SpaceX's 1st Starship and Super Heavy launch: How it will work

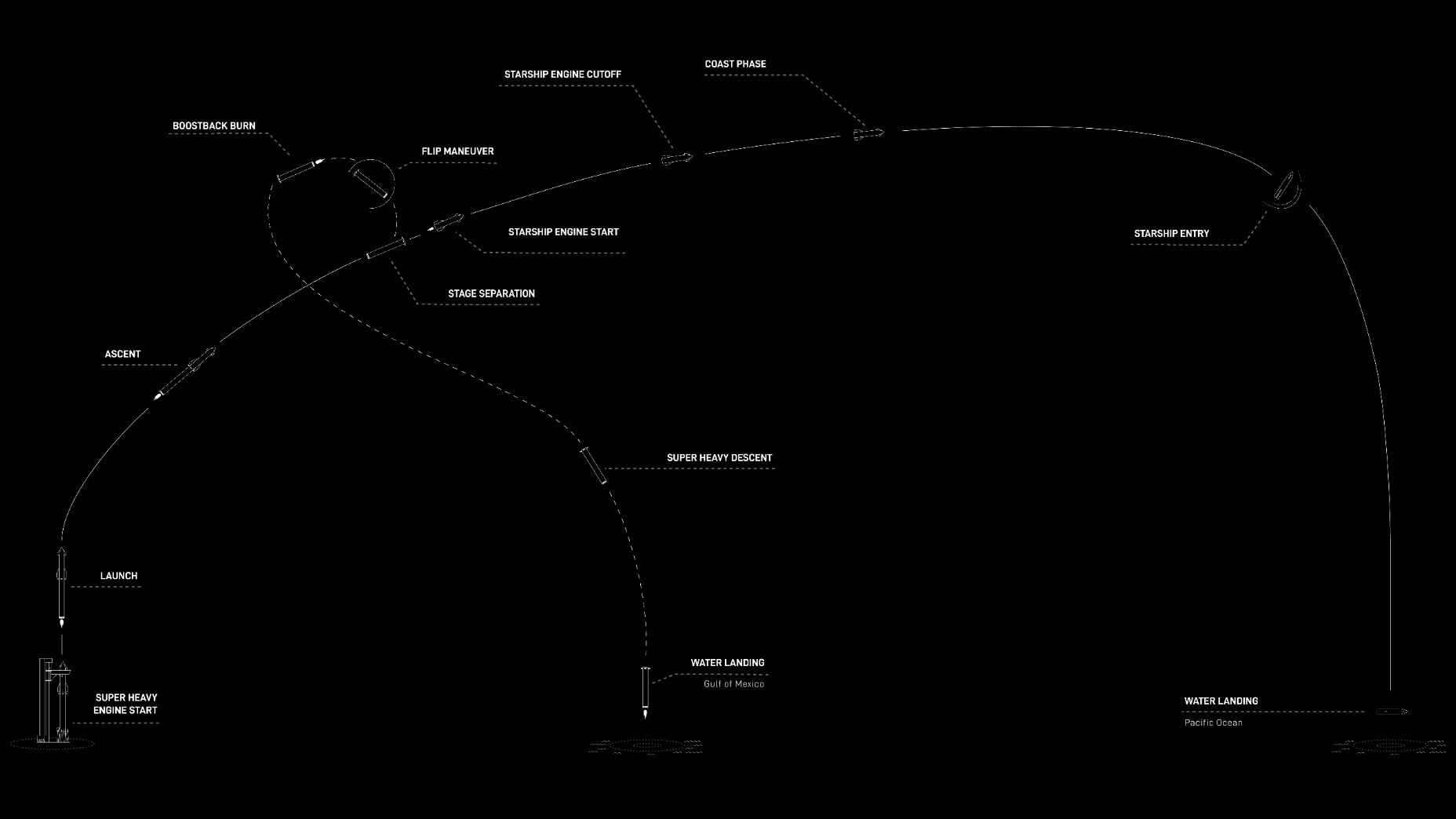

The test flight will launch from South Texas, head over the Gulf of Mexico and ultimately splash down near Hawaii.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

SpaceX is gearing up for a huge milestone: the first near-orbital-velocity launch of its combined Super Heavy booster and Starship upper stage.

