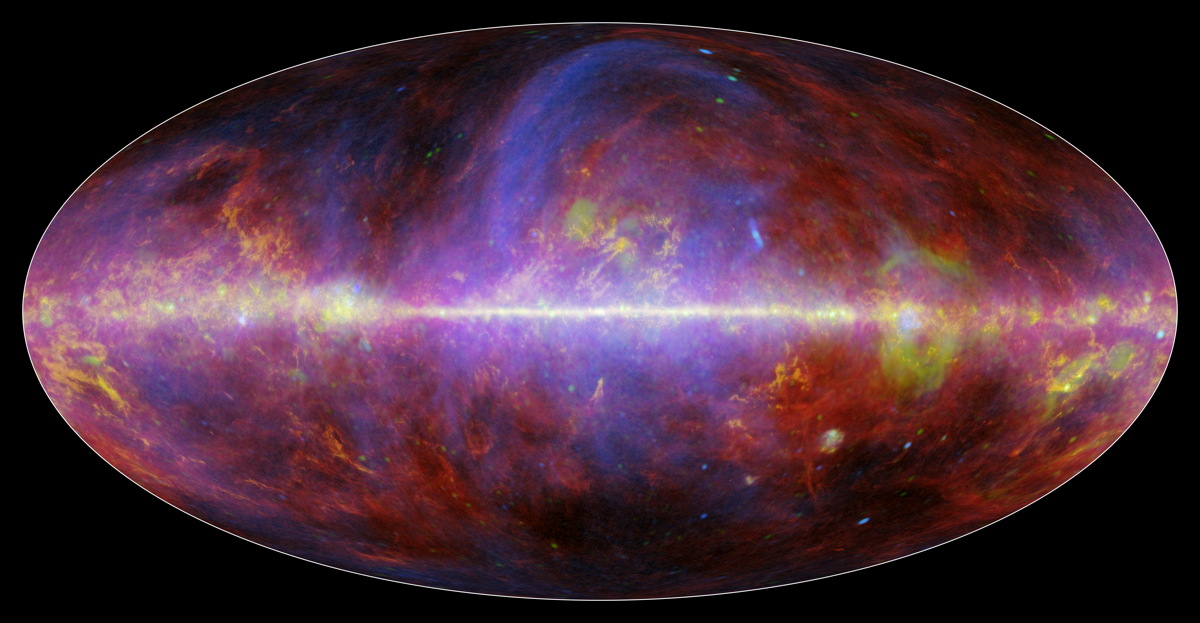

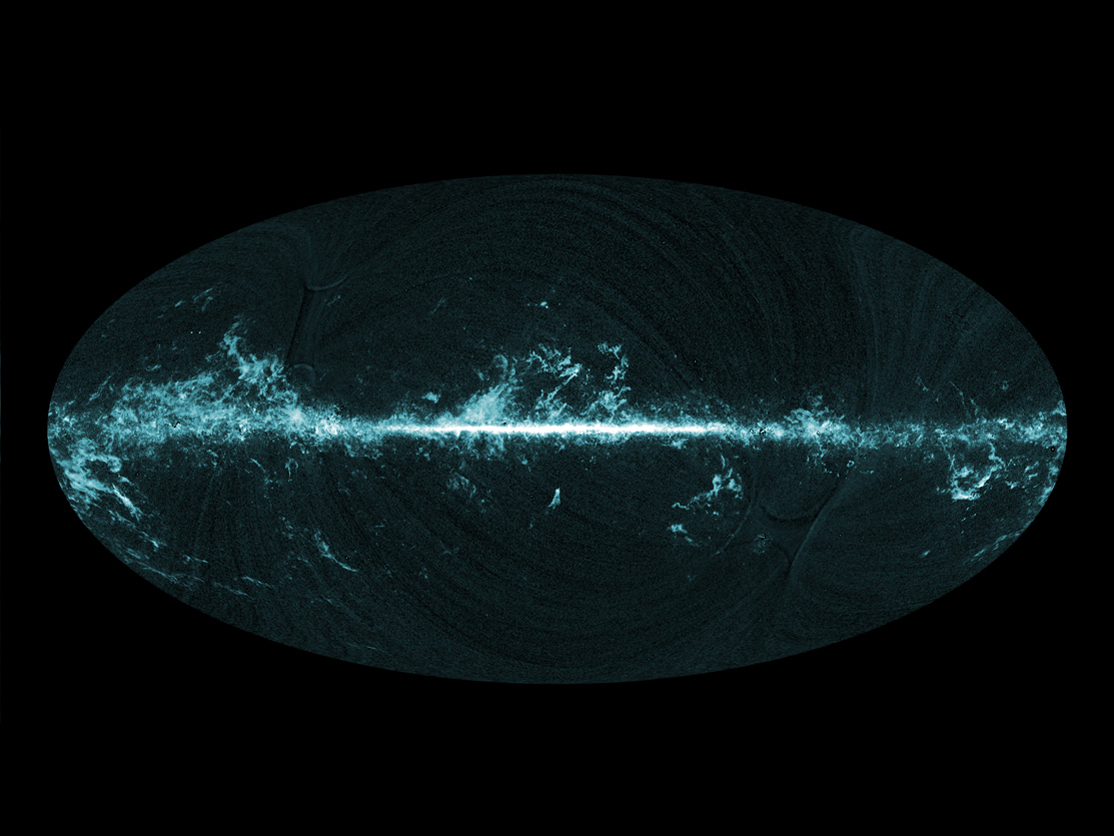

Milky Way Galaxy in Microwaves

A view of the Milky Way galaxy in microwaves, captured by the European Space Agency's Planck satellite. The different colors correspond to different elements, including gas, dust, and energetic particles. Read the Full Story.

