Here's What a Spacecraft Orbiting Uranus Could Learn

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

No spacecraft has gotten a close look at Uranus in more than three decades — but scientists know they want to go back, if they can design the right mission to do so.

That's why a team of early-career scientists and engineers spent part of their summer scoping out what $1 billion could buy them when it comes to the ice giant. They figured out that NASA could fit a Uranus mission into such a tight budget by jumping on a helpful planetary alignment and building on the legacy being created by the agency's Juno mission, which recently passed the halfway mark in its studies at Jupiter. With that approach, NASA could follow up on many of the mysteries that have puzzled scientists since Uranus' first robotic visitor flew by in 1986.

"I didn't realize that Voyager 2 had raised so many questions that we really, really need to answer, especially in light of all of these ice giant exoplanets that we've discovered," Stephanie Jarmak, a doctoral student at the University of Central Florida who acted as principal investigator for the mission design project, told Space.com. "We need to get more data, we need to send a spacecraft there."

Related: Photos of Uranus, the Tilted Giant Planet

So Jarmak and other attendees of a planetary summer seminar at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California designed just such a spacecraft — one that could launch in 2032 and arrive in 2045. After arriving, it would sneak into month-long orbits around the strange planet.

There, it would tackle some of scientists' most pressing questions about Uranus: why its highly tilted magnetic field is so weird, what its cloud tops hide that may be happening deeper within the planet and why the planet emits much less heat than its neighboring giant planets do.

"It's a really interesting target," Erin Leonard, a doctoral student in planetary geology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who acted as project manager for the design process, told Space.com. "We chose it a bit for the challenge also, to try to show that there is a lot that can be done within the New Frontiers cost cap." That NASA mission class — which has so far flown the spacecraft New Horizons to Pluto and beyond, Juno to Jupiter and OSIRIS-REx to an asteroid called Bennu — is capped at a $850 million budget, not including launch.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That meant that for such a long journey, weight was at a premium. "Even with a billion dollars, which sounds like a lot — even getting a brick to the outer solar system could cost as much as that," Jarmak said. So the team was careful to build upon the legacy of the Juno mission currently studying Jupiter to keep instrument costs down. "You can kind of think of this mission as being Juno but out at Uranus," she said.

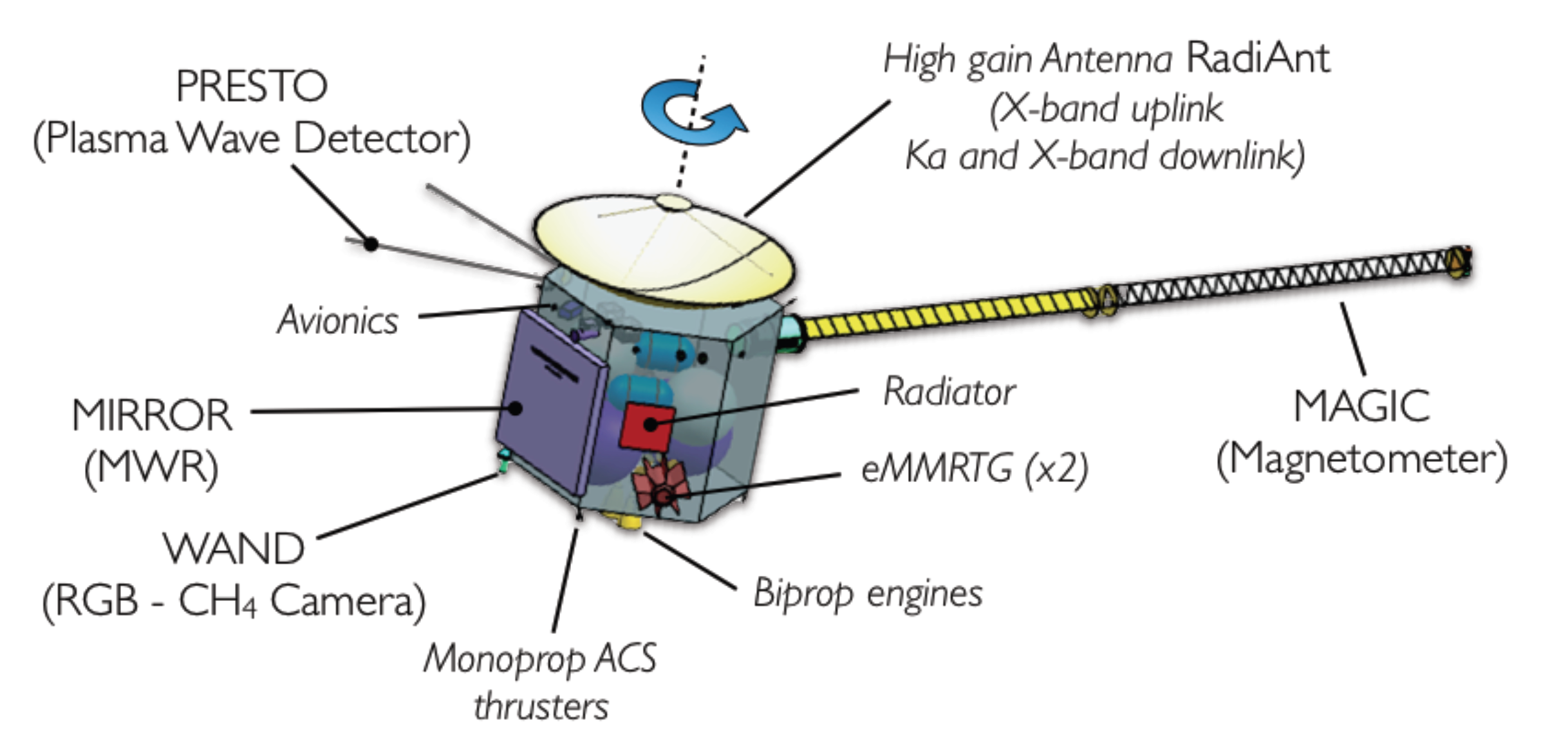

The approach meant that the team could arm the spacecraft with a handful of instruments, including a magnetometer, a methane detector and of course a camera, all adapted from similar models currently at Jupiter.

The team's second trick to staying in budget was to make use of a lucky alignment of the outer planets. "It's definitely a challenge, because you need either good gravity assists or good propellent, and that costs money," Leonard said. Jupiter, on the other hand, is just sitting there, cost free. So Jupiter it is.

There's just one catch: The alignment only works in the first half of the 2030s. That means the team's design, or any other spacecraft destined for the ice giant, will have the easiest time getting out to the right neighborhood of the solar system if it can swing past Jupiter by 2034. And to meet that kind of timeline, now is the time to plan what precisely should be on board.

And although neither Jarmak nor Leonard specializes in Uranus itself, both are excited by the idea that a mission like theirs could one day visit the ice giant, which resembles the most common class of exoplanets that scientists are finding so far.

"Ice giants are great, Uranus is awesome," Leonard said. "I think we can really learn a lot from Uranus."

- Uranus May Have Odd, Strobe-Like Magnetic Field

- Why Is Uranus on Its Side? Incredible Simulations Could Solve the Mystery.

- How Did Uranus Form?

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.