What Really Killed the Dinosaurs? Asteroid and Volcanoes Might Share the Blame

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

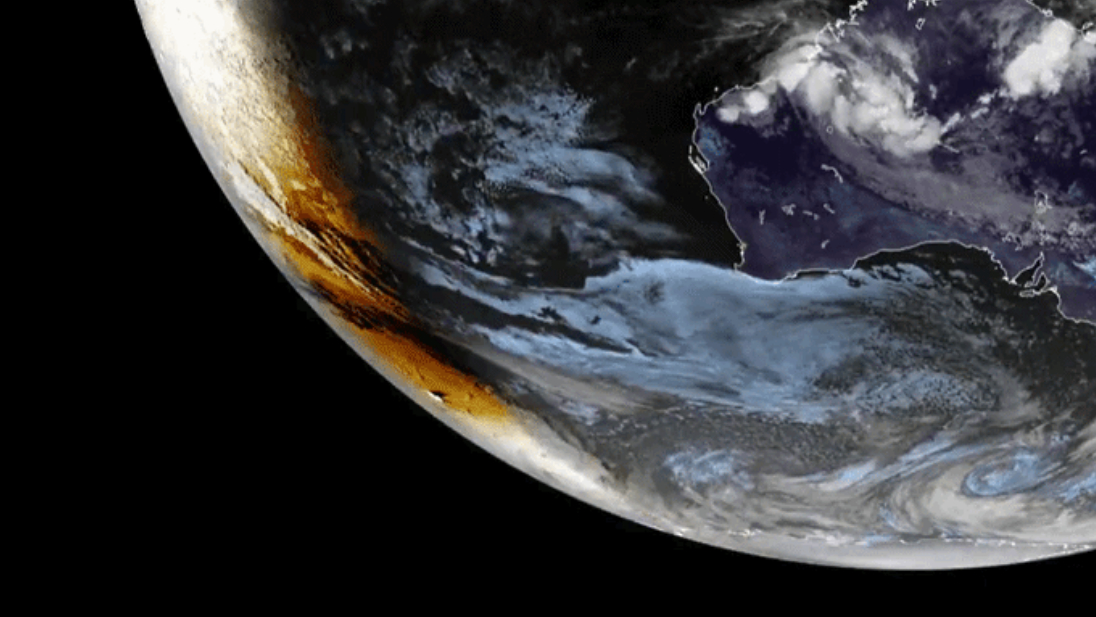

The asteroid or comet that smacked into Earth 66 million years ago might not be the only culprit behind the dinosaurs' demise.

Two new studies in the journal Science examine the possible connection between this impact (now visible as Chicxulub Crater in the region of Yucatan, Mexico), and huge volcanic eruptions in India, on the opposite side of the world. Researchers involved in the two separate studies say it's therefore unclear to what degree the impact, as opposed to the volcanoes, triggered the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs, as well as numerous other lifeforms.

In one of the papers, scientists uncovered the most precise dates yet for the Indian volcanic eruptions around the end of the Cretaceous period, when this mass extinction happened about 66 million years ago. During this million-year-long eruption, the volcanoes shot lava flows for hundreds of miles across India. This process created flood basalts, now called the Deccan Traps, that in some areas are nearly 1.25 miles (2 kilometers) thick. [Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space]

"I would say, with pretty high confidence, that the eruptions occurred within 50,000 years, and maybe 30,000 years, of the (asteroid) impact," that paper's senior author, Paul Renne, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement.

He added that given the study's margin of error, these eruptions occured at about the same time as the cosmic crash. "That is an important validation of the hypothesis that the impact renewed lava flows."

Explosive timing

That paper's authors also uncovered a surprise: Their new dating showed that about 75 percent of the lava created by the Deccan Traps erupted after the impact. If further research confirms it, that's a novel finding, as previous studies suggested that only 20 percent of the lava flowed after the asteroid or comet hit.

The scientists used a precise dating method called argon-argon dating to measure rocks formed around the same time as the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous and beginning of the Tertiary period. This area in the geological record is called the K-Pg boundary (formerly known as the K-T boundary).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the new paper, this team built on previous research they'd done pinpointing the date of the impact, which rocks collected in Montana suggested occurred 66,052,000 years ago, give or take 8,000 years.

They have also tackled the Deccan Traps dating conundrum before, in a 2015 investigation of Indian samples that showed that in at least one location, the eruptions happened within 50,000 years of the impact. Now, the scientists have obtained similar dates from a total of 19 rocks found at other locations in the Deccan Traps.

If most of the lava shot out after the impact, this has large implications for how the extinction played out. Here's what the standard narrative has been: If most of the Deccan Traps lava burst out before the impact, then the gases it generated could have caused global warming during the last 400,000 years of the Cretaceous. Observations show that global temperatures increased by about 14.4 degrees Fahrenheit (8 degrees Celsius), which would have forced species to evolve to live in these warmer temperatures. Then the disturbed ecosystem would have collapsed amid sudden global cooling after the impact kicked up dust (blocking the sun) or the volcanic gases cooled the climate.

The new scenario suggests climate change happened even before the eruptions peaked. If this happened, gases would have trickled out from underground magma chambers over a long period , similar to what is observed today at Mount Etna in Italy and Popocatepetl in Mexico. [In Pictures: The Giant Crater Beneath Greenland Explained]

"This changes our perspective on the role of the Deccan Traps in the K-Pg extinction," lead author Courtney Sprain, a former Berkeley doctoral student who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, said in the same statement. "Either the Deccan eruptions did not play a role — which we think unlikely — or a lot of climate-modifying gases were erupted during the lowest volume pulse of the eruptions."

There are many open questions with this research, though, particularly since volcanoes can produce both cooling and warming gases. And scientists have never been able to measure the output of a massive flood basalt eruption like the one at Deccan Traps in real time — the last such eruption finished about 15 million years ago, in the Pacific Northwest.)

The second new study also complicates matters, calculating slightly different date estimates for the Deccan Traps eruption. (The two groups analyzed different minerals; furthermore, one focused on the lava flows themselves, and the other on sediments found between lava flows.)

The research is described in two papers published today (Feb. 21) in the journal Science.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.