'Ring of fire' eclipse 2021: When, where and how to see the annular solar eclipse on June 10

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Editor's note: The "ring of fire" solar eclipse of 2021 has ended. See video and photos of the eclipse here in our full story. And here's our photo gallery of the eclipse.

Northern and eastern sections of North America will experience a weird and dramatic event next Thursday (June 10).

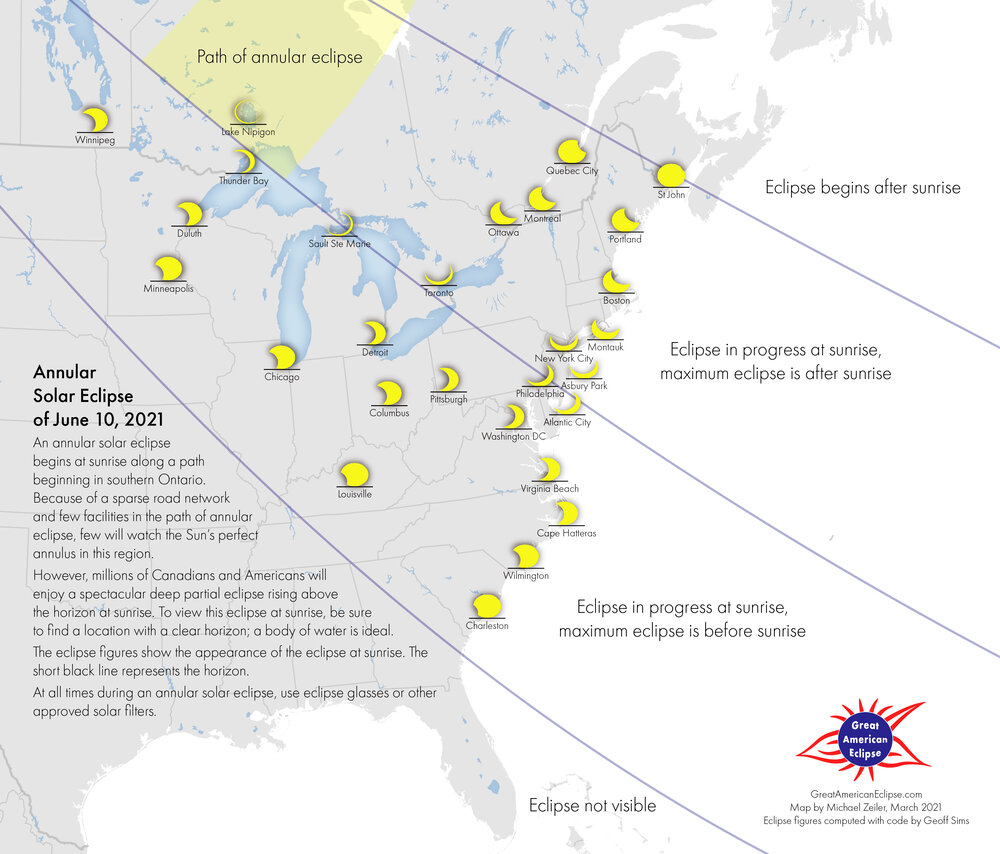

A partial solar eclipse will be visible, and for many, it will more or less coincide with sunrise. Only for places north of a line running roughly from Churchill, Manitoba, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, will the entire eclipse be visible from start to finish after the sun rises. Elsewhere, depending on where you are, if your sky is clear toward the east-northeast, the rising sun will appear slightly dented, deeply crescent shaped, or even ring shaped.

Across a swath of central and eastern Canada — encompassing the provinces of western and northern Ontario and a slice of northwest Quebec, as well as eastern Nunavut, Canada's newest territory — viewers living within a path averaging about 390 miles (630 kilometers) wide will have a front-row seat to witness the rare and exciting spectacle of an annular or "ring of fire" solar eclipse.

Related: Visibility maps to see the annular solar eclipse of 2021

Because the moon will be just 57 hours past apogee, its farthest point from Earth during its orbit, it will appear somewhat smaller than usual — smaller than the apparent disk of the sun. It is for this reason that viewers in the shadow's center will get an annular rather than a total eclipse: the sun will become a brilliant ring (or annulus) of light encircling the moon's dark silhouette for several minutes.