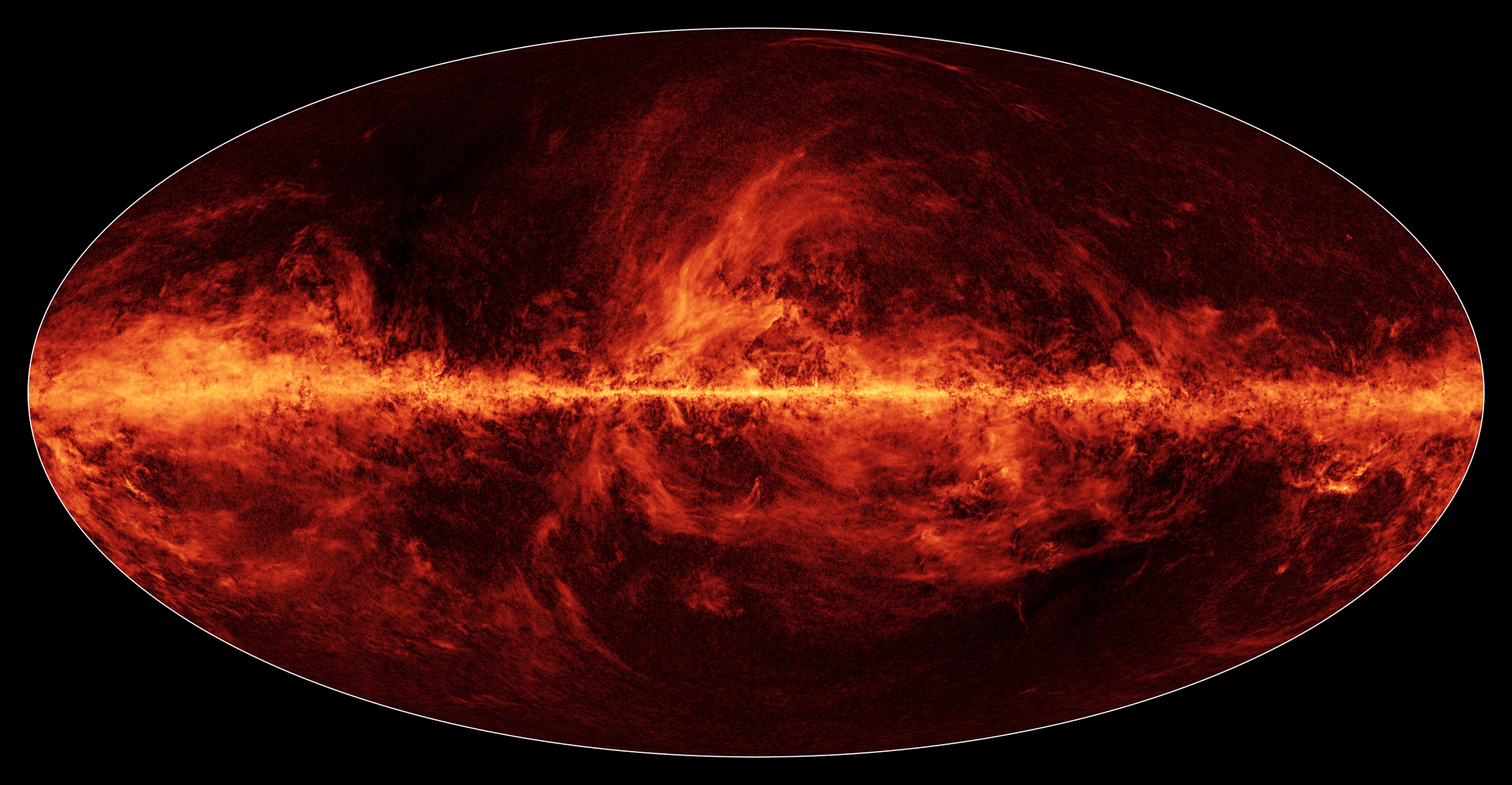

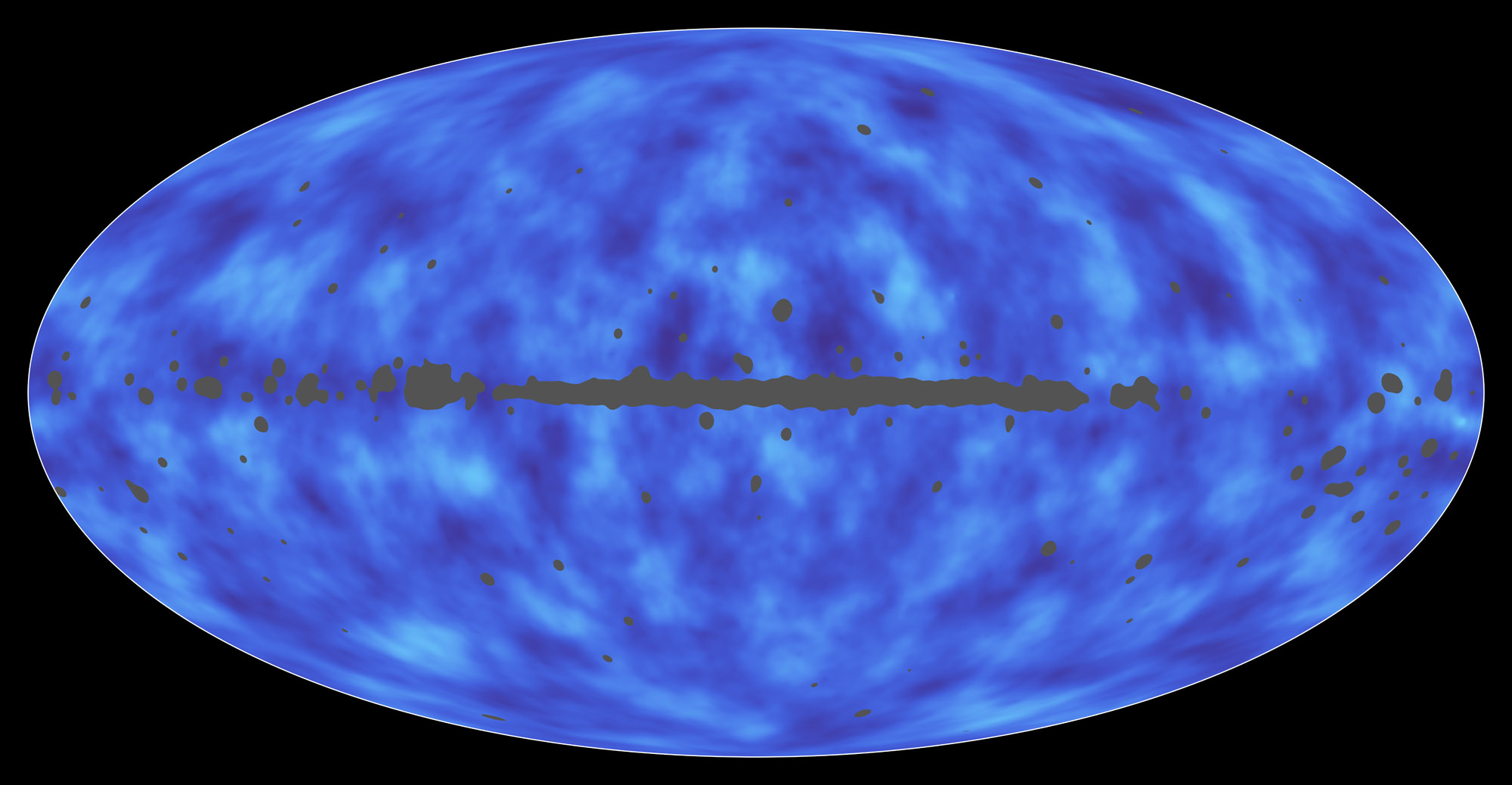

Milky Way Dust - Planck Map

This map of the Milky Way shows the distribution of interstellar dust across the galaxy as seen by the Planck space observatory, a mission by the European Space Agency. ESA and NASA unveiled the image on Feb. 5, 2015. Read the Full Story.

