We May Finally Know How the Universe's Heavy Elements Formed

Scientists detected strontium in the aftermath of a dead-star collision.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

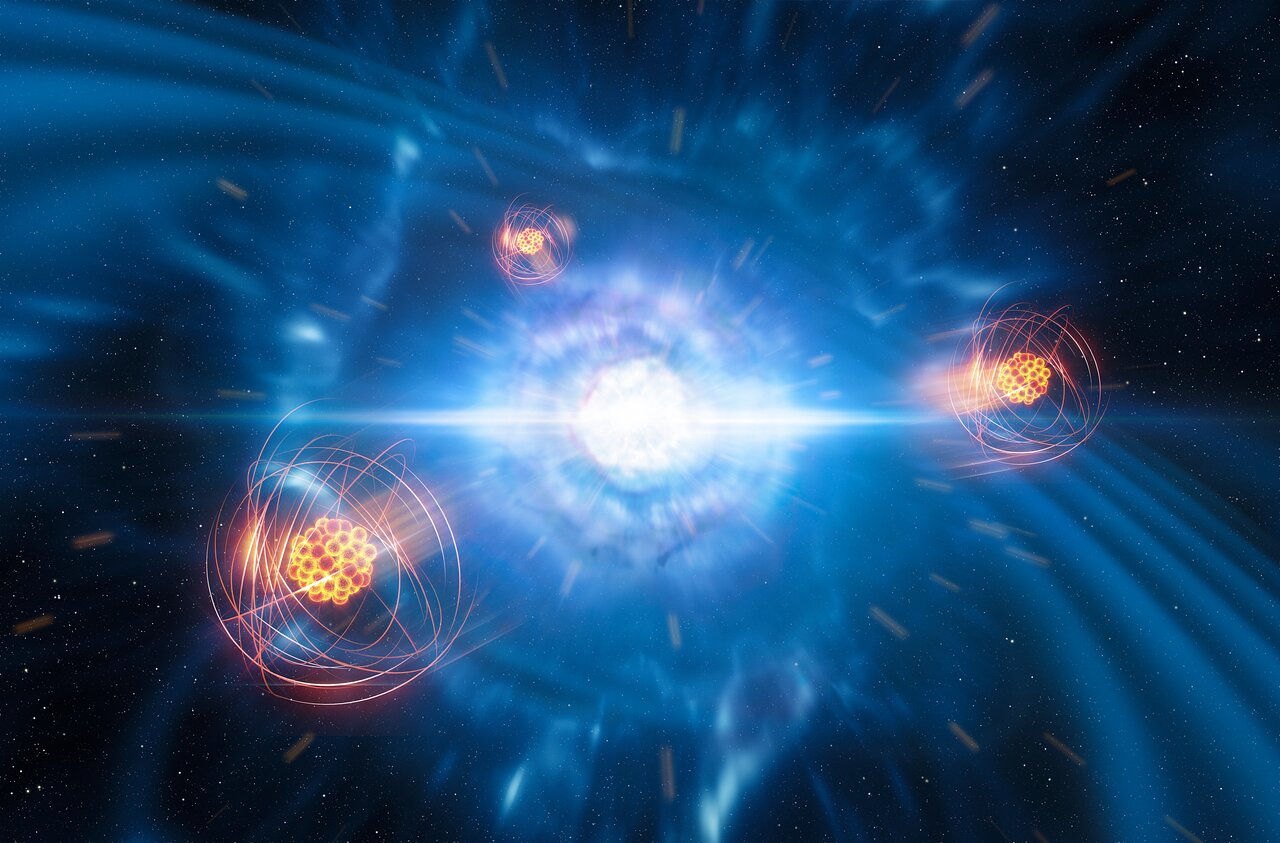

For the first time, scientists have detected a newly born heavy element in space, forged in the aftermath of a collision between a pair of dead stars known as neutron stars.

The findings shed light on how the universe's heaviest elements are created, providing a missing piece of the puzzle of chemical element formation, researchers said in a new study describing the findings.