Related: The most amazing photos of the 2017 total solar eclipse

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Where to see the 'ring of fire' solar eclipse of 2021

If you snap a photo of the 2021 annular solar eclipse let us know! You can send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

The path of annularity begins along the northernmost shoreline of Lake Superior, where lucky skywatchers with clear skies will see the rising sun morph from an upturned horseshoe with pointed tips into a "ring of fire" for about 3.5 minutes. Because the eclipse track passes mostly over the boreal forests of the Canadian Shield and Canadian Arctic tundra, probably the best places to see the eclipse will be in Northwest Ontario. Locations within the path include the communities of Marathon, Longlac and Geraldton, where the annular phase will commence just a few scant minutes after sunup.

The ring will shine with only one-tenth of the sun's normal total light, but this is less of a change than it sounds, since the eye adapts readily to changing light levels. The illumination will be no darker than on a bright overcast day. The quality of the light, however, may become unearthly. A clear sky should turn deep blue and the landscape an odd silvery hue.

Near the point of greatest eclipse over the polar region, the annular phase will last up to 3 minutes and 51 seconds if you are on the centerline. Nearer the edge of the path, the duration will be shorter, and the ring will look lopsided, with one side wider than the other.

Sadly, Americans who would like to position themselves within the path of annularity will not be able to do so, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. The borders between the United States and Canada have been closed for over a year, and they will remain closed until sometime after this eclipse has passed into history. But even if you're not positioned within the track of the ring phase, you shouldn't get too envious, as the partial eclipse is definitely a calendar marker most everywhere from where it will be visible.

Unfortunately, for those living to the south and west of a line running roughly from Edmonton, Alberta, to Des Moines, Iowa, down through Savannah, Georgia, the eclipse will end before sunrise, so most of the southern and western United States will miss out on seeing the solar show. Places just to the north of this line will see a small scallop or bite taken out of the bottom part of the sun as it rises. The farther to the north and east one goes, the larger the bite will appear as the sun emerges into view.

Related: Total solar eclipse 2024: Here's what you need to know

What will the 'ring of fire' eclipse look like?

Early on the morning of June 10, an eerie and most unusual sight awaits residents who live around the northern Great Lakes, eastward to across New York state, New England and southeast Canada. At least four-fifths of the sun's diameter will be eclipsed by the dark disk of the moon as the sun ascends above the east-northeast horizon.

Hundreds or thousands of years ago, many people would probably have been terrified by the sun's misshapen appearance in such a partial eclipse, thinking that the sun was diseased, under attack or foretelling woe to its watchers. However, in today's high-tech world, this type of sun blockage has little scientific value and can in no way match the excitement generated by a total solar eclipse.

Nevertheless, timings of when the moon appears to first move onto or off the disk of the sun (called first and last "contact") are useful. An Arctic explorer in the late 19th century might have carefully timed these events for the chance of getting a reasonably good fix on his or her longitude, after months of rugged dogsledding when a chronometer could no longer be trusted to provide Greenwich time. By observing the annular eclipse of Aug. 5, 1766, the famous navigator Capt. James Cook determined the longitude of an island off the coast of Newfoundland. Cook's calculation differs from the modern value by only 22 arc seconds.

In a partial eclipse, the indentation appears to swing around the sun's limb, moving roughly from west to east (right to left). During the June 10 eclipse, it will be largest when positioned to the northeast (upper left) of the sun's center. As it continues moving eastward (toward the left), it will shrink and finally depart, leaving the sun whole again.

Viewing times for the 'ring of fire' solar eclipse

The table provided below tells when the sun rises, when the eclipse reaches maximum and when it ends at various cities, which are listed approximately from west to east. Daylight saving times are given for each location. When interpolating for a site between two cities, convert the times to the same time zone if they are not already. If the greatest phase of the eclipse occurs prior to sunrise, then the maximum eclipse — the largest amount of the sun that will be covered — will coincide with sunrise and is denoted with an asterisk (*). Also given is the magnitude of the eclipse, which is the percentage of the sun's diameter covered by the moon at maximum.

Since this upcoming eclipse is a low-sky event in most places, it may yield some interesting photographs. A telephoto lens might show the sun's disk, with a large section of it removed, hanging over or rising behind a picturesque landscape or seashore.

