A neutron-star crash spotted 3 years ago is still pumping out X-rays. But why?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

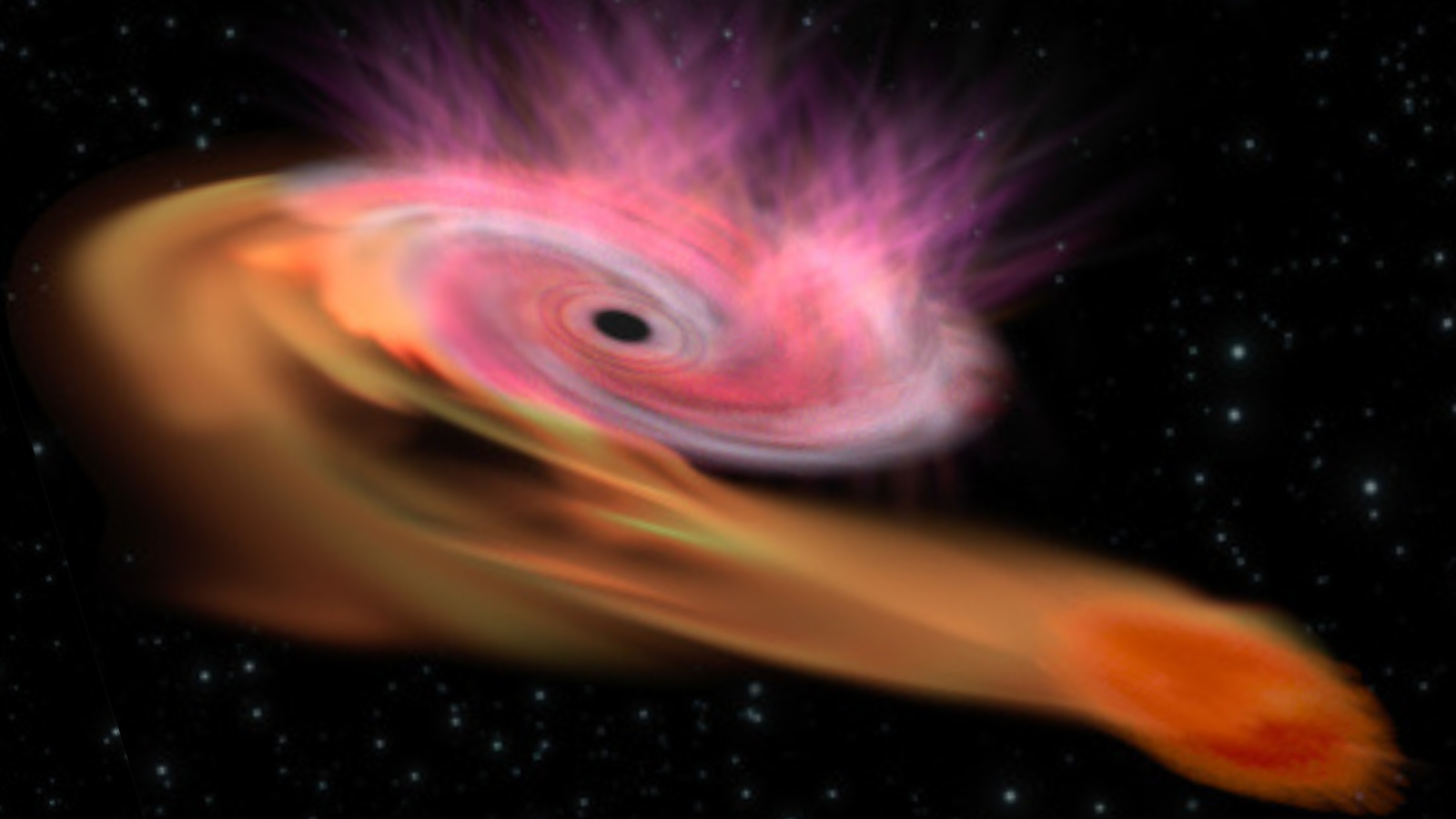

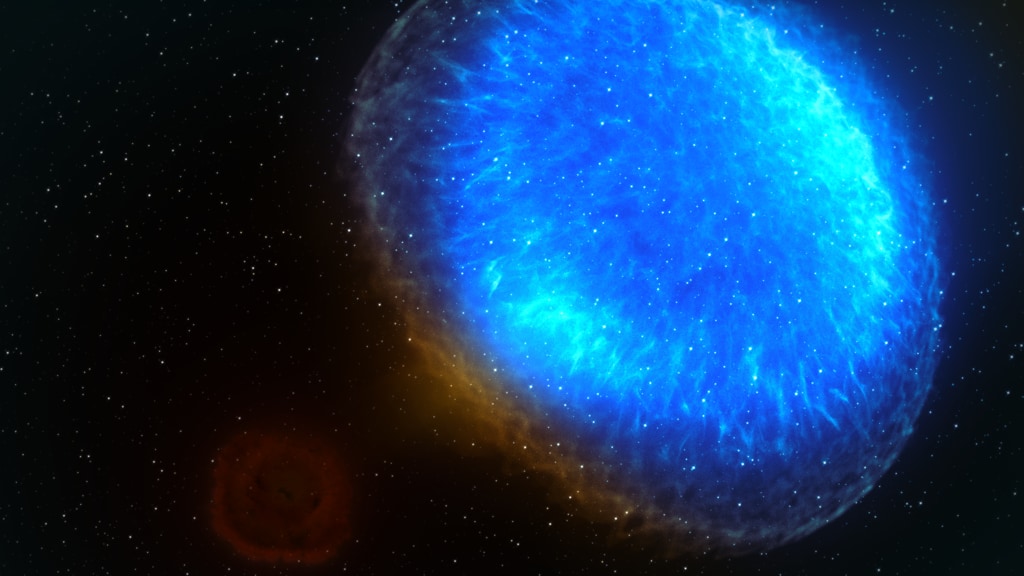

Three years ago, two neutron stars collided in a cataclysmic crash, the first such merger ever observed directly. Naturally, scientists kept their eye on it — and now, something strange is happening.

Astrophysicists observed the star collision on Aug. 17, 2017, spotting for the first time ever signs of the same event in both a gravitational-wave chirp detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) on Earth and a massive burst of different flavors of light. The X-rays observed at the location 130 million light-years from Earth peaked less than six months after the merger's discovery, then began to fade. But in observations gathered this year, that trend has stopped, and an X-ray signal is unexpectedly lingering, according to research presented on Thursday (Jan. 14) at the 237th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, held virtually due to the pandemic.

"Our models so far were describing the observation incredibly well, so we thought we nailed it down," Eleonora Troja, an astrophysicist at the University of Maryland and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, told Space.com. "I think everybody was convinced that this thing was going to fade quickly, and the last observation showed that it is not."

In images: An amazing neutron-star crash discovery, gravitational waves & more

A star crash checkup … and mystery

When NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory checked in on the former merger in the spring, things were beginning to look fishy. Scientists thought they were looking at the afterglow of the high-energy jet of material shot out by the collision, and they had expected the X-rays to have faded by the spring. But the source was still glowing in the spacecraft's view. When the telescope looked again, in December, it still found a bright X-ray signal.