The Starship deep-space rocket system is scheduled to launch from SpaceX's Starbase facility near Boca Chica, Texas, on Thursday (April 20) at 9:28 a.m. EDT (1328 GMT) during a 62-minute window that is expected to close at 10:30 a.m. EDT (1430 GMT). SpaceX's webcast will begin 45 minutes before launch at 8:45 a.m. EDT (1215 GMT)

The gigantic 394-foot-tall (120 meters), two-stage Starship was stacked on the orbital launch mount at Starbase on April 5, ready for testing ahead of launch. A launch attempt on April 17 was called off due to a fueling issue.

Related: How to watch SpaceX's its 1st Starship orbital launch

You can have a Starship of your own with this desktop rocket model. Standing at 12.5 inches (32 cm), this is a 1:375 ratio. See our roundup of awesome Starship gear.

Starship consists of a huge first-stage booster, called Super Heavy, and an upper-stage spacecraft known as Starship. The test flight will, specifically, use the prototypes Ship 24 and Booster 7.

Starship and its test flights have been among the most captivating developments in the space sector, and the first orbital mission has been long anticipated. The test launch will, however, be another step on a long road toward the launcher becoming fully operational.

When it does launch, the entire flight will take around 90 minutes, starting at Starbase, flying east over the Gulf of Mexico and between the Straits of Florida, and finishing off near Hawaii.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Both Super Heavy and Starship are designed to be fully reusable, but this will be the only flight for Booster 7 and Ship 24; both vehicles will splash down in the ocean rather than make vertical, powered landings on terra firma or a "drone ship," as the first stages of SpaceX's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets commonly do.

Booster 7's 33 Raptor methane-liquid oxygen engines are planned to shut down 169 seconds into the flight and separate from Ship 24 three seconds later, according to SpaceX's mission description. Booster 7 will restart a select few of its engines to bring it back toward Texas, ultimately splashing down approximately 20 miles (32 kilometers) off the coast in the Gulf of Mexico about eight minutes after launch.

The Starship upper stage's six Raptor engines, meanwhile, will start up after 177 seconds, or just under three minutes into the flight, continuing the vehicle's journey eastward. Those engines will burn for about 6.5 minutes, shutting down 560 seconds into the flight.

Ship 24 will not complete a full orbit of Earth, but it will reach close to what is being termed orbital velocity — for low Earth orbit, about 17,500 mph (28,160 kph) — at an altitude of approximately 150 miles, if all goes according to plan. Officials with the Federal Aviation Administration have dubbed it a near-orbital velocity flight.

Starship will then put itself through a testing, high-velocity reentry into Earth's atmosphere. If all goes well, it will splash down approximately 62 miles (100 km) off the northwest coast of Kauai, part of the Hawaiian archipelago.

This splashdown is scheduled to occur 90 minutes after liftoff from Boca Chica. The test flight aims to provide lots of valuable information for SpaceX as it looks to get Starship fully operational.

"SpaceX intends to collect as much data as possible during flight to quantify entry dynamics and better understand what the vehicle experiences in a flight regime that is extremely difficult to accurately predict or replicate computationally," according to a document about the test flight that SpaceX submitted to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2021.

"This data will anchor any changes in vehicle design or CONOPs [concept of operations] after the first flight and build better models for us to use in our internal simulations."

In another 2021 FCC filing, SpaceX states that both the booster and Starship spacecraft will sport Starlink satellite terminals in order to demonstrate high-data-rate communications during in-flight operations.

"SpaceX's satellite constellation can provide unprecedented volumes of telemetry and enable communications during atmospheric entry when ionized plasma around the spacecraft inhibits conventional telemetry frequencies. These tests will demonstrate its ability to improve the efficiency and safety of future orbital spaceflight missions," the filing reads.

SpaceX has been churning out numerous prototypes of its Starship elements, with improvements to its structures, systems and software being considered and implemented after each test or flight. Some of its major milestones have been followed instantly by explosive conclusions.

This first near-orbital-velocity flight is the most challenging and significant step so far, and it will provide a number of lessons regardless of the outcome.

SpaceX's long-term vision is to have Starship transporting crew and cargo to the moon and Mars, with its reusability also greatly reducing the cost of launch.

Editor's note: This story was corrected to reflect that SpaceX's Starship will not reach orbital velocity during its first test flight. The FAA has classified its test flight as a near-orbital velocity flight.

This story was updated on April 18 at 9 a.m. EDT to reflect the new launch time.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.