| Location | Time zone | Sunrise | Max. eclipse | Magnitude | Eclipse ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago, IL | CDT | 5:18 a.m. | 5:18 a.m.* | 35.6% | 5:39 a.m. |

| Minneapolis, MN | CDT | 5:29 a.m. | 5:29 a.m.* | 30.4% | 5:46 a.m. |

| New York, NY | EDT | 5:24 a.m. | 5:32 a.m. | 79.7% | 6:30 a.m. |

| Boston, MA | EDT | 5:07 a.m. | 5:33 a.m. | 80.0% | 6:32 a.m. |

| Montreal, PQ | EDT | 5:05 a.m. | 5:39 a.m. | 85.0% | 6:38 a.m. |

| Quebec City, PQ | EDT | 4:51 a.m. | 5:39 a.m. | 85.0% | 6:40 a.m. |

| Toronto, ON | EDT | 5:36 a.m. | 5:40 a.m. | 86.2% | 6:38 a.m. |

| Washington, DC | EDT | 5:45 a.m. | 5:45 a.m.* | 68.6% | 6:29 a.m. |

| Cleveland, OH | EDT | 5:55 a.m. | 5:55 a.m.* | 66.6% | 6:35 a.m. |

| Charleston, SC | EDT | 6:14 a.m. | 6:14 a.m.* | 11.7% | 6:21 a.m. |

| Indianapolis, IN | EDT | 6:19 a.m. | 6:19 a.m.* | 29.4% | 6:35 a.m. |

| Knoxville, TN | EDT | 6:21 a.m. | 6:21 a.m.* | 12.3% | 6:28 a.m. |

| Yarmouth, NS | ADT | 5:42 a.m. | 6:33 a.m. | 78.6% | 7:33 a.m. |

The eclipse will also be visible from start to finish from parts of Africa and Europe, generally as a late-morning or early-afternoon event and appearing well up in the south-southeast sky. Below we provide times for some selected cities listed in Universal Time.

| Location | Eclipse starts | Maximum eclipse | Magnitude | Eclipse ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casablanca | 9:02 a.m. | 9:22 a.m. | 2.50% | 9:41 a.m. |

| Madrid | 9:01 a.m. | 9:42 a.m. | 11.20% | 10:26 a.m. |

| Paris | 9:12 a.m. | 10:11 a.m. | 23.30% | 11:14 a.m. |

| London | 9:08 a.m. | 10:12 a.m. | 30.90% | 11:21 a.m. |

| Reykjavik | 9:06 a.m. | 10:17 a.m. | 69.40% | 11:32 a.m. |

| Berlin | 9:36 a.m. | 10:38 a.m. | 23.90% | 11:42 a.m. |

| Oslo | 9:30 a.m. | 10:42 a.m. | 42.50% | 11:56 a.m. |

| Stockholm | 9:42 a.m. | 10:53 a.m. | 38.10% | 12:05 p.m. |

| Helsinki | 9:52 a.m. | 11:04 a.m. | 38.30% | 12:14 p.m. |

| Moscow | 10:22 a.m. | 11:26 a.m. | 26.50% | 12:27 p.m. |

Be careful: How to safely observe the solar eclipse

No doubt for a few hours on Thursday morning the eclipse will top the news, followed of course by the usual dire warnings to the public not to risk blindness by carelessly looking at it. This has given most people the idea that eclipses are dangerous.

Not so! It's the sun that's dangerous — all the time! Ordinarily, we have no reason to gaze at it. An eclipse gives us a reason, but we shouldn't.

There are some safe ways, however.

The only recommended safe filters — those known to block not just the visible, but also the invisible, damaging infrared and ultraviolet rays — are a rectangular arc welder's glass that dims the sun comfortably in visual light (shade #14 for a normal bright sun), or certified eclipse glasses utilizing black polymer, or a metalized filter such as Mylar all made specifically for sun viewing. On a telescope, binoculars, or camera, the filter must be attached securely over the front of the instrument, never behind the eyepiece.

The safest way to watch is by means of projecting the sun's image onto a white sheet of paper or cardboard. Poke a small hole in an index card with a pencil point and hold a second card 2 or 3 feet (0.6 to 0.9 meters) behind it. The projected image will undergo all the phases of the eclipse. A large hole makes the image bright but fuzzy; a smaller hole makes it dim but sharp. You can also enclose this setup in a box to keep out as much daylight as possible. For a nice, sharp image, some have used a tiny pinhole pierced in aluminum foil.

Related: How to safely observe the sun (infographic)

A leafy tree can form a profusion of natural pinhole projectors. Watch the dappled ground in the shadow of a tree for swarms of crescents or rings instead of the usual round sun disks.

Better yet, make use of a "pinhole mirror" by covering a pocket mirror with a piece of paper that has a 0.25-inch (0.6 centimeters) hole punched in it, and then reflect a spot of sunlight onto a nearby wall. The image will be 1 inch (2.54 cm) across for every 9 feet (2.7 m) from the mirror. Of course, don't let anyone look at the sun in the mirror!

Telescopes and binoculars can project a much larger, sharper and brighter image of the sun, which can also show any sunspot groups that may be present. Just be sure no one looks at the sun through the instrument!

Good luck and clear skies.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing solar eclipse photo and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.