It's too early to know what precisely is happening, Troja said. Chandra may not look again until this December, although she plans to ask for the telescope to change plans to check in sooner. Radio instruments can study the collision more frequently, and could help solve the puzzle between now and then.

For now, Troja believes one of two hypotheses will explain the continued X-ray emissions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In one scenario, the lingering X-rays are joined by radio light within the next eight months or year. Troja said that would suggest that scientists are seeing not the afterglow of jets shooting out from the collision, but the afterglow of the massive kilonova explosion itself — something scientists have never seen before.

"People think that in the 21st century we have seen it all and there is no first time left," she said. Not so if this hypothesis holds. "This would be a first, it would be a new type of light, a new form of astrophysical source that we have never seen before."

If the X-ray emissions continue but no radio emissions join them, Troja thinks scientists may be looking at something perhaps still more intriguing: proof that the collision formed a massive neutron star, the most massive such object known to date.

Soon after the collision, scientists calculated the mass of the initial neutron stars and the mass of what was left, after the dramatics shot matter out into space. But that value is between the current largest known neutron star and the smallest known black hole, leaving scientists stumped. The new observations could decide it: If the object is emitting X-rays, it sure isn't a black hole. Confirming the result of the collision would give scientists an opportunity to better understand how matter behaves in superdense neutron stars, she said.

"We have a beautiful problem," Troja said. "No matter what the solution is, it's going to be exciting, which is a great problem to have in astrophysics."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.