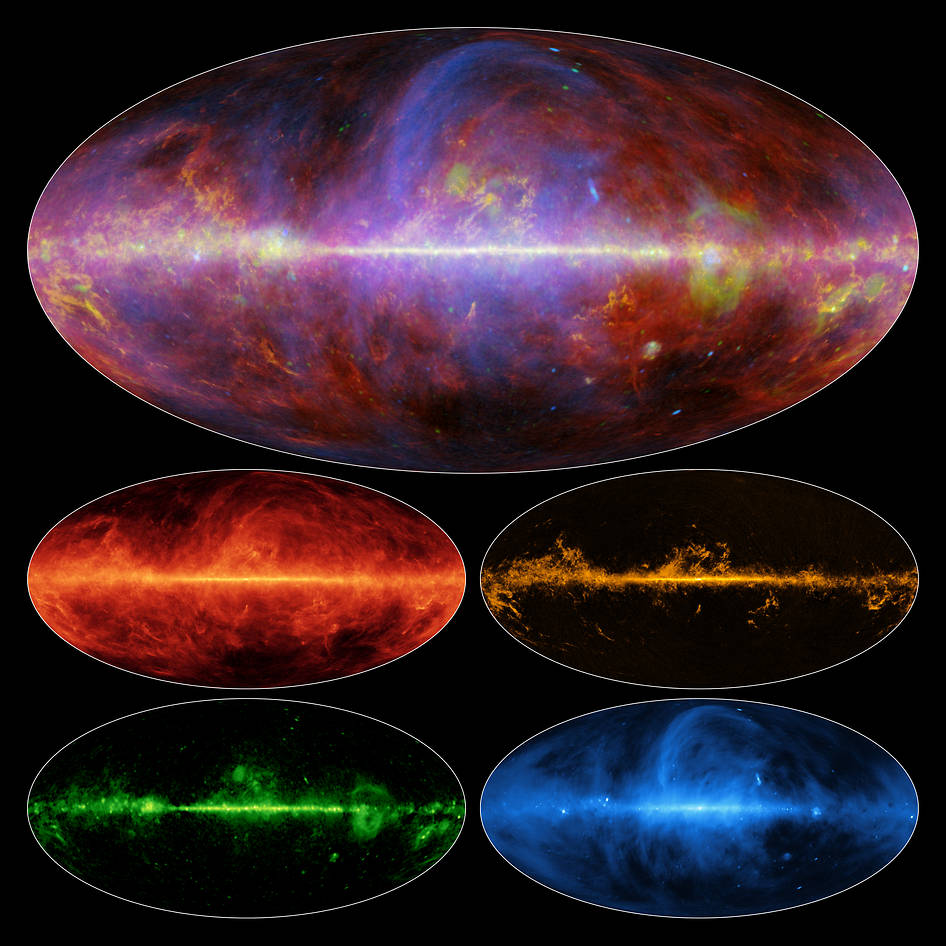

Article continues belowA View of the Milky Way in Microwaves

Each of the four bottom) show a specific subset of Planck observations that make up the combined view (top). Of the subsets, they show: Top left is dust, top right is gas, bottom right is light from charged particle interactions, and bottom right shows charged particles moving along the galaxy's magnetic field. Read the Full Story.

All the Matter in the Universe by Planck

All of the matter between Earth and the edge of the observable universe is shown in this image based on data from the European Space Agency's Planck space observatory. This map was released on Feb. 5, 2015. Read the Full Story.

