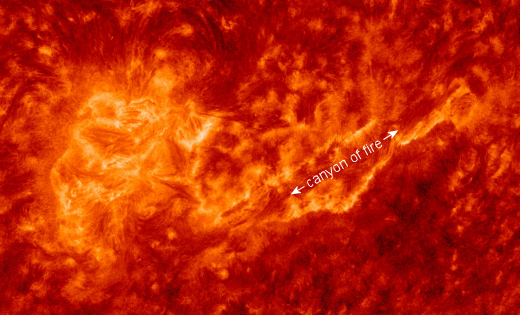

Sun spits filaments out from 'canyon of fire' as aurora forecast remains strong

The "canyon of fire" is at least 12,400 miles (20,000 kilometers) deep and 10 times as long.

Filaments of plasma escaped from a fiery canyon that opened on the sun's surface on Sunday (April 3) releasing powerful streams of magnetized solar wind that might bring more auroras to Earth later this week.

According to Space Weather, the "canyon of fire" is at least 12,400 miles (20,000 kilometers) deep and 10 times as long.

The U.K. weather forecaster Met Office confirmed that two "filament eruptions" occurred in the south-central part of the sun. Satellites in the extreme ultraviolet part of the electromagnetic spectrum and ground telescopes equipped to observe in the warmth-carrying infrared wavelengths were both able to see the eruptions.

The first filament blasted from the sun on Sunday (April 3) at about 11 a.m. EDT (1500 GMT); the second followed on Monday (April 4) at about 5 p.m. EDT (2100 GMT).

Related: A hyperactive sunspot just hurled a huge X-class solar flare into space

Both eruptions were accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs), expulsions of charged plasma from the sun's upper atmosphere or the corona, the Met office said in a statement. When a CME hits Earth, it can wreak havoc with the planet's magnetic field, causing a geomagnetic storm.

Powerful geomagnetic storms can disrupt satellite links and damage electronics in orbit. In some cases, these storms can even disturb power networks on the ground. On the upside, geomagnetic storms often treat skywatchers on Earth to mesmerizing aurora displays.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The CME related to Sunday's eruption will reach Earth at about 10 a.m. EDT (1200 GMT) on Wednesday (April 6) and will likely trigger only a mild geomagnetic storm, level G1 or G2 on a five-point scale, Met Office said. Space weather forecasters don't know yet whether the CME produced by the Monday eruption will hit the planet, the Met Office added.

Either way, polar lights are likely to get a boost in the coming days, which could make them observable farther away from the polar regions than usual. Since Earth's magnetic field is the weakest above the poles, magnetized particles from CMEs penetrate deeper into Earth's atmosphere in those regions. The interaction between the solar particles and those in the atmosphere then causes the colorful glows.

According to the Met Office, Earth's geomagnetic environment will likely get quieter in the coming days since the overactive sunspot that has been responsible for a recent burst of activity has rotated away from the Earth-facing position.

Overall, solar activity is currently relatively subdued as the sun has only recently started waking up from a prolonged solar minimum, a phase in its 11-year cycle of activity with barely any sunspots. Solar activity will likely pick-up over the coming years; scientists expect it to peak around 2025.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.