This ISS mission could 'open some eyes' about climate science

"Wherever we need chemistry to understand something on the surface, we can do that with imaging spectroscopy. Now, with EMIT, we're going to see the big picture, and that’s certainly going to open some eyes."

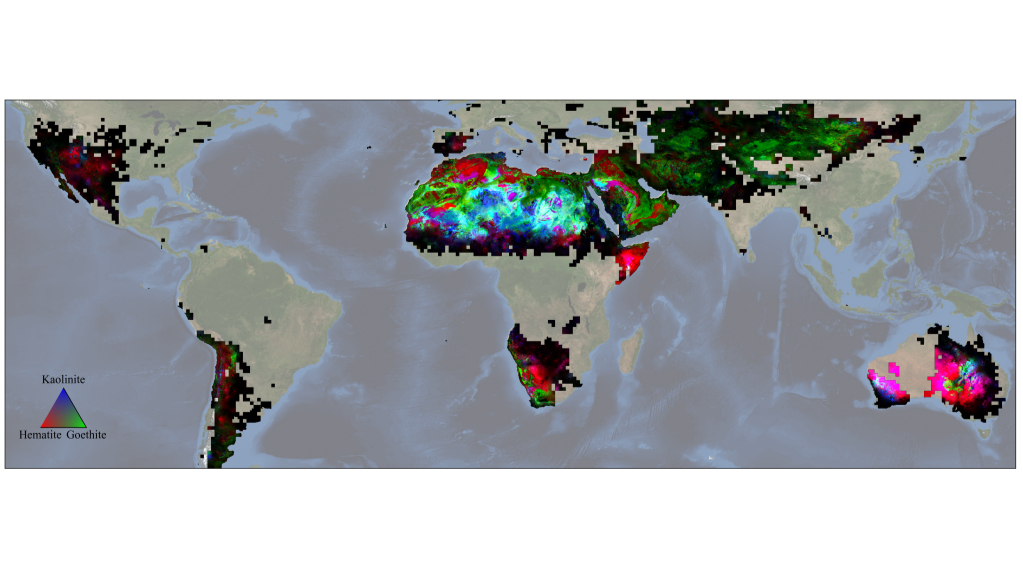

NASA's Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) mission has delivered the first-ever comprehensive map of minerals located across Earth's dust source regions.

Created with data collected up until Nov. 2023 by an imaging spectrometer based on the International Space Station (ISS), shows the precise locations of 10 important minerals based on how they reflect and absorb light.

As wind currents pick up particles of these minerals and distribute them across the globe, the particles can either absorb or reflect light based on how light in color they are. Thus, such minerals can have a climate effect by either cooling or warming the atmosphere. What this means is the new EMIT map could deliver a better picture of mineral distribution across Earth, help scientists better understand the abundance of these particles, and ultimately find if they have a net cooling or warming effect. In turn, this would lead to better climate models — something quite necessary as the human-driven climate crisis continues to worsen.

"Wherever we need chemistry to understand something on the surface, we can do that with imaging spectroscopy," Roger Clark, an EMIT science team member and Planetary Science Institute researcher, said in a statement. "Now, with EMIT, we're going to see the big picture, and that’s certainly going to open some eyes."

Related: ‘Failed star’ is the coldest radio wave source ever discovered

EMIT was developed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and reached the ISS in 2022. Since August of that year, the spectrometer has been studying Earth's surface from an altitude of around about 250 miles (410 kilometers).

'Big picture' climate science

EMIT's low-Earth orbit vantage point lets the system analyze areas of our planet that ground-based geologists wouldn’t have a chance of reaching. In fact, it can even dissect some regions that wouldn’t even be accessible to instruments carried by aircraft — all while delivering the same kind of detail possible with close-quarters, Earth-based investigations.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During its approximately 17 months of operation, EMIT captured around 55,000 50-by-50-mile (80-by-80-kilometer) images of Earth across a targeted area of study. Composed of billions of measurements, these include "scenes" of a 6,900-mile-wide (11,000-kilometer-wide) belt across our planet's midsection that hosts dusty, arid regions.

In addition to creating detailed maps of the surface composition of these chosen regions, EMIT has also been able to detect plumes of greenhouse gases, like methane and carbon dioxide, that emerge from Earth-based regions like landfills, oil facilities and other human-made infrastructure.

Through investigations like this, EMIT will give scientists an idea of how dust particles travel around Earth's atmosphere, where they come from, and in what amounts. This will aid in determining their colors and whether they are reflecting or absorbing light more strongly. Data like this has been available to scientists before, but it came from only around 5,000 sites; EMIT offers billions of samples and in much greater detail.

"We'll take the new maps and put them into our climate models, and from that, we'll know what fraction of aerosols are absorbing heat versus reflecting to a much greater extent than we have known in the past," Natalie Mahowald, a scientist at Cornell University scientist EMIT's deputy principal investigator, said in the statement.

Measuring ecosystem impacts

EMIT will have a scientific impact in fields beyond climate, too.

The data it collects from the ISS, scientists say, can be used to analyze the impact that dust carried by winds has on the ecosystems in which it lands. This is important because there is evidence that when particles land in the ocean, it encourages the growth of phytoplankton blooms. These accumulations of microscopic algae can be beneficial in some ways, but can also be responsible for toxins that accumulate in ocean ecosystems. These toxins harm marine species, and eventually via the food chain, humans.

This wind-swept dust can also have positive impacts. For instance, when dust from the Andes of South America lands in northern and sub-Saharan Africa, it can bring with it nutrients needed for rainforest growth in the Amazon Basin. Using EMIT data, scientists can track the distribution of vital elements for this fertilization process, like phosphorus, calcium and potassium.

"EMIT could help us to build more intricate and finely resolved dust-transport models to track the movement of those nutrients across long distances," Eric Slessarev, a soil scientist at Yale University, said in the statement. "That will help us to better understand the chemistry of soils in places very far from the dust-generating regions."

EMIT data can also be used to identify vegetation, snow and ice as well as human-created materials on and above Earth's surface.

"To this point, we simply haven’t known the distribution of surface minerals over huge swaths of the planet. There will likely be a new generation of science that comes out that we don’t know about yet, and that’s a really cool thing," mineral map pioneer and JPL data scientist Phil Brodrick added.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.