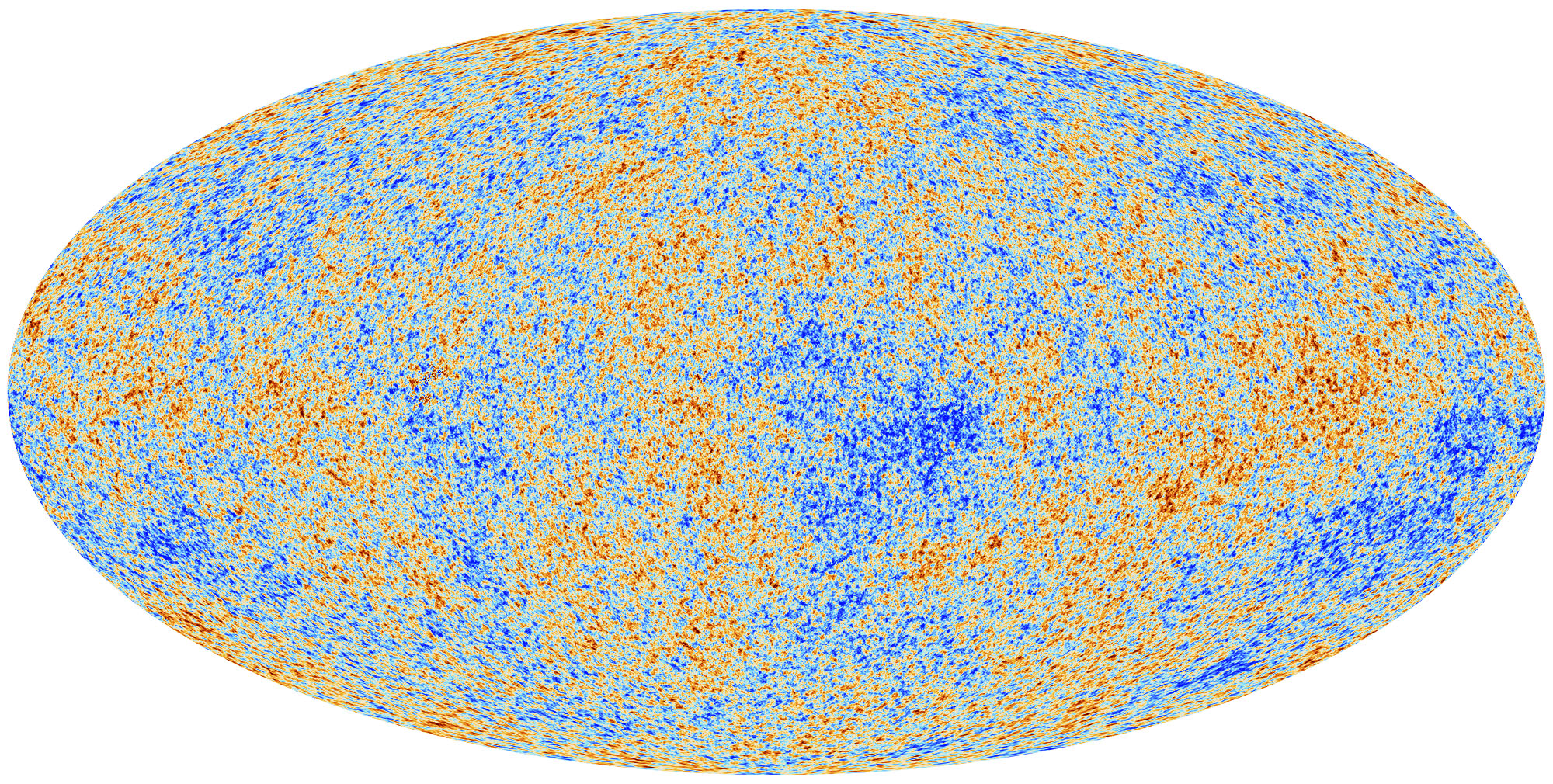

Planck's All-Sky Map: Cosmic Microwave Background

This image unveiled March 21, 2013, shows the cosmic microwave background (CMB) as observed by the European Space Agency's Planck space observatory. The CMB is a snapshot of the oldest light in our Universe, imprinted on the sky when the Universe was just 380 000 years old. It shows tiny temperature fluctuations that correspond to regions of slightly different densities, representing the seeds of all future structure: the stars and galaxies of today. [Full story.]

