So Much of the Arctic Is on Fire, You Can See It From Space

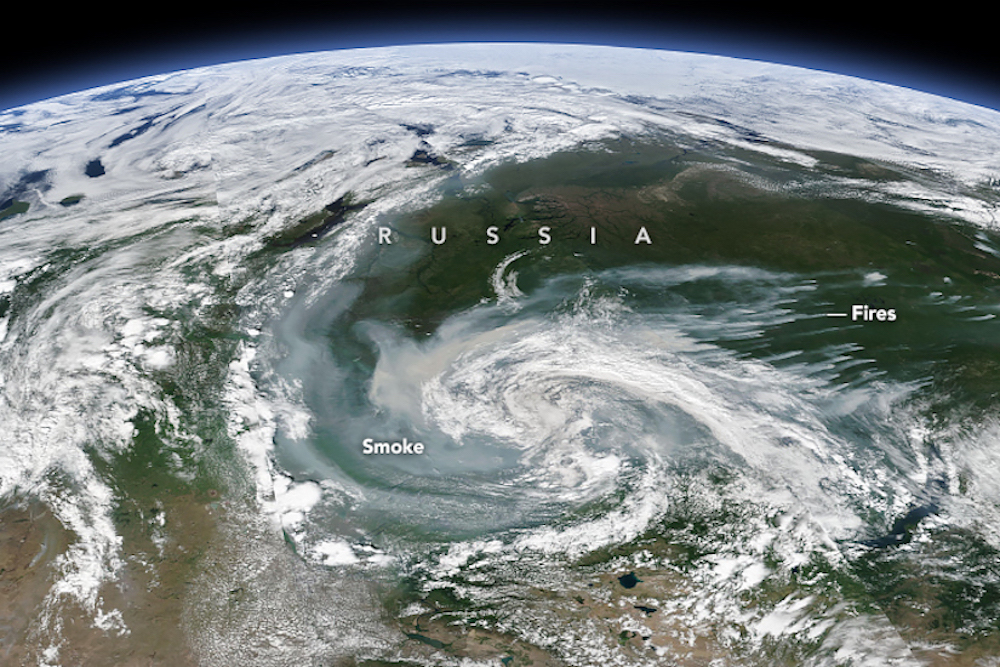

Wildfires burning large swaths of Russia are generating so much smoke, they're visible from space, new images from NASA's Earth Observatory reveal.

Since June, more than 100 wildfires have raged across the Arctic, which is especially dry and hot this summer. In Russia alone, wildfires are burning in 11 of the country's 49 regions, meaning that even in fire-free areas, people are choking on smoke that is blowing across the country.

The largest fires — blazes likely ignited by lightning — are located in the regions of Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk and Buryatia, according to the Earth Observatory. These conflagrations have burned 320 square miles (829 square kilometers), 150 square miles (388 square km) and 41 square miles (106 square km) in these regions, respectively, as of July 22.

Related: In Photos: Fossil Forest Unearthed in the Arctic

The above natural-color image, taken on July 21, shows plumes rising from fires on the right side of the photo. Winds carry the smoke toward the southwest, where it mixes with a storm system. The image was captured with the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP, a weather satellite operated by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Russian city of Krasnoyarsk is under a layer of haze, the Earth Observatory reported. And while Novosibirsk, Siberia's largest city, doesn't have any fires as of now, smoke carried there by the winds caused the city's air quality to plummet.

Wildfires are also burning in Greenland and parts of Alaska, following what was the hottest June in recorded history. It's common for fires to burn during the Arctic's summer months, but the number and extent this year are "unusual and unprecedented," Mark Parrington, a senior scientist at the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), a part of the European Union's Earth observation program, told CNN.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These fires are taking a toll on the atmosphere; they've released about 100 megatons of carbon dioxide from June 1 to July 21, which is roughly equivalent to the amount of carbon dioxide Belgium released in 2017, according to CAMS, CNN reported.

The Arctic is heating up faster than other parts of the world, making it easier for fires to thrive there. In Siberia, for example, the average June temperature this year is nearly 10 degrees Fahrenheit (5.5 degrees Celsius) hotter than the long-term average between 1981 and 2010, Claudia Volosciuk, a scientist with the World Meteorological Organization, told CNN.

Many of this summer's fires are burning farther north than usual, and some appear to be burning in peat soils, rather than in forests, Thomas Smith, an assistant professor of environmental geography at the London School of Economics, told USA Today. This is a dangerous situation, because whereas forests might typically burn for a few hours, peat soils can blaze for days or even months, Smith said.

Moreover, peat soils are known carbon reservoirs. As they burn, they release carbon, "which will further exacerbate greenhouse warming, leading to more fires," Smith said.

- In Photos: The Deadly Carr Fire Blazes Across Northern California

- In Photos: Devastating Wildfires in Northern California

- In Photos: The Vanishing Ice of Baffin Island

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is an editor at Live Science. She edits Life's Little Mysteries and reports on general science, including archaeology and animals. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and an advanced certificate in science writing from NYU.