Satellites watch record-breaking wildfires burn across Alaska

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

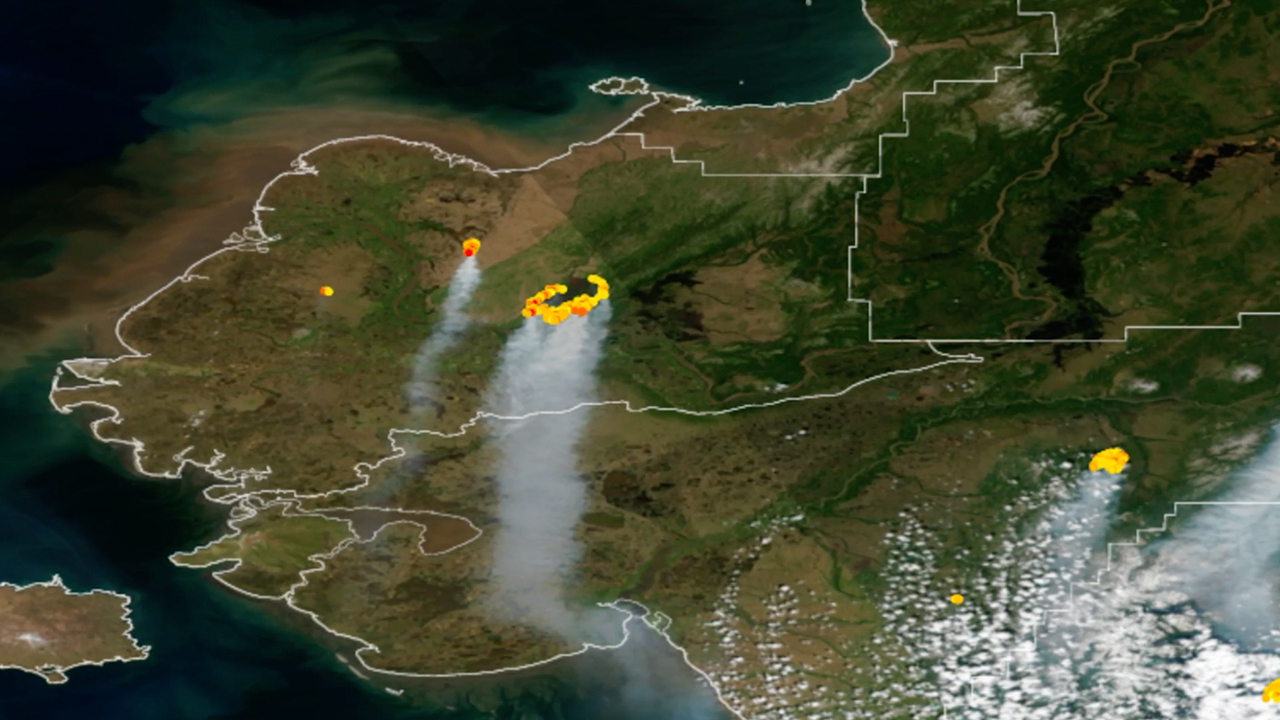

A hot, dry start to summer has sparked a record number of wildfires in southern Alaska, and weather satellites are tracking the development of the blazes from space.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) geostationary satellites have captured striking images of the fires burning across south-central and southwestern Alaska since early June. Lightning strikes from thunderstorms are sparking these early-season wildfires, which are then feeding on dry vegetation from a mild winter, according to a statement from NOAA.

"This year has been an unusually active fire season in the region, with abnormally warm and dry conditions that led to more than 300 wildfires igniting in recent weeks," NOAA officials wrote.

Related: Astronaut watches California wildfires spewing smoke from space (photos)

As of Thursday (June 30), 157 active fires were burning across Alaska. In just one month, wildfires in the state have burned more than 1.6 million acres — a threshold that Alaska has not reached this early in the fire season in decades.

The blazes include the East Fork Fire in the western part of the state near the Yukon Delta is one of the largest tundra fires on record and has burned more than 250,000 acres since May 31. Meanwhile, the Lime Complex Fire in the southwestern region of the state is even larger, spreading across more than 600,000 acres.

The smoke and debris from the fires have compromised air quality, leading the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation to issue warnings for numerous regions in the state, according to the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NOAA satellites offer crucial insight on the wildfires and how they spread. In particular, scientists use data from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument on the Joint Polar Satellite System's NOAA-20 and Suomi NPP satellites to detect and track wildfires, especially in remote regions.

"The high spatial resolution from VIIRS allows the instrument to detect smaller and lower-temperature fires," NOAA officials wrote. "VIIRS also provides nighttime fire detection capabilities through its Day-Night Band, which can measure low-intensity visible light emitted by small and fledgling fires."

The NOAA's GOES-16 and GOES-17 satellites also help early detection in remote areas, identifying wildfires from orbit before people spot them on the ground. These satellites are equipped with infrared image technology, which allows them to detect hot spots in real-time and pinpoint the intensity of a fire. The infrared data also allows scientists to track the subsequent smoke-infused thunderstorms, or pyrocumulonimbus clouds, that can lead to severe weather.

"The benefits provided by the latest generation of NOAA satellites aren't just seen during a fire but are important in monitoring the entire life cycle of a fire disaster," NOAA officials wrote. "Data from the satellites are helping forecasters monitor drought conditions, locate hot spots, detect changes in a fire's behavior, predict a fire's motion, monitor smoke and air quality, and monitor the post-fire landscape like never before."

The NOAA's weather prediction system, called the High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR)-Smoke model, provides a 48-hour forecast of both surface and high-altitude smoke. This model, paired with data from NOAA's satellites, provide detailed measurements of the amount of smoke produced, the plume height and the direction the smoke is expected to move, which fire crews, first responders and air traffic controllers can use to track and react to the wildfires.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.