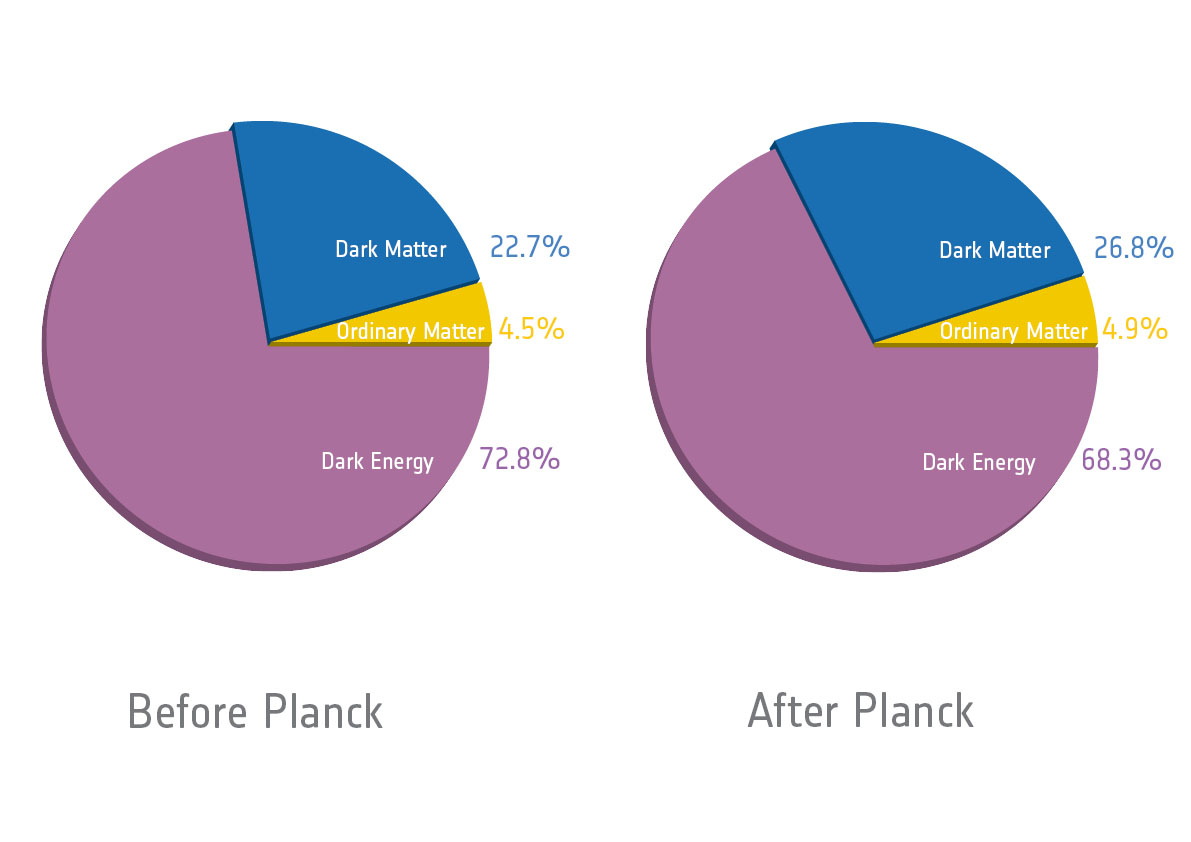

Planck's Ingredients of the Universe

This European Space Agency graphic depicts the most refined values yet of the Universe’s ingredients, based on the first all-sky map of the cosmic microwave background by the Planck space observatory unveiled on March 21, 2013. Normal matter that makes up stars and galaxies contributes 4.9 percent of the Universe's mass/energy inventory. Dark matter occupies 26.8 percent, while dark energy accounts for 68.3 percent. [Full story.]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

