The Problems with the Cosmic Calendar

Very important things have happened very quickly.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University, host of Ask a Spaceman and Space Radio, and author of "Your Place in the Universe." Sutter contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

OK, it's been a while since I've had a nice, long rant. I'm in the mood, and you're in for a real treat. Have you ever heard of the so-called cosmic calendar? This is a frequently used device to illustrate just how small and insignificant and inconsequential our lives here on Earth are in the grand scheme of things.

Now, don't get me wrong — our lives here on Earth are small and insignificant and inconsequential … but only in a certain frame of reference, and that certain frame of reference doesn't necessarily apply to cosmic scales.

Related: The Universe: Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps

Save the date

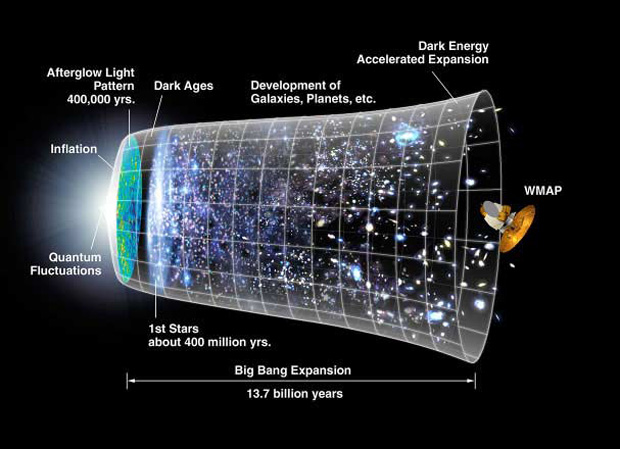

The cosmic calendar compresses the entire history of the universe — all 13 and change billion years of it — into a single calendar year. You know, one orbit of the Earth around the sun. It starts with the earliest moments of the Big Bang on Jan. 1 and continues on through the evolution of stars and galaxies through spring and summer. In this calendar, you'll find that life didn't arise on Earth until late fall, and that humanity didn't become humanity until almost the new year.

As scary as this sounds, it is entirely accurate. On this sort of scale, humans are — like I said — small and insignificant.

But that's not the only scale available for us to judge importance in the universe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sure, on billions-of-years cosmic time scales, humans haven't been around for very long. We just haven't had enough time. But this construction ignores some of the most momentous events to ever occur in the entire history of the universe, completely sweeping them under the rug simply because they happened so quickly. And just because something happens quickly doesn't mean it's not important.

I'm talking about some of the earliest moments of the Big Bang. Events that were so important and so impactful that they completely altered the course of cosmic history — and yet they were over in less time than it will take you to finish reading this article.