The results also confirmed that "neutron stars have neutrons in them," study lead author Darach Watson, an astrophysicist at the University of Copenhagen's Niels Bohr Institute, told Space.com. "That sounds really dumb, but it's something we haven't known for sure. Now, everything we've found points to elements that formed only in the presence of lots of neutrons."

Related: First Glimpse of Colliding Neutron Stars Yields Stunning Pics

The early universe

The universe's three lightest elements — hydrogen, helium and lithium — were created in the earliest moments of the cosmos, just after the Big Bang. Most of the quantities of elements heavier than lithium, up to iron on the periodic table, were forged billions of years later, in the cores of stars.

But how elements heavier than iron, such as gold and uranium, were created has long been uncertain. Previous research suggested a key clue: For atoms to grow to massive sizes, they needed to quickly absorb neutrons. Such rapid neutron capture, known as the "r-process" for short, only happens in nature in extreme environments where atoms are bombarded by large numbers of neutrons.

Prior work suggested that a likely source of r-process elements could be the catastrophic aftermath of mergers between neutron stars, which are the superdense cores of stars left behind after cataclysmic, explosive star deaths known as supernovas. The name neutron star comes from how their gravitational pull is strong enough to crush protons and electrons together to form neutrons.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Witnessing a neutron star merger

In 2017, astronomers witnessed, for the first time, a pair of neutron stars merging. The scientists made the discovery by detecting gravitational waves, or ripples in the fabric of space-time, which radiated from a collision that happened about 130 million light-years from Earth. Following the discovery of this merger, dubbed GW170817, scientists continued to make telescopic observations from Earth.

"This explosion was traveling like 30% of the speed of light, so it went from about 100 kilometers [60 miles] in size to the solar system's size in a day," Watson said.

Watson and his colleagues suspected that, if heavier elements did form during GW170817, signatures of those elements might be detected in the explosive aftermath of the merger, known as a kilonova. They focused on the wavelengths of light, or spectral lines, that, through spectroscopy, scientists have linked to specific elements.

Prior work suggested the presence of heavy elements within the kilonova, but until now, astronomers could not pinpoint individual elements in the aftermath. This is because "heavier elements can produce blends of tens of millions of spectral lines," Watson said. "We could never tell one element from another."

However, by reanalyzing data from the 2017 merger, Watson and his colleagues have now identified the signature of the heavy element strontium within the fireball. On Earth, strontium is found naturally in soil and is concentrated in certain minerals. Strontium compounds even help to give fireworks a brilliant red color.

The strontium key

The key behind this research team's success was strontium's atomic structure, which is relatively simple for such a heavy element. Because of its structure, the electrically charged version of strontium produces two powerful spectral lines in blue and infrared light.

"The fact that we can detect any element in this radioactive explosion is quite surprising," Watson said.

This discovery was surprising because, while strontium is a heavy element, it is also one of the lightest r-process elements. In previous research, scientists expected to find "heavier heavy elements," or heavier r-process elements, "when looking at a kilonova," Watson said.

The key behind this surprising find might be linked with ghostly particles known as neutrinos, which normally pass through conventional matter but can occasionally collide with protons or neutrons.

"In order to create a relatively light heavy element like strontium, you need to destroy some neutrons first — you need to bombard them with neutrinos, enough to make them decay more quickly into protons and electrons," Watson said. "This tells us a bit more about what's happening within neutron stars, and what occurs during such mergers."

Now, it might be challenging for scientists to detect other heavy elements from neutron star collisions, as there is little quality data on the atomic structures of heavy elements, given their complex nature, Watson said. Still, within the next few years, he and his colleagues hope to collect data that might help them detect other heavy elements within kilonovas, he said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Oct. 24 issue of the journal Nature.

- Cosmic Cocoon Spawned by Powerful Neutron Star Crash

- Ancient Neutron-Star Crash Made Enough Gold and Uranium to Fill Oceans

- Closer Look at Neutron Star Crash Demystifies Huge Stellar Explosions

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us