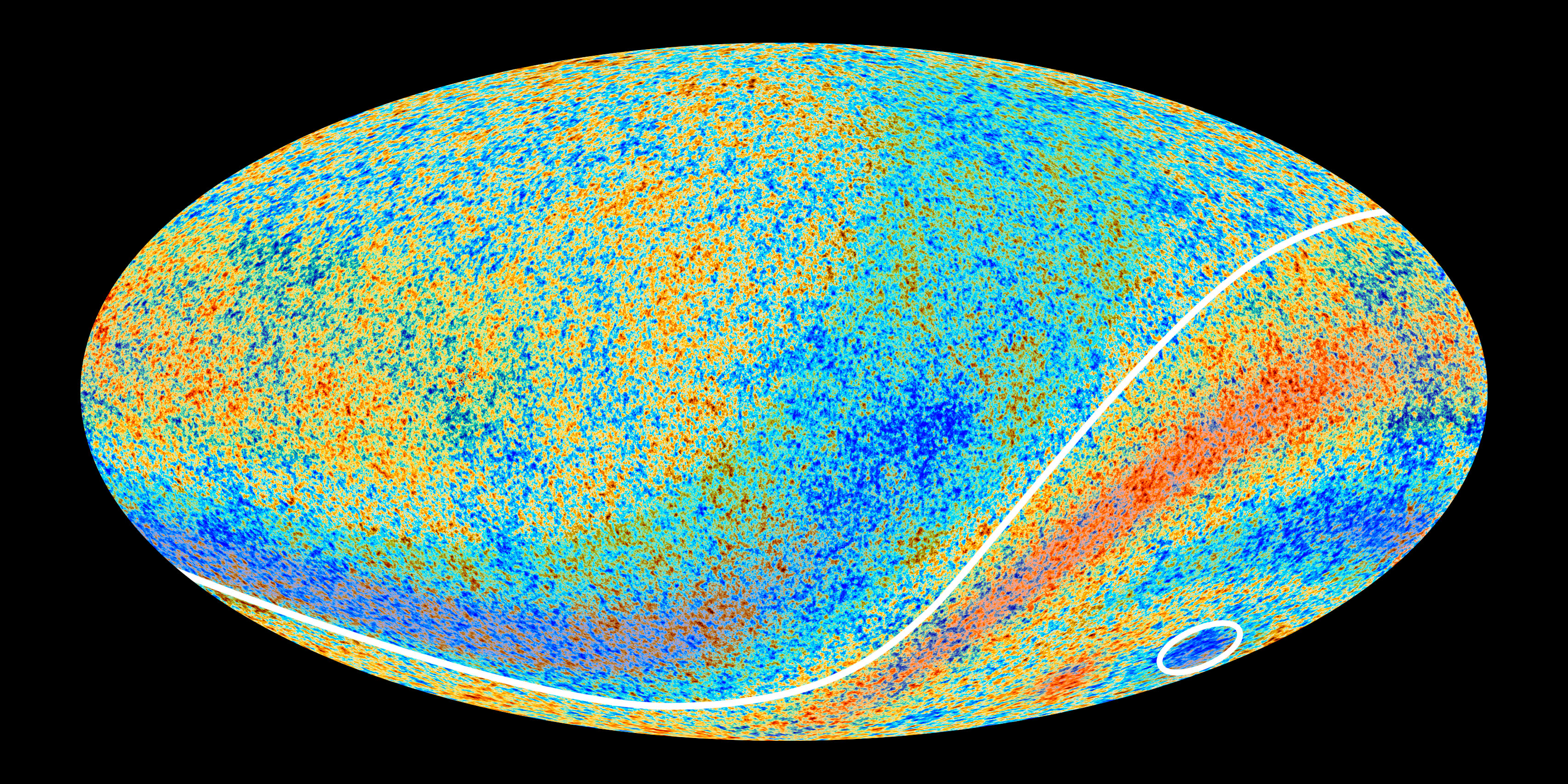

Planck's All-Sky Map: Cosmic Microwave Background Anomalies

Two Cosmic Microwave Background anomalies hinted at by the Planck observatory's predecessor, NASA's WMAP, are confirmed in new high-precision data revealed on March 21, 2013. In this image, the two anomalous regions have been enhanced with red and blue shading to make them more clearly visible. [Full story.]