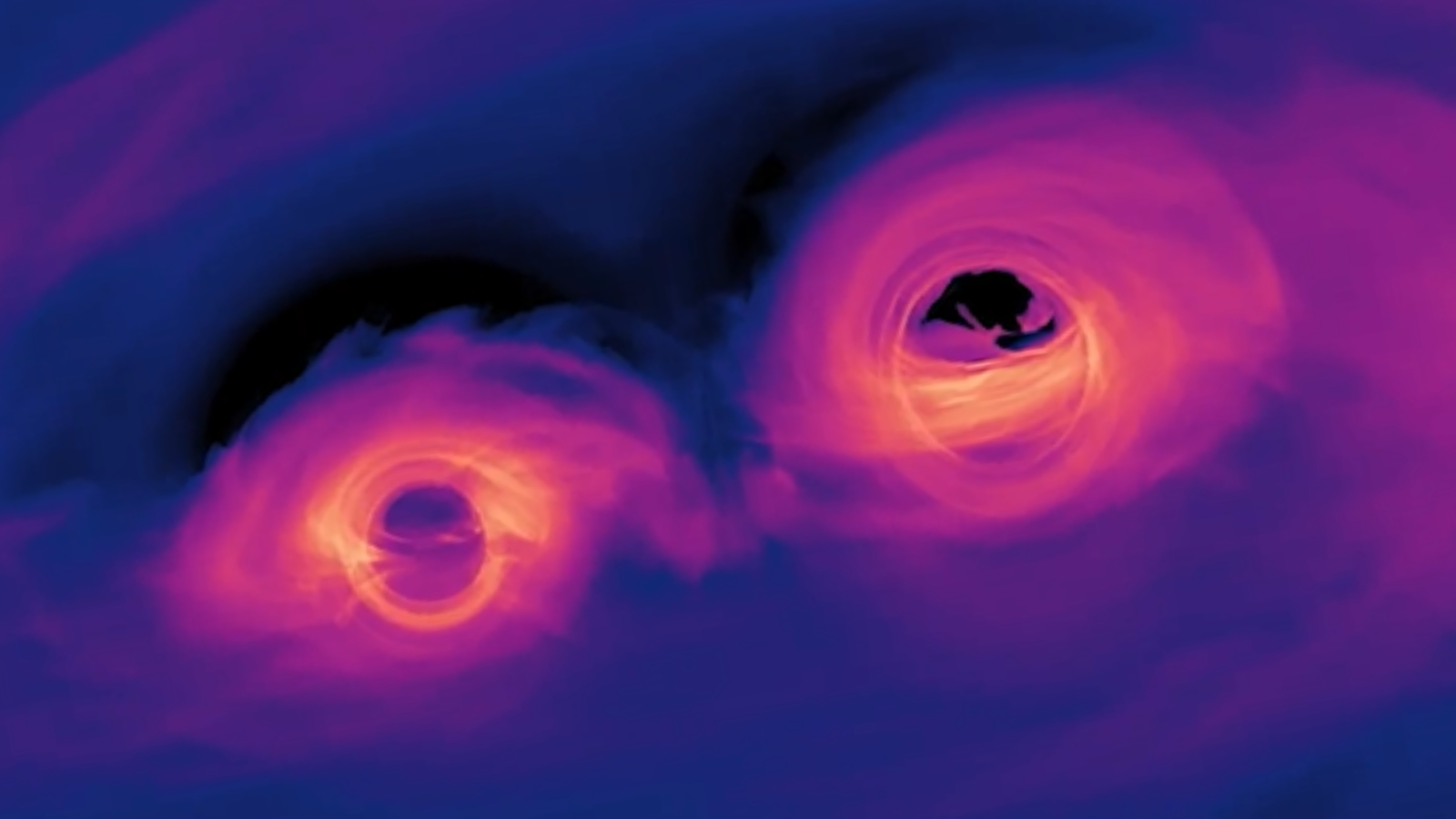

Quick and deadly

Take, for example, the event known as cosmic inflation. When the universe was a mere a billionth of a billionth of a billionth of a billionth of a second old, it rapidly expanded many times over. In a blink of a blink of a blink of an eye, it grew to over 50 times its previous radius. On the cosmic calendar, you can't even write down the words for inflation — they don't fit. And yet this event single-handedly changed the universe forever. It laid down the seeds of later structures (you know, stars and galaxies and you and me), it completely emptied out the universe of strange defects left over from an even earlier epoch, and it filled the universe with the matter and radiation that we know and love today. Our universe would simply be unrecognizable without this event, and yet the cosmic calendar has no room for it.

Or take nucleosynthesis. This is the fancy word for the formation of elements in the early universe. When our cosmos was just 10 to 20 minutes old, it formed all of the available hydrogen and helium and a tiny little bit of lithium that continues to fill the universe today. One or two dozen minutes, and all the raw material needed to build stars and galaxies and you and me. That's it. Compared to the tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years that humans have walked the Earth, that is absolutely nothing.

Related: How Inflation Gave the Universe the Ultimate Kick Start (Infographic)

One last flash

The first atoms formed in our universe when it was only 380,000 years old. That's when it cooled down enough for electrons to find some proton friends, start to hang out and go steady, and build a long-term relationship. That actual event (which we call recombination for various historical reasons) took place over the course of about 10,000 years. In that tiny window (compared to the vast age of our current universe), it completely transformed from a hot dense plasma into a neutral gas that would eventually evolve into — you guessed it — stars and galaxies and planets and you and me.

Humans have been around on the Earth for a couple hundred thousand years or so, and we've been writing things down for at least 6,000 years. And if those numbers are insignificant on cosmic timescales, must the same be argued for the formation of atoms?

Ultimately, the cosmic calendar is still biased toward our humanity, despite its attempts to show us how insignificant we are on cosmic scales. It's still based on our calendar and our ways of dividing up the year. But those kinds of divisions only make sense to us humans here on Earth. The universe simply does its own thing. And yes, most of those things are achingly slow processes. But some of them are blindingly fast and arguably much more important than the later, slower stages in cosmic evolution.

If you're ever tempted to think that humans don't matter because of the cosmic calendar, remember this: Your heartbeat lasts about one second, and in the first second in the history of our universe, more things, and more momentous things, happened than would ever occur in the eons after.

- The Big Bang: What Really Happened at Our Universe's Birth?

- Why We Need Cosmic Inflation

- The Universe's Dark Ages: How Our Cosmos Survived

Learn more by listening to the episode "What's wrong with the cosmic calendar?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to Okie J. for the questions that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.