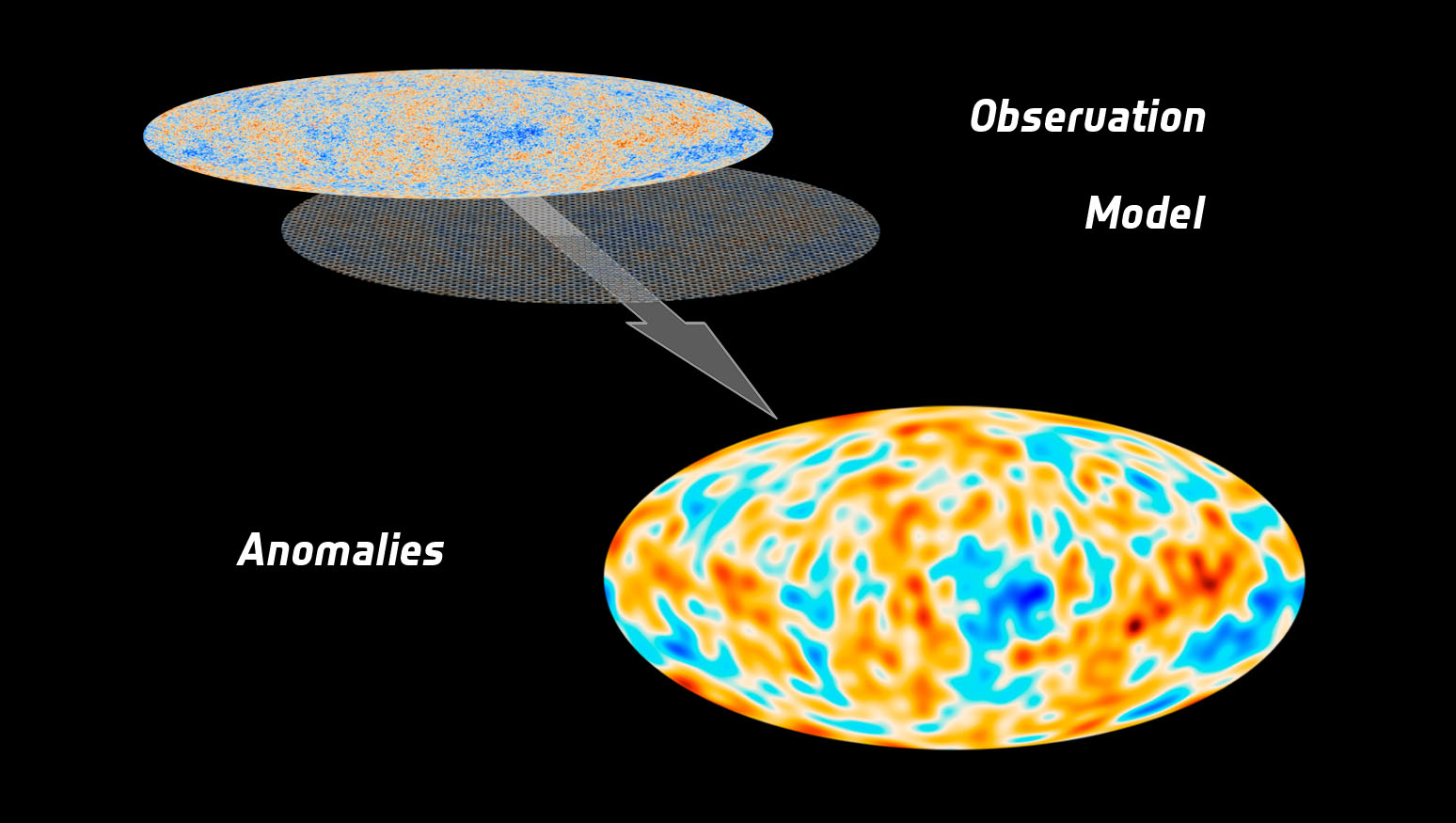

Planck's All-Sky Map vs. Standard Model

This European Space Agency graphic shows a map of the universe that depicts the anomalies seen when comparing the Planck space observatory's map of the universe's cosmic microwave background and the standard model of the cosmos. Image released March 21, 2013. [Full story.]

Planck All-Sky Image of Carbon Monoxide

This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck. Image released February 13, 2012.

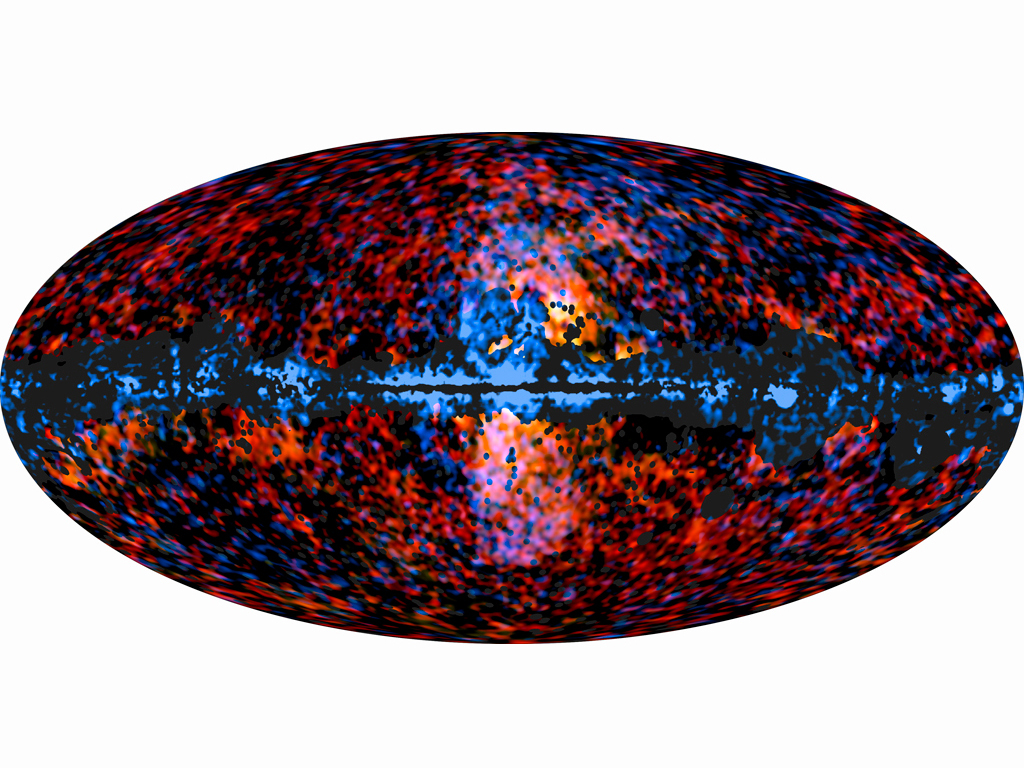

Galactic Haze Seen by Planck and Galactic 'Bubbles' Seen by Fermi

This all-sky image shows the distribution of the galactic haze seen by ESA's Planck mission at microwave frequencies superimposed over the high-energy sky, as seen by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Image released February 13